Takashi Okamoto: Workflow Tips for Speed and Creativity

We’re pretty sure that, at least at one point, you’ve thought to yourself, “I wish I could finish this track faster!” Whether you’re up against a deadline with a project, or just working on music at your own pace, it never feels good to leave a track unfinished. And working on several tracks simultaneously makes the situation even more complicated; you need to use your time efficiently and switch up your mindset for each different track. So, how do production houses create so much music at such a great speed?

“I don’t use project templates but [instead] use Racks to streamline my work while maintaining a sense of originality,” says Takashi Okamoto, an Ableton Certified Trainer and video game sound designer. Okamoto has known firsthand the importance of working efficiently ever since he started his career as a sound designer at a video game venture company in the Kansai region of Japan in 2004. Here, he was not just in charge of music production, but also involved in the game product planning, developing a sales perspective in addition to expanding his creativity. The experience and knowledge he gained here gave him the opportunity to become an independent music producer and sound designer under the name 12sound, and since 2009 he has been in charge of the music for a number of high-profile games, including Obakeidoro, Cytus II, Re:Zero -Starting Life in Another World- The Prophecy of the Throne and Five Brides Puzzles. His work has showcased his versatile talents and ability to compose in a number of different musical styles; from elegant orchestral compositions, piercing electronica, cinematic ambient soundscapes, and playful sound effects.

We were very curious to find out more about the studio and production processes of a sound designer at the forefront of the industry, and how he manages to stay on top of a large number of production requests requiring a very fast turnaround. We managed to persuade Okamoto to take some time out of his busy schedule to talk with us over Zoom about a variety of topics, including his process of taking a track from start to completion, how he uses Racks to balance creativity and efficiency, and how he listens to other artists’ music to avoid running out of ideas. He was also kind enough to create some downloadable Racks that help streamline the sound creation process. Find out how to use them in the interview and experience the ingenuity of the Racks firsthand.

Download free Racks created by Takashi Okamoto*

*Requires Live 11 Suite to make full use of all the functions.

*In order to play the demo track in full, you will need the Madder Beatz and Guitars and Bass packs.

The Path of a Video Game Sound Designer Past and Present

Did your production process change from when you were working for a company to after you became independent?

My production has changed and evolved a lot, but that’s more to do with developments over the years, rather than a result of my employment situation. When I first entered the industry in 2004, it was the era when the PS2 and Nintendo DS were the mainstream home video game consoles. The specifications and memory capabilities at the time weren’t so high, and the consoles had pretty simple built-in soundcards. One game console had a 48-voice sampler with 2MB of memory, mostly with piano sounds, and I had to compose for that. It was like making a patch on a vintage Akai sampler, and you’d use MIDI to play it. So, companies needed in-house specialists with the right equipment in front of them and a basic grasp of scripting as the necessary tools to convert musical ideas into the sounds for these games. However, by the time I went independent in 2009, the PS3 and Wii were the main consoles, and they could play fully mixed and mastered tracks. This meant there was no need for companies to have in-house music technicians anymore, and in that way, the whole music production process for games had changed.

Takashi OKAMOTO feat. Tsukasa Shiraki “Cityscape" from the hit music rhythm game Cytus II

However, there has been a bit of a shakeup in the last couple of years, and I’ve started to get requests here and there to actually program the engine of the console so that the sounds are integrated into the machine. Up until recently, all I had to do was submit a WAV file, but now I have to build a development environment for the game, and I’m asked to program the sounds for a scene with a river flowing here, a waterfall there, a fire burning over that way, and so on. This is the kind of thing that game sound designers around the world are expected to do nowadays.

So currently, what does the process involve, from getting a music production request to delivering the final content?

Usually, the first thing I receive is a massive Excel file with a request for 40 tracks or whatever of a certain kind of music, with details where the music is to be used, the length of the tracks, and YouTube links to reference songs. I often get asked to start with the main theme, so I start with that, and then I do the mixdown and mastering myself, and deliver a WAV file of it. At that stage, I usually have at least a picture of the character or a description of the world within the game, but the software is not always ready to be actually played on a console. In terms of what kind of music they want, in my case, I usually like to have a thorough discussion about it with the client. If it’s an RPG with some cool guy with a sword, we’ll first talk about whether it’s set in an ancient world or a futuristic cyberspace. Will there be a lot of machinery or whatever in the game, or is it purely a world of swords and sorcery? Stuff like that. If it’s swords and sorcery, I’ll suggest making something orchestral or acoustic. If there are lots of gadgets, or the story is set in the future, I will discuss whether they want something with drums, bass, and electric guitar. I don’t think that’s the right approach every time, but players would probably be a bit baffled if they were playing a game set in a world of swords and sorcery, and there was a four-to-the-floor track with clunky synths all over it. Likewise, it wouldn’t feel right to have an old-fashioned track for a game set in the future. So, I’m thinking about things like that at this stage.

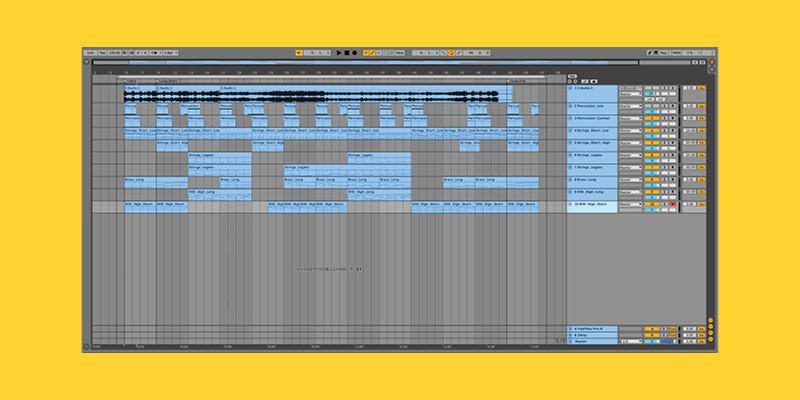

An example Takashi Okamoto Live Set. Track 1 contains a reference track from the client. To save time, the tracks remain the same color-code. The set is arranged so that percussion tracks are at the top, with parts that are more for ornamentation right down the bottom

Efficient Music Production Without Compromising Originality

How long does it take from the time of the request to delivery?

It depends on the project, but if I had to guess, I’d say roughly one track a day. In reality, I work on three or four tracks at the same time, but I ask my clients to give me four days. But that’s if I’m working on a track on my own, doing all the programming and production myself. If I have to add guitar or vocals, it’s a different story. Also, in the way I do things, I don’t really do a proper mixdown at the end. I mix and EQ things as I am adding and creating new parts and layers of sounds, so I don’t have to revisit the track later and play around with the balance of the different parts. By arranging and mixing at the same time as creating the track, I can really streamline my work process.

How do you switch between different mindsets when you are working on multiple tracks at the same time?

I feel you can train yourself to be able to do this. When you are working on something, not just music, there are times when you get a phone call, and it breaks your concentration. As a freelancer, I get work requests through Slack, Facebook messenger, and lots of other apps, and the sooner I respond to them, the better the chances of landing the job. If I take too long to reply, the job might go to someone else before I get a chance to respond. That’s why I decided to prioritize replying to e-mails and messages above anything else in my freelance work. Through doing this, I gradually learned to control my concentration so that I could get back to work immediately, no matter who or what was interrupting me during my music production flow. When I was working at a company, I couldn’t do that at all. It was like, “please not now, please not now.” But since freelancing, as I said, I want to reply as soon as possible, so I naturally became able to switch my mindset from that point, and I think that’s what helped me get to a place where I can work on multiple tracks simultaneously.

Takashi Okamoto’s studio – where Okamoto produces many tracks each day

Also, I work in parallel, so if I get stuck on one track, I can just switch over to another, and if I get stuck on that one, I can work on another different one again. This way, I can keep my ears and ideas fresh, changing up my mindset by working on something with a completely different style. When I do that, I often come up with a solution to a problem I was having with another track.

In your Certified Trainer profile, you say that you use Live Racks to improve the efficiency of your work. Can you tell us how you use the Instrument Rack and Audio Effect Rack?

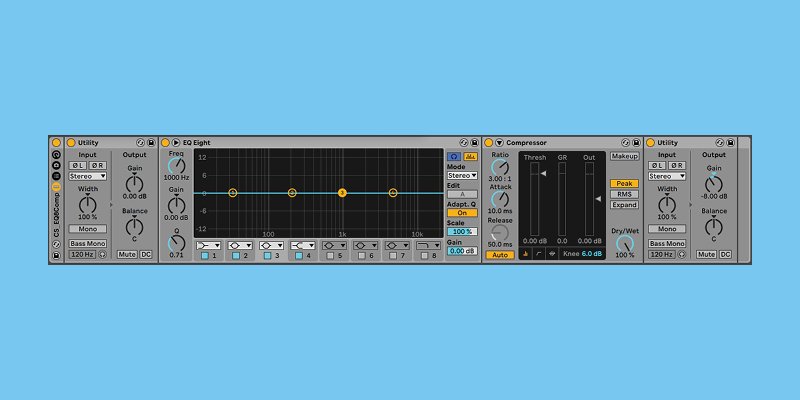

When I create a new MIDI track in Live, I have the Audio Effect Rack with Utility, EQ Eight, Compressor, and a second Utility all automatically set up in a chain to start with. I use the first Utility to adjust the input gain. After that, I mix and play with the sound using EQ Eight and Compressor, and the last Utility is used to set the balance and left/right imaging. If necessary, I’ll add some reverb or delay devices to the chain. I also have a few self-made presets for Pedal, Amp, and Cabinet that I often use. In the Racks I’ve made available for download, I have Pedal_Amp_Cab_Heavy, Pedal_Amp_Cab_Rock, and Pedal_Amp_Cab set up. With this kind of guitar effect, the tone changes drastically when the volume is changed, so I saved my own preset with the gain set to get nice sounding distortion, and I start creating the sound based on that. This is how I created the demo song Pedal_Amp_Cab. Another thing I do is have my browser collection organized by type of instrument, so I can quickly find what I want.

The Device View when Okamoto creates a new MIDI track; a device chain of Utility, EQ Eight, Compressor, and another Utility are automatically loaded up

One of the Racks I’ve included in the download is called Bell Designer, which makes it easy to create the sparkling sounds that are often requested for games. In Live 11, the macros in the Rack have a randomize function, so I assigned parameters to the macros that would be interesting to randomize, such as the waveform position in Wavetable and some oscillator effects. When you press “Rand” on the macros, you can create more and more bell sounds. Game sound designers want a lot of bell sounds, but they don’t want to use the same sound every time. In the past, I had to manually change the macros, so I’m really happy with this new randomization feature. There is also a Rack called SynthBass Designer for synth basses and SEQ Designer for sequences. I’ve also prepared a demo song called DesignersRacks so you can try playing around with it by soloing each track and pressing Rand on the macros. It’s a conservative way to use the device, but it can help streamline the production of music for commercial use.

“Wow, I didn’t realize playing around with this parameter could create such a tasty sound.” It’s those kinds of discoveries that make a good day for me *laughs*

With a Rack like this, I can save a lot of time that would be spent on choosing the right tones. If you use the standard bell synths that come with Live or other VSTs, you’ll be doing the same thing and putting yourself in direct competition with other sound designers. But I think you can differentiate yourself by building your own original Rack. If you’re just looking for efficiency, you can just use the same project templates and presets each time, but you’d end up with the same sounds and instrumentation every time. So, for that reason, I don’t use project templates and presets and [instead] use customized Racks to streamline my work while still keeping a sense of originality.

I made the decision a while back that when I’m making music to never use a template for an entire project. This may sound a bit silly, but I don’t really like to write music; I think I just like playing with the equipment. I’ve been messing about with equipment all day every day, trying to figure out how to get paid for it, and that’s how I ended up in my current job *laughs*. Once you create a project template, you don’t give yourself many opportunities to play around with the equipment. So, for example, every time I use a drum sound source, I try to import waveforms that I’ve never used before, create them from scratch, and if I discover something new, I’m like, “oh, I didn’t know this function existed.” Or like, “wow, I didn’t realize playing around with this parameter could create such a tasty sound.” It’s those kinds of discoveries that make a good day for me *laughs*.

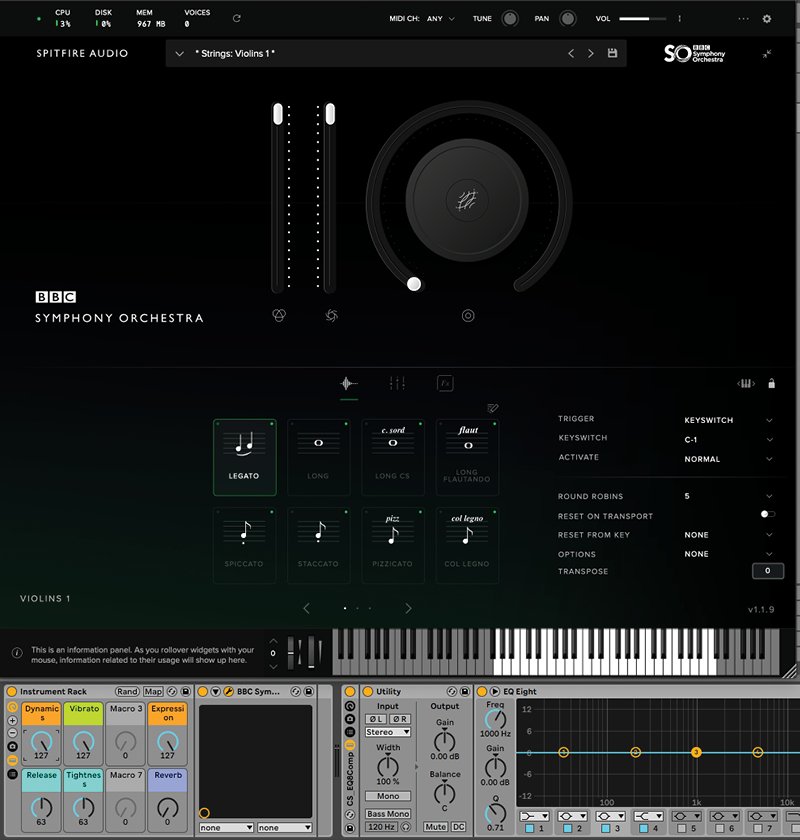

I also load orchestral instruments into my Racks, add some expressive parameters to the macros, and then assign them to the Push encoders so I can adjust them and get some real-time expression to the arrangement. The main orchestral instrument I use is Spitfire. During the summer and fall of 2019, I was working on music for three titles in parallel, and they were all orchestral. At that time, the textures of all the music became very similar, and I thought I’d get bored if I didn’t change something up a bit, so I worked with Spitfire for one title and a different orchestral plug-in for another. Each sound source or plug-in has a different feel and output, so the overall resulting sound changes as well.

By assigning expressive parameters for the orchestral instruments to the macros, you can quickly create the tone you want

The Criteria to Determine When a Track Is Finished

So, when you are playing around with parameters like that to create the sounds, how much time do you spend doing that before you feel like you’ve got it ready to go?

When it comes to the higher-register parts, I can get to a point when I’m happy with them pretty quickly, but for the kick and the bass, I’m constantly going back and forth on them up until the very last minute. Although I said I don’t use templates in my Live Sets, I do have templates in my head that I work from. I’m sure a proper composer would be angry to hear this, but I actually create the melody last, after I’ve finished the rhythm. I decide on the tempo, the rhythm, the chord progression, the bass, and then I start on the top parts. Of course, if it’s a piano solo piece, I don’t do it that way, but if it’s a track with a rhythm, I basically work in this order. This is the method of creating music that I have arrived at after a lot of trial and error. Normally, you should write the melody first, but I found that it wasn’t giving me the results I wanted, and I realized that it worked better for me to start with the rhythm.

When I’ve finished the beat, bass, and chords, I ask myself, “How much more do I need to do until this is finished?” in order to make a decision at that juncture. My main selling point as a writer is my interesting and elaborate chord progressions. I make music because I like the flow of harmony, and I’m quite particular about it, so my decision is based on whether I think it’s sounding interesting or not. For my final judgment of whether a track is complete or not, it is important for me to see if I’m still into it when I listen from a distance away from the speakers. I move back about two meters from my normal listening point, turn up the volume on the speakers, and then make a final judgment based on whether the track feels good or not. At that point, I’ll ask myself, “Could I improve on the current kick or bass?” I’m always really focused on the low end. I find this even for tracks without that much of a rhythmic element.

I get up early and start working on a track, and I will aim to have something ready by lunchtime for the intermediate decision about how to finish it. After lunch, I think about the main melody until about 1:30 p.m. If I can come up with a melody that fits the song, then 90% of the work is done. From there, it’s a matter of adding extra parts to fill out the sound so it’s rich and wide enough to meet the needs of the brief. At that point, you can quickly create dynamic layers of sound by duplicating the MIDI note phrase on a different track and using a different instrument, maybe arpeggiating it — just like the technique introduced by Ben Lukas Boysen in his One Thing video. I think the combination of this technique and the Racks I’ve provided works well together.

Have a Large Drawer of Ideas

After producing so many tracks, have you ever run out of ideas?

You know what, I haven’t! I think that studying up on stuff can prevent you from drying up. If you don’t consciously maintain the quality and quantity of your input, or learning, it will affect your output, and you’ll quickly run out of steam. So, if I hear a track I’m into on the streaming platforms, and I think, “oh wow, that’s cool,” I’ll want to play the track myself, try and copy the chords by ear, and pick up a new chord progression. I have a playlist called “Songs I Want to Make” on my streaming account *laughs*. The feel of the drums is another thing that interests me when I listen to a track. I’m always paying attention to things like interesting choices of beats at certain tempos, or where they’ve just got the snare dragging at a certain point. Besides that, I’m also interested to hear what kind of bass sounds tracks are using.

Music is very contextual, and when you hear new music, you’re like, “oh, this has evolved from trap,” or “this is what drum and bass sounds like now after dubstep.” Even though club music isn’t my main business, I sometimes make four-to-the-floor and drum ‘n’ bass stuff for work, and I don’t want to make something that makes people think, “this guy doesn’t understand the context of anything.” I have a lot of respect for originators. I try to listen to music as systematically as possible. That’s why I like the streaming platforms because they show that people who are listening to one track are also listening to this other track, so if you follow that or check out the artist’s social media channels, you can see what kind of artists they are connected with and where they sit contextually. This is also important information for me to “input” when I compose. It can be hard to find time to listen to other artists’ music on a day-to-day basis, but I do try to always listen to music when I’m driving.

Keep up with Takashi Okamoto on Twitter, Facebook, Soundcloud, and his website