Word Music: Composing Using Text Scores, with Maya Shenfeld

Whether you’re an electronic producer, a pop musician or a classical composer, you likely have at some point found yourself feeling hemmed in by the impression that there are some intangible rules that music-makers must follow. We might feel that we should try and fit into a certain role; that to be a producer we must meet others’ expectations; or that the performer is this and the composer that, and the audience is neither of these things. For our creative processes, these supposed norms can be more of a hindrance than a help. We can find ourselves gripped by the fear of making a ‘wrong’ move, musically, creatively, or even relationally, as a composer, a performer or a producer.

Luckily, there are tools that can break us out of this mindset, and help us rediscover joy, spontaneity and inspiration in the creative process, especially when collaborating with other music makers. At Loop Create 2022, composer, performer and educator Maya Shenfeld joined us to share the liberating experience of using text scores when writing and performing music. During Shenfeld’s workshop, Loop attendees were invited to write their own text scores, then share and perform them.

Here you can find Shenfeld’s overview of the history of text scores, as well as some ideas for how to use them in your own practice.

Text scores can be any type of instruction, concept, action, or idea for a musical piece that is written down in words. These scores simply convey an idea that the composer would like the performers to think about, or perhaps an action they would like the performers to follow.

If you’d prefer to get your hands dirty right away, you can dive into a collection of text scores from the workshop, all shared on the day by Loop attendees.

Fluxus

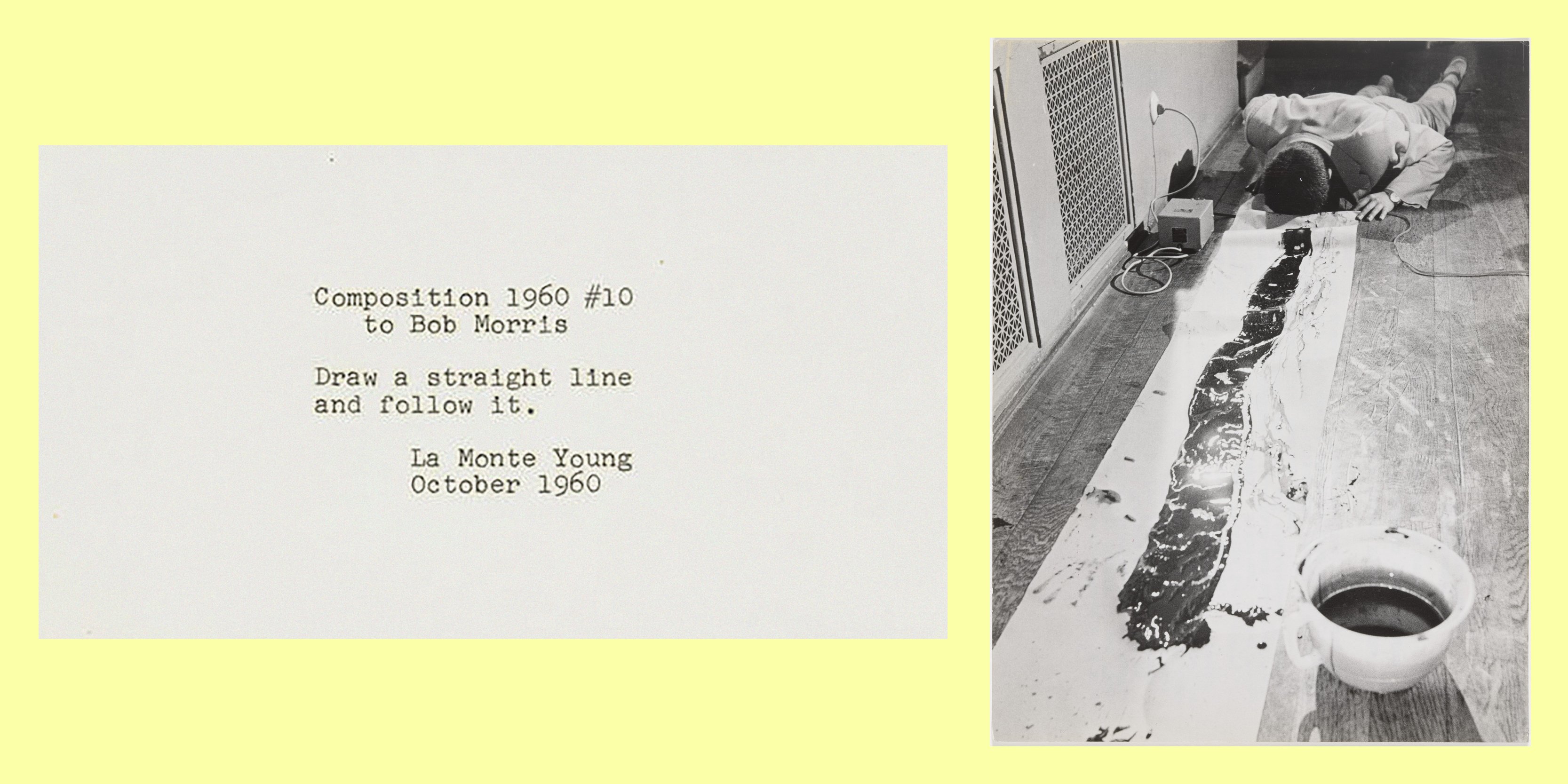

At the first Fluxus Festival in 1962 in Wiesbaden, composer and artist Nam June Paik staged a performance of La Monte Young’s “Composition 1960 #10.”

A bemused audience watches as Paik dips first his tie, and then his hair, into a bucket of paint, to draw and follow a straight line, as per Young’s score.

Left: La Monte Young ‘Composition 1960 #10’,1960. Image courtesy of Whitney Museum Of American Art. Right: Nam June Paik performing La Monte Young's Composition 1960 #10 (to Bob Morris) during Fluxus Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik, Städtisches Museum, Wiesbaden, September 1–23, 1962. Image courtesy of MoMA.

Is this music? Is this a score? Neither? Both? Who’s to say?

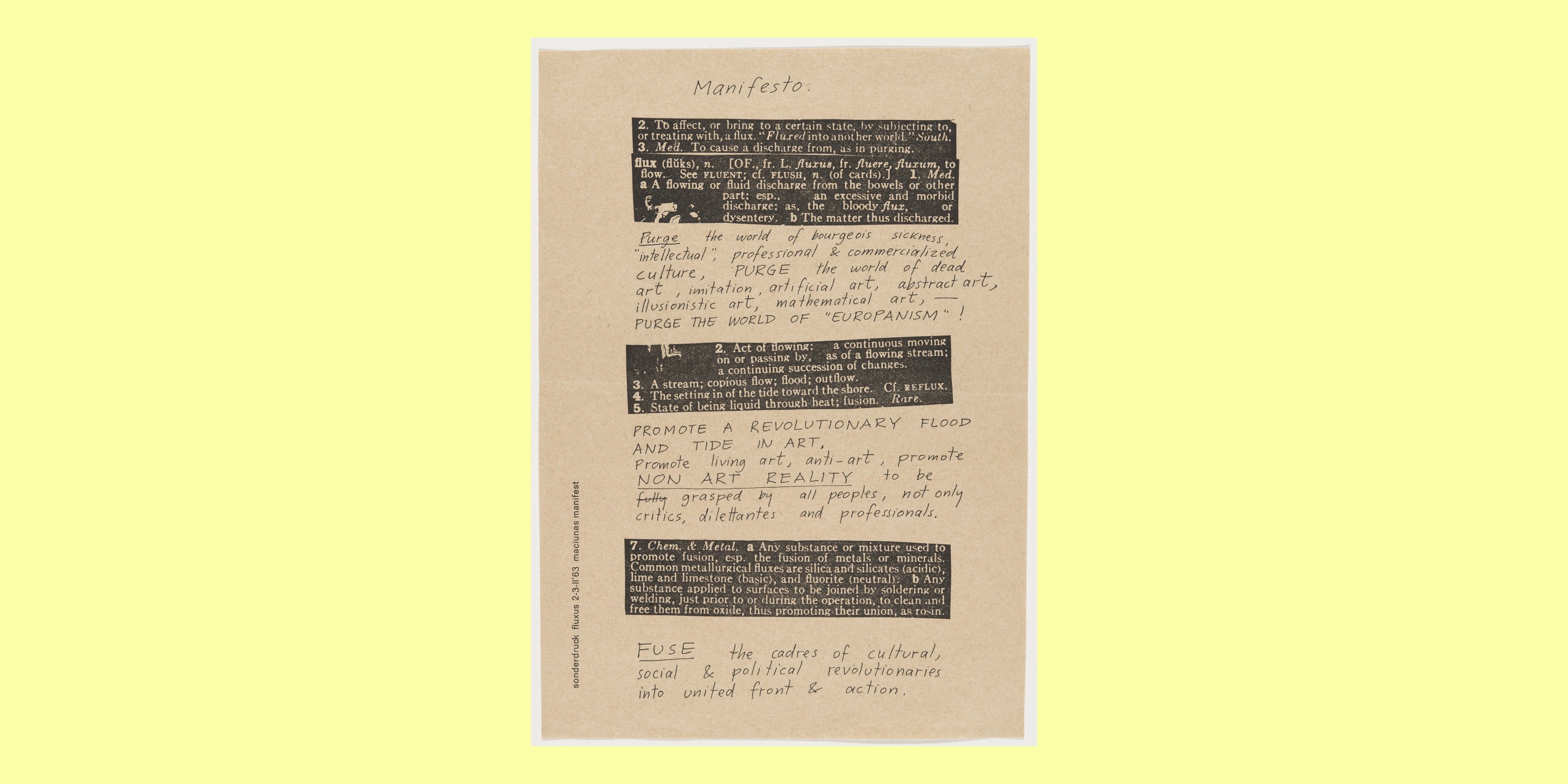

Both Paik and Young were artists from the 1960s Fluxus movement. They participated in its ‘happenings’; multi-media performances that aimed to blur the distinctions between art, music and everyday life. For Fluxus artists, the problems of society were mirrored in the hierarchies of art and music-making; in the traditional roles proscribed to the composer vs the performer, the performer vs the audience, the artist vs the critic. George Manciunas’ 1963 Fluxus Manifesto states that one of the movement’s aims is to “promote living art, anti-art, promote NON ART REALITY to be fully grasped by all peoples, not only critics, dilettantes and professionals.”

George Maciunas ‘Fluxus Manifesto’, 1963. Courtesy of MoMA.

Fluxus composers sought to create music that everyone could compose and play, regardless of their level of musical training. Starting with George Brecht, many Fluxus artists preferred to write the instructions for their works in words, on little cards, rather than using formal musical notation. In doing so, they created situations or scenes that could be interpreted by any performer in many ways, and thereby kicked off a tradition of text score writing that continues on into the present day.

What are text scores?

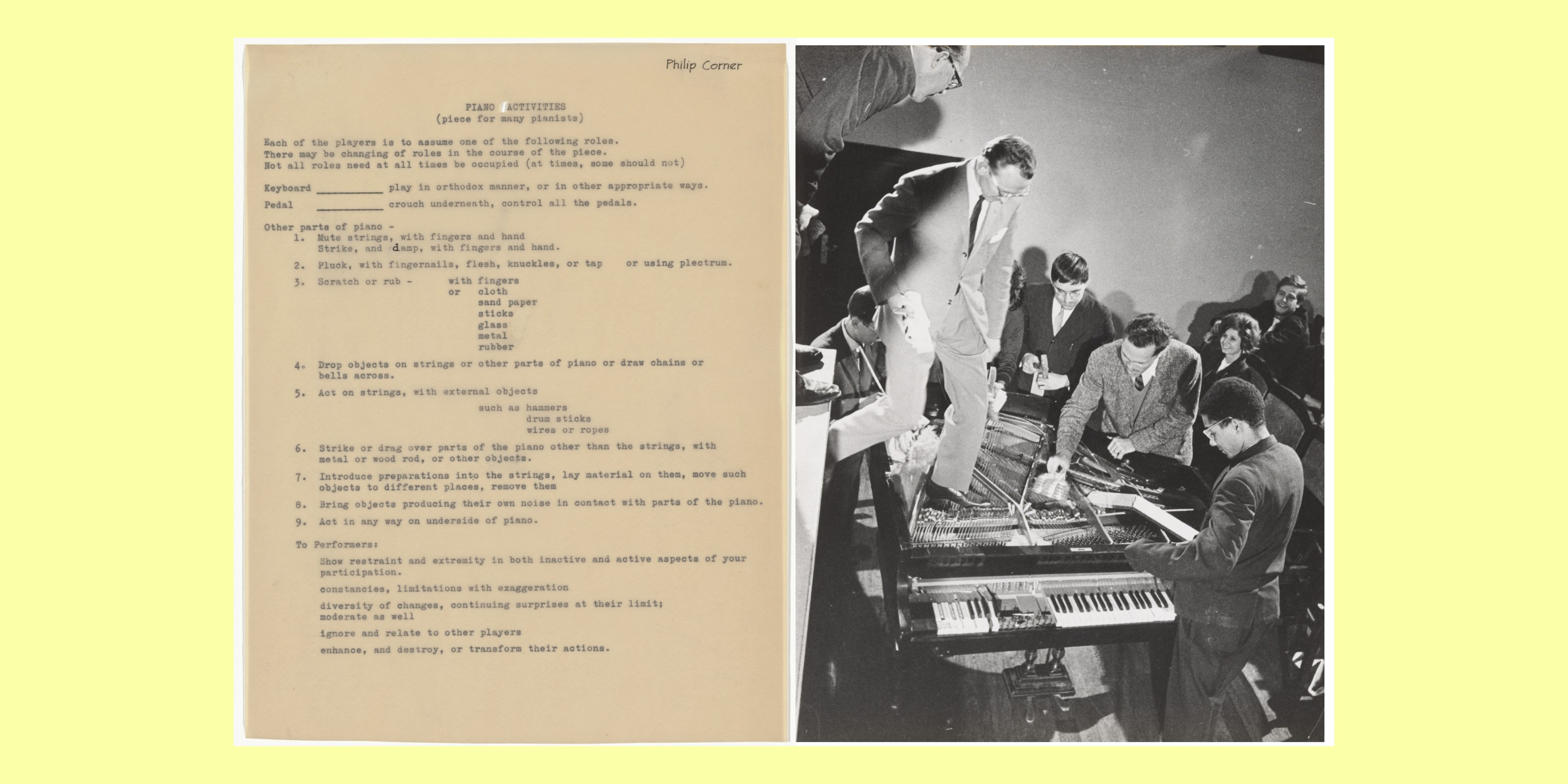

Text scores can be as simple as the above example by La Monte Young; others are much more complex. For example, “Piano Activities” by Philip Corner spans three pages with step-by-step instructions for the performers to follow.

Left: Score of Piano Activities by Philip Corner 1962. Right: Philip Corner's Piano Activities, performed by Philip Corner, George Maciunas, Emmett Williams, Benjamin Patterson, Dick Higgins, and Alison Knowles during Fluxus Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik, Hörsaal des Städtischen Museums, Wiesbaden, Germany, September 1, 1962. Images courtesy of MoMA.

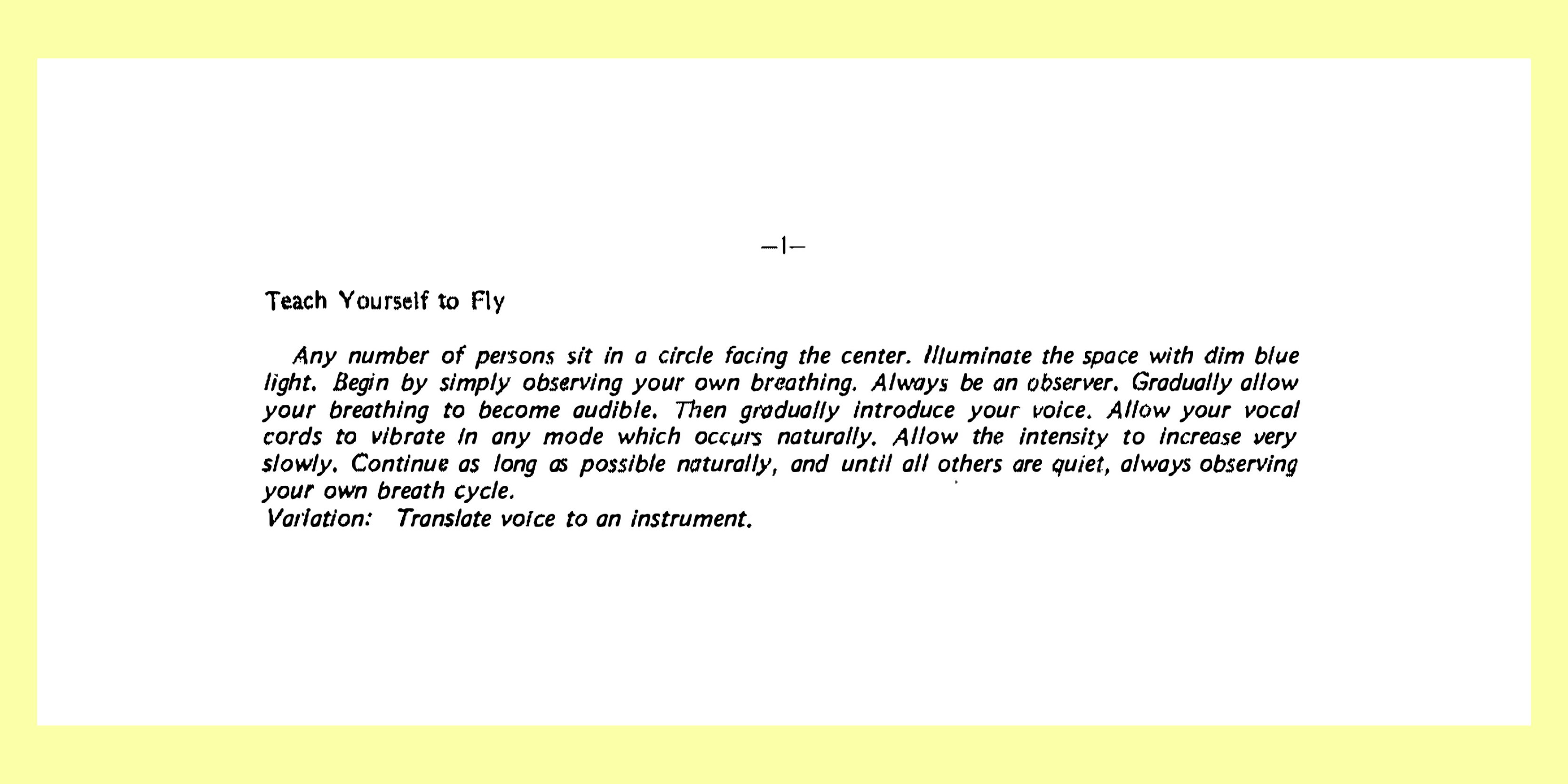

While the concept of text scores as composition medium originated in the 1960s, the opportunities they offer for interpretation and collaboration have continued to inspire composers across genres and decades. Renowned electronic music pioneer Pauline Oliveros has acknowledged Fluxus as a major influence on her more experimental works, and expanded on the concept of the text score with her book of Sonic Meditations I – XXV (1971), described as “a collection of verbally notated meditations that may be enjoyed by anyone in a variety of ways: read as poetry, performed alone or performed for an audience.”

“Teach Yourself to Fly” from Sonic Meditations, by Pauline Oliveros. Copyright Smith Publications, Sharon, Vermont. Used by permission.

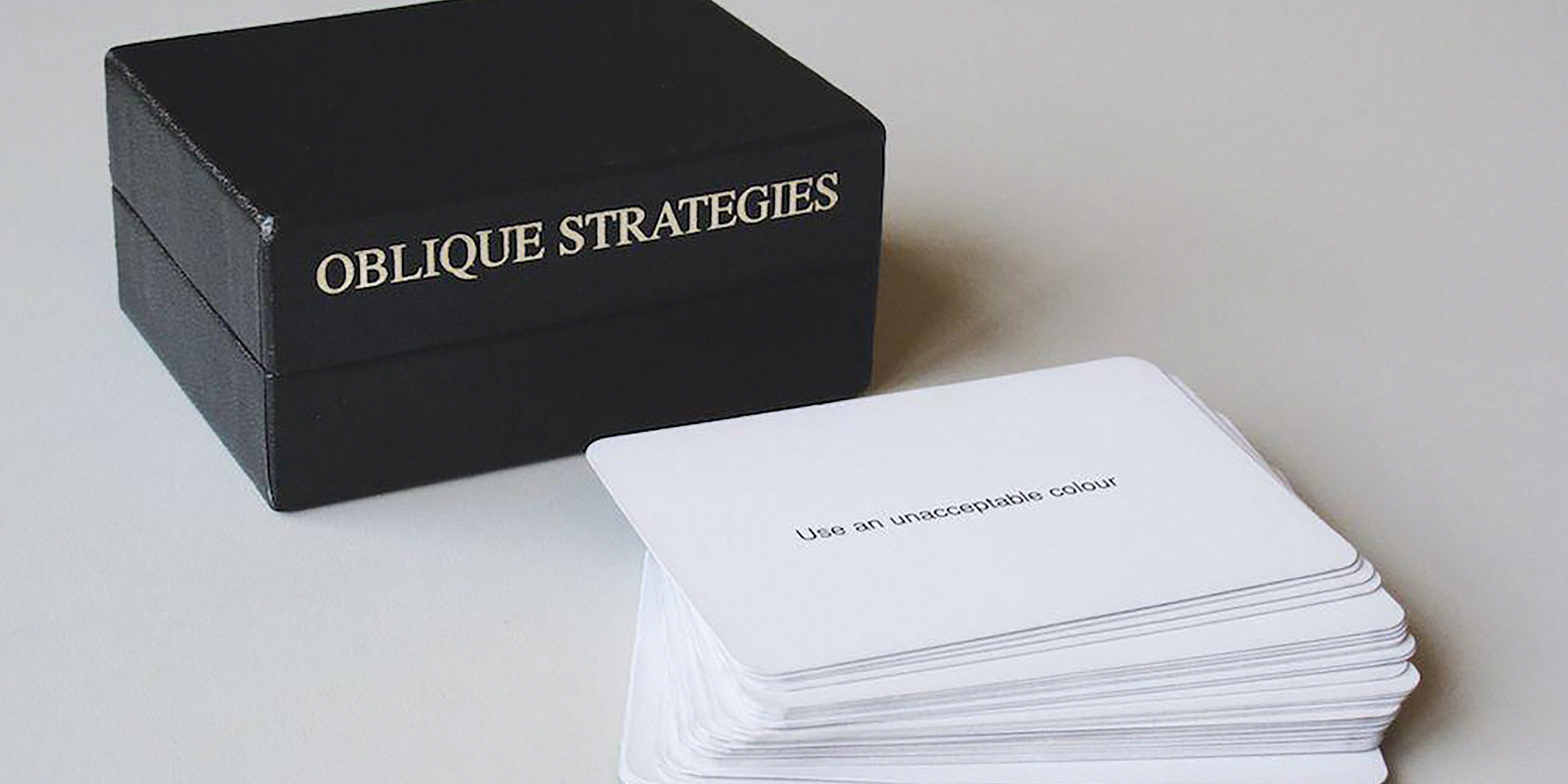

Another example of this tradition can be found in Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt’s “Oblique Strategies” deck; a collection of 115 simple, white cards featuring short instructions, intended to be drawn upon at random by creators or artists faced with any kind of creative block. This deck remains in popular usage today, and a digital version can be accessed for free online.

Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies deck.

Also in the tradition of Fluxus, contemporary Irish composer Jennifer Walshe is inspired by the possibilities offered by text scores to break down hierarchies and allow musicians to step beyond their preordained roles, particularly the classical world. In “The New Discipline Manifesto” of 2016, she presents an approach that “is located in the fact of composers being interested and willing to perform, to get their hands dirty, to do it themselves, to do it immediately.”

Her avid love for text scores has been combined with the much more recent technologies of data sets and neural networks for her 2021 collection The Text Score Dataset 1.0, where she fed a vast archive of text scores into a neural network and generated a collection of scores as evocative and exciting as any from past composers.

The Text Score Dataset 1.0, Jennifer Walshe, 2021, Darmstädter Ferienkurse.

Following text scores

In preparation for Loop Create, Shenfeld invited a small ensemble of musicians to the Ableton studio to experiment with following and performing text scores. Producer and vocalist Lani Bagley and composer and double bass player Caleb Salgado joined Shenfeld to perform a number of different works, and spend time reflecting on their experiences of doing so.

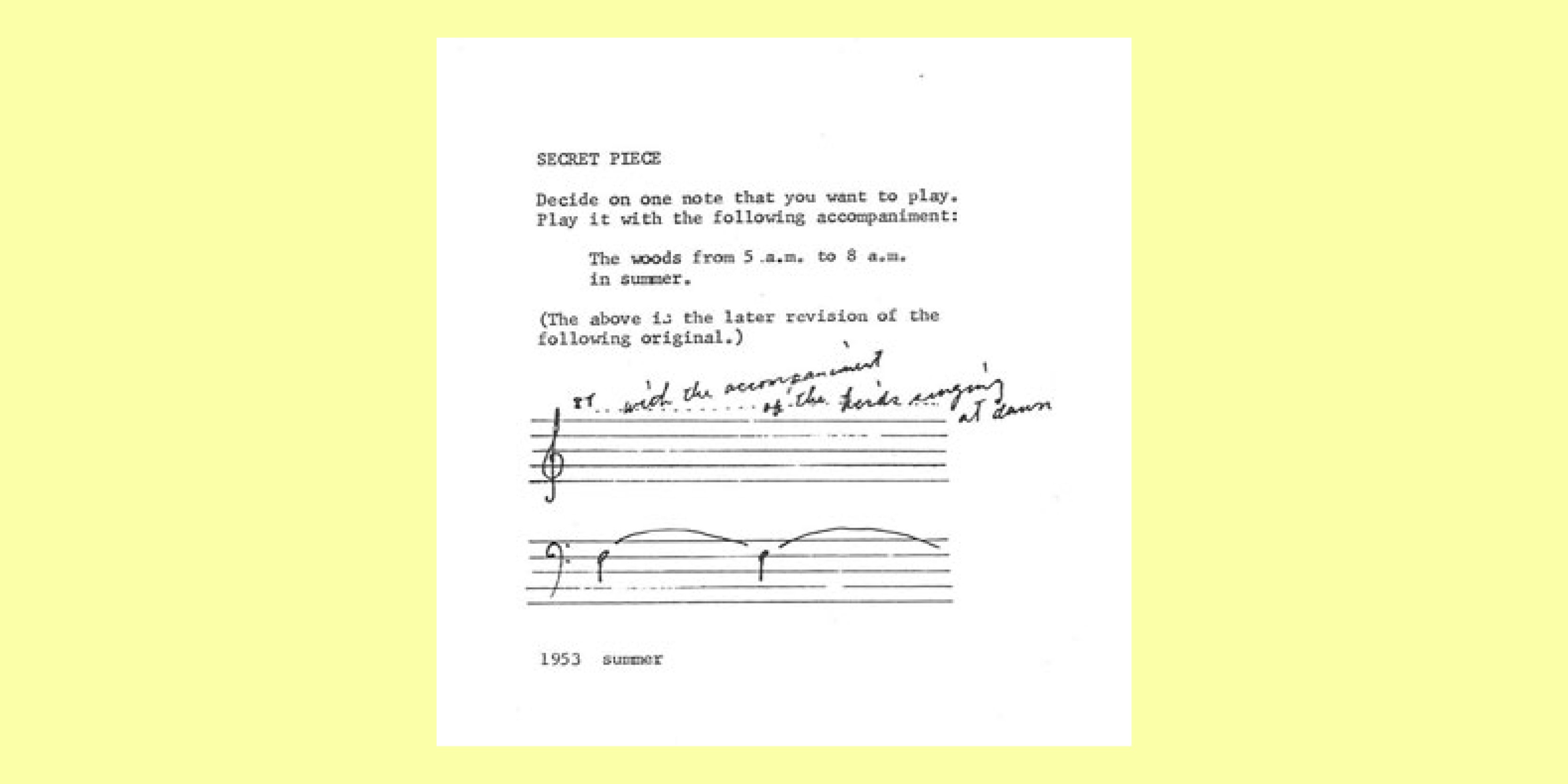

Perhaps the most well-known composer of Fluxus, Yoko Ono created and used text scores prolifically. Many of her works can be found in her 1964 book Grapefruit. One of these works, “Secret Piece”, was composed in response to a prompt at music school, in which the students were requested to transcribe, in traditional notation, the soundscape of their environment.

Yoko Ono. “Secret Piece,” from Grapefruit. 1964. Artist’s book (Tokyo: Wunternaum Press).

On the lower part of the score we see an early version of the piece, in which Ono began working using traditional notation. The bass clef holds a single, sustained note, but the treble clef offering empty – this is where Oko gave up on using traditional notation, instead simply including the written instruction “with the accompaniment of the birds at dawn.” The text at the top of the page is the later version of the piece.

These instructions are both specific (there is a time of year and a time of day specified), and general (must it be performed at between 5am and 8am, or do we just need the sounds of the birds at dawn? Should the note be sustained, repeated, or played once?). Rather than attempting a performance in the woods at daybreak, Shenfeld’s ensemble opted to perform instead with the accompaniment of a recording of the woods at dawn, then discussed their other decisions throughout the session.

As we can see from the conversation amongst Shenfeld’s ensemble, there is no ‘correct’ way to interpret this score. After discussion and reflection, their second performance yielded vastly different results. Performances by other ensembles will also differ greatly from one to another, as evidenced by an interpretation of the same piece by experimental hip hop trio clipping.

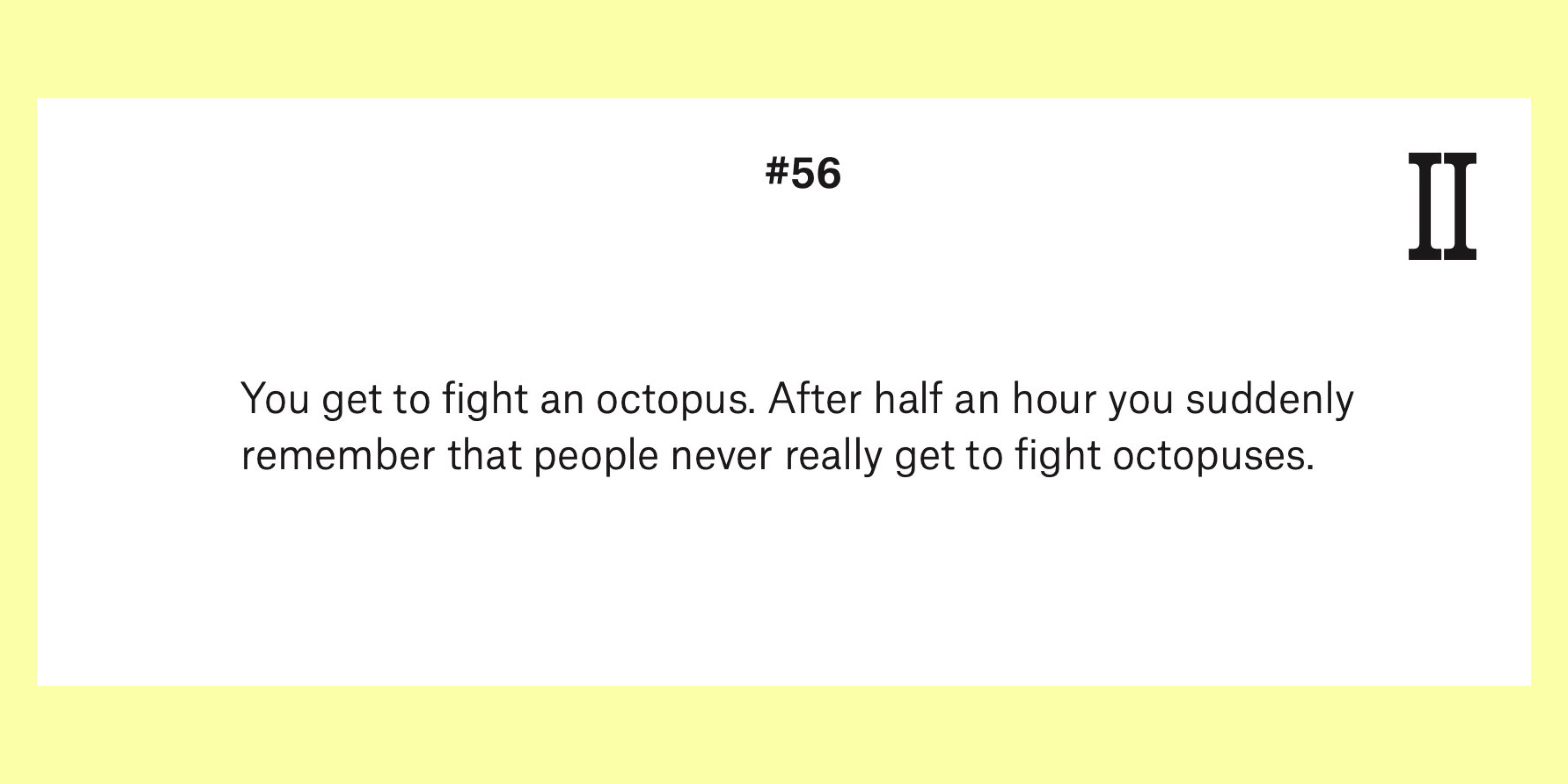

Wanting to perform a more contemporary example with her ensemble, Shenfeld also selected a work from Jennifer Walshe’s neural-network-generated collection “The Text Score Dataset 1.0.”

Fight An Octopus score from The Text Score Dataset 1.0, Jennifer Walshe, 2021, Darmstädter Ferienkurse.

The ensemble took two different approaches to performing this work. In their first performance, the group read the score aloud and embarked on the performance without any discussion of what their collective approach would be. We then watch them reflecting on that experience prior to their second performance, aligning their intentions and their approach, resulting in a vastly different experience. As there is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ way to perform a text score, any performer or group of performers can take any approach they feel inspired to, as the performance is intended to be as different as every musician performing the work.

Making and using your own text scores

While the vast historical and contemporary archive of text scores is rich and rewarding to draw upon, it’s not necessary to look to the work of others to experience the joy of performing with text scores. In the tradition of Fluxus and The New Discipline, we can just as easily “get our hands dirty” – do it ourselves, and do it immediately.

All you need to do is write down an instruction, and then follow it. The instruction could be something poetic, or it could be a practical action, but ideally it should be something that causes you to step outside of your habitual music-making practices and encourages you to start thinking (and playing) in a new way.

While they’re effective in solo-music-making settings, as we can see from Shenfeld’s experiences with her ensemble, text scores also make for a powerful collaboration tool. Whether a score is chosen from the wealth of text scores already in the world, or written afresh for a new project, inviting an ensemble to interpret it together can disrupt pre-existing hierarchies or preconceptions within a collaborative group. A text score can also provide a group with a starting point to generate new material, or develop existing material, in a spontaneous and unexpected way.

Text scores aren’t only for use in performances, or longer, durational music-making experiences – they’re also an excellent way to kickstart a session and get the creative juices flowing. At Loop Create we invited our attendees to write and perform a text score in only 20 minutes, and then to share the results.

Across the decades, artists have shown that the possibilities offered by text scores are endless. They can be used as a solo music-making tool, to break through creative blocks and to generate new ideas. They can be used within a group to start an improvisation or a collaboration. And they can be used to encourage collaborators to step beyond their perceived roles and have fun with experimentation and play. Despite their simplicity, text scores never yield the same result twice, and in many respects have become an artform unto themselves. Why not try this yourself, and use the Loop Create 2022 text scores deck to start your next session, or even write your own text score. Share your text scores, and the music you make following them, with music makers over on the Text Scores Channel on the Loop Server on Discord*.

Text by Ivy Rossiter

Follow Maya Shenfeld on her website, Bandcamp and Instagram

*Legal note: Using Discord is subject to the terms and conditions and the privacy policy of Discord only.