SUGAI KEN: The Shibui of Field Recording and Electronics

In recent years, field recording has been slowly moving from the fringes to the mainstream. From its academic origins as a method of keeping a record or audio snapshot of a time and place for cultural-anthropological purposes, field recordings now often appear in popular contexts such as ASMR videos and background soundscapes for sleep or concentration. And as a compositional element in contemporary music the use of field recordings have become much more widespread as well. This likely has to do with the fact that it’s become easier and more affordable than ever to acquire a high-quality microphone or recorder and go out and capture environmental ambience. But how do different artists record sounds in the natural world while maintaining a sense of their own originality?

SUGAI KEN is an artist whose production style and musical roots come from a deep background in field recording. Since his first album 時子音 -ToKiShiNe-, released in 2010, Sugai has been expressing Japanese lyricism through environmental and electronic sounds. Having gained attention from prestigious labels outside of Japan, in 2016, he released 鯰上 - On The Quakefish on Melbourne-based label Lullabies For Insomniacs, and in 2017, UkabazUmorezU on New York label RVNG Intl., giving his music a worldwide audience. These key releases helped unravel his unique philosophy and methods.

In the last couple of years, he has released two studio albums. Tone River and Be Sure to Listen to This at Japanese Teatime both represent the artist’s current state of exploration into the fusion of specifically Japanese topography and traditional culture with electronic music.

Tone River, released on Netherlands-based record label Field Records, was commissioned by the Dutch Embassy in Tokyo. It was created in part to examine the relationship between Japan and the Netherlands involving water management. The album takes its name from the 322-kilometer river that stretches across the Kanto region, flowing into the Pacific Ocean from its source at Mount Ōminakami in Miniamiuonuma, Niigata Prefecture. The river was once known for its uncontrollable nature, but its present route was determined in the 19th century with the help of Dutch engineers.

In 2021, Sugai released Be Sure to Listen to This at Japanese Teatime, which features environmental sounds recorded in abandoned tea gardens. The album forms part of the “Tealightsound” music project of UJIKOEN Co. Ltd, a tea wholesaler that has been based in Kyoto for over 150 years.

These two albums formed the basis of our discussion with SUGAI KEN, and in this interview, the artist explains how he uses the sounds he collects from field recordings in his work. We also ask him about his thoughts on aspects of Japanese culture that are significant to his music-making. SUGAI KEN also generously produced a special set of field recordings to accompany this interview.

SUGAI KEN recording at a tea plantation

What equipment and plug-ins did you use in the production of your 2020 album Tone River? What sounds did you want to achieve with the set-up you had?

I used binaural microphones and hydrophones to record the environmental sounds. The binaural microphones helped create a sense of realism of being in the place that the sounds were recorded in. The hydrophones I used to record underwater, to convey that feeling of submersion to the listener. With the binaural microphone, I was able to record from a relatively wide range of angles. I didn’t use the microphone in any unusual way. I don’t really have a set process, it’s just a pretty standard way of recording, I think. Although, I do vary it a little. Sometimes I will stay with the microphone while recording, but there are other times that I will leave the microphone to record sounds and then come back later to stop the recording. There may not be much difference in the sound, but somehow I feel that I can capture the atmosphere in a more natural way by setting up the microphone and leaving it there on its own. For the most part, when people are doing field recordings, they will hide their presence as much as possible in the environment, keeping still and even holding their breath to not to make any sound, but when you think about it, that seems like a really unnatural way of doing things. On my track “Symphonic ‘Joya no Kane’”, I actually touched the microphone on purpose during the recording.

What kinds of environmental sounds make you feel you want to record them?

There are two things that come to mind. The first is a sound that is in line with the concept of the work. For example, for Tone River, the label asked for something literally related to a particular river, so I went and recorded that. The second is a sound that I am personally attracted to. In addition to sounds that convey a sense of daily life and regional characteristics, I also like to record sounds that emanate the uglier side of human desires, such as angry shouting, abusive language, and lies. I very often roll off the unnecessary lower frequencies of these sounds when working on the production and mixing. But it can be necessary for me to use dynamic EQ if it sounds unnatural when I cut out these frequencies in the same way.

The opening track “Headwaters of the Tone River”, contains exactly this kind of noisy voice recording. Can you talk us through this and how you achieved it?

I used a bitcrusher to process the voice. The headwaters of the Tone River are affected by environmental pollution, and I wanted to express this pollution with the rough and “noisy” sound that this effect creates. I’ve tried other effects, but I felt that bitcrusher, with the grittiness of the sound, can more truly express the foulness of the pollution. To give another example, on track 5 of Tone River, “Estuary of the Tone River”, the roaring sound around 2:13 was created by combining multiple frequency bands, which gives it this interesting vibration effect. I think I layered three or four different frequency bands on top of each other, and I was impressed with this peculiar groaning sound I got that sounded like wave interference phasing.

When doing the field recording for Tone River, how did you choose the sections you would use and which sections you wouldn’t?

As far as I remember, I recorded about 10 minutes at each location, and the total recording time was somewhere between 20 to 30 minutes. It was the first time for me to drive around 600 km in one day to record environmental sounds, and it was very physically demanding. The parts of the recording I used were parts where there were no sharp peaks in sound. If I had used the bits where the sound peaked suddenly, I would have had some difficulties keeping a certain amount of headroom. When I’m recording and using ambient sounds, I don’t want to use a compressor to squash the recording in an unnatural way, so I am very conscious about the headroom and increasing the volume of the recording in a more organic way.

What was your production process like when incorporating the field recordings into the music for this work?

For this album I treated the environmental sounds and the music separately. So, strictly speaking, I think I started writing the music before getting all the environmental sounds together. This is because I thought it would be better to separate the random, uncontrolled documentation of sounds and the more exact and intentional act of creating a piece of music – and then combine them together into one work. Actually, I started creating the music before the field recording, so I hadn’t visited the site, but I did some research about the history of flood control along the river, as well as other things to do with the river, and incorporated the images that came to my mind as I was doing this research into the composition.

The other notable equipment I used on Tone River, besides the microphones, was analog synthesizers because I wanted to create a feeling of warmth in the sound. But, I also used digital synthesizers to give the music some bright reverberation to the texture as well. When I was recording the synths, I used a transistor saturator to kind of blur the surface of the sound and some analog echo delay to give the stereo image a kind of soft shadow effect. I also used a vocoder to give the voice that electronic feel, and I ran the sounds through a reel-to-reel tape machine to add a kind of distinctive shimmer.

How did you approach how you structured the sounds and built up the acoustic space of Tone River?

I think that it’s more obvious in my recent work, but I try to be as faithful as possible to my own mental image of the landscape of how I want the acoustic space to be and where I want the sounds to sit within that. It may be an abstract expression, but when I capture a clear visual representation of this mental landscape, I try to find a way to express that “picture” in sound. For example, if there is a solid image on the left side of the “picture”, I put a solid sound panned to the left. If I see a soft image on the right side, I create softer sounds for the right channel – that kind of thing. Since there are infinite ways that each person will envision such a scene, I think there are no right or wrong ways to approach this.

If you compromise your approach or stray away from the “central pillar” of your artistic vision to chase easy success, then you won’t get good results in the long run. But as you continue making your art, you can start having an artistic ego and being more conscious of your public image. In that case, you paint the exterior of that pillar in the colors you want. Since 2010, I have been using a particular motif sound – a sound that many Japanese people have found nostalgic, as it resonates both linguistically and with a tradition of living in wooden houses. It’s a sound that apparently doesn’t seem to register in the same way in stone-house traditions like in the West. This motif is one example of the exterior painting of the central pillar that I mentioned; this motif is a “SUGAI KEN” melody that is part of the image of my artistry, a deliberate act of creating a feature that can make connections.

Recording underwater sounds near a grove of tea plants, being careful not to get bitten by leeches or horseflies

Moving on to Be Sure to Listen to This at Japanese Teatime that you released in 2021, what kind of sound and feeling were you aiming for with this work?

This release started with a request from UJIKOEN tea wholesaler in Kyoto. I think that track 5, “Cha to Kehai (Are you high purity?)” most closely resembles the image I had for this work. I felt that if I tried to make it sound like a “piece of music”, it would be too contrived and would not match the image I had. I felt that I would lose the purity of the sound, so as much as possible I tried to follow the picture I had in my mind when creating the sound.

Personally, I feel that the image of drinking tea as a “pure and innocent healing” experience as being somewhat shallow. I wanted to go one step further and express a kind of madness that floats in the air during the experience of drinking tea. Digressing a little bit from green tea, I read somewhere this shocking story about a samurai commander who was in a peculiar state of mind thinking that he didn’t know when he might be killed and had some exceptionally concentrated matcha tea and started tripping out before going back to the battlefield. I am personally drawn to this more extreme side of the healing process.

What are the challenges in reproducing natural sounds using electronic instruments such as on your album Goto No Yoniwa or the track “A Mysterious Voice Echoing in the Mountain Forest at Dawn, Reproduced with Electronic Sounds”? Can you give us some specifics about the production process?

I know it sounds like I’m stating the obvious here, but the sounds of nature are very organic. When they’ve been analyzed and there seems to be a pattern to them, in fact, there isn’t. The opposite is true too. This is why trying to replicate them is a very time-consuming process. You have to do the entire process manually, and you have to listen to the recording countless times in order to get it even remotely close to the analog waveform. When you are doing this, you can zoom in and see the waveform in detail by using a DAW. I also use impulse response (IR) data to measure the acoustics of the setting that I have recorded in to understand how the sound reverberated in even outdoor locations. By doing this, I can isolate the sounds like bird calls I recorded in order to recreate them electronically. I then apply the appropriate level of reverb to make them sound like they were produced naturally in the setting of the field recording, along with mixing in the parts of the field recording that contain just the noise floor. “A Mysterious Voice Echoing in the Mountain Forest at Dawn, Reproduced with Electronic Sounds” uses the actual local environmental noise floor. Only the bird and insect sounds are reproduced electronically.

SUGAI KEN's album Goto No Yoniwa reproduces the sound of insects using only electronics.

Where and how was the field recording done for the sound pack you kindly shared with us? What do you think are the highlights of the recording?

The recordings were made using binaural microphones and hydrophones at a stream near my house, at a cycle path rest area, a shopping mall, and a library. The highlight of the recording for me was when a male runner unexpectedly turned up at the cycle path rest stop and rinsed his mouth in a vulgar manner.

You make effective use of pauses and silences in your work. Can you talk us through what your intention is when you are using these pauses, and how you determine the timing of them?

Admittedly not everything, but I do feel that the source of trends in Japan still primarily comes from the West. I feel that the basic principles of the West are animalistic and based on the concept of rebellion and conquest. There is a lot of heavy pressure on people coming from the media, like the same way DAWs apply pressure to sound. Of course, I’m not saying I am against Western culture or badmouthing the West; it’s just an observation. In contrast, I feel that Asian cultures are much more vegetive, grounded in an underlying idea based on the principle of assimilation. However, I also think that the modern westernization of Japan has made us considerably more animalistic. And I have always felt that if we continue to follow western methodology, we will always be secondary. So, I’ve been working on my own trial-and-error approach to my work, and that’s where I am now. However, it’s still far from how I really want it. From a personal perspective, I am aiming to build a relationship where sound and silence complement each other, especially in my live performances. I think that the experience of reading the Fūshikaden* by Zeami Motokiyo also had a big influence on the basis of these ideas.

[*Fūshikaden, loosely translated as The Flowering Spirit, by Zeami Motokiyo, a sarugaku theater master active in the early Muromachi period (1336-1573), is the oldest book on theater theory in Japan, and has become the foundation not only of Noh theater but also of various other arts in Japan.]

Many descriptions of you as an artist emphasize that you are very “Japanese”. What do you think about this image people have of you and the overall concept of Japanism? What are the ways to express this Japanese sentiment without using symbolic sounds, such as Japanese instruments?

I leave it to the listener to decide whether my work is Japanese or not. I always struggle with how I can express the concept that my work is Japanese music. I try to be clear about my rationale, but I do also enjoy a certain degree of “frivolous” creativity. This may be moving away from the subject of Japanism, but I would like to make two points about Japanese culture.

The first point is that the common understanding of the Japanese word “shibui” [an aesthetic of simple, subtle beauty] is a really important notion at the heart of Japanese culture. The word “wabi-sabi” has now become more of an exported concept but that’s not what we see in everyday life in Japan. However, the word “shibui” is something that still appears in daily conversations. I think that Japanese people should take a fresh look at the value of this precious common thread. The word “wabi-sabi,” particularly if written in the Western alphabet as an exported concept, may have become somewhat of a useful parody, but the traditional concept of “wabi-sabi” is still important. The “wabi” is close to the word “seihin”, meaning honorable poverty, but my own interpretation of it is that it is a state of revelation where you get bored of established aesthetics or trends and form a desire for another value in simpler or more tattered things. I think it also encompasses a toughness to enjoy the reality of things when they don’t go the way you wanted them to. I interpret “sabi” as a sense of compassion for impermanence and the inevitability that all things eventually grow old.

I feel that the emphasis on youth culture is still too high in contemporary Japan, even though the time in our life when we can describe ourselves as “young” is relatively short. I have witnessed many people “graduating” from the world of cultural creation around the age of 30. This is probably partly related to the long working hours in Japan, a well-known bad practice. On the other hand, the aspect of Japanese culture that Japan is most proud of exporting to the world is what we would describe as “shibui”, right? And a lot of that culture was created by our ancestors who blossomed as they aged, with their art becoming deeper as they grew older. My hope is that we will see a wave of mature and highly concentrated personal expression in the mainstream. This distilled joy of art and aged eccentricity is what I’m waiting for.

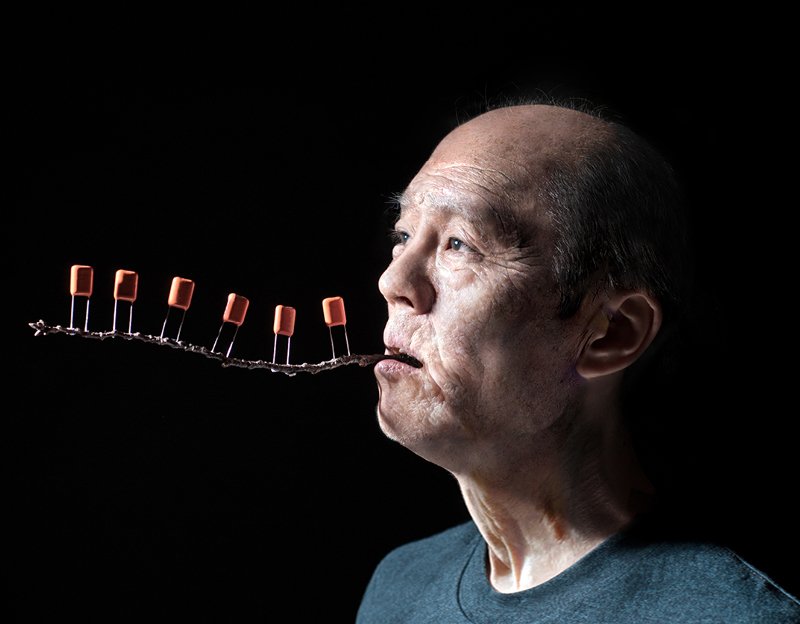

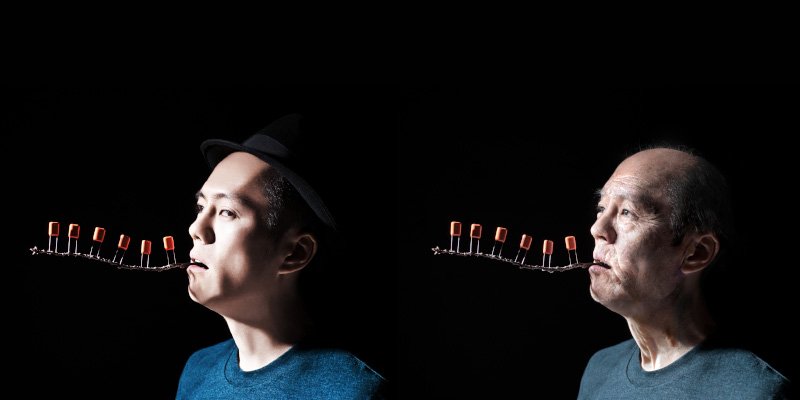

Left (2012), SUGAI KEN parodies a famous statue of a 10th-century Japanese Buddhist monk Kūya. Right (2020), the artist digitally aged himself. The artist’s photo references the early-modern Japanese art of yatsushi, the process of representing a classical episode in modern dress

The second point is that many Japanese people are still unaware of unusual elements of their culture. Here are some videos that illustrate that point a little.

Hosting meals for invisible god of the paddy field

Although it’s not mentioned in this video, I heard that as a form of hospitality to the unseen gods of the rice paddies, the master also takes an air bath with them in the nude.

This is nothing but brilliant, including the blank expressions of the children watching.

The surrealism of it all.

I would like the readers of this piece to immerse themselves in extreme Japanese folk culture and ancient Japanese history and sublimate it all into their own creations. From Icchu, the legendary 14th century master of dengaku [a kind of ritual music and dance for shrines and temples, often associated with rice festivals] to 11th-century genius gardener Enen, to Ryo Okawa, who preceded Muneyoshi Yanagi [the founder of the Japanese folk craft mingei movement, which promoted the art of everyday objects created by anonymous or ordinary craftspeople]. And from [the late 19th-century, early 20th-century Koto music composer, and a pioneer of Kyougoku style] Koson Suzuki, who was already capturing sound into colors back in the Taisho Period [1912-1926], to Kazuo Iinuma, who saw rhythm as a cycle, akin to Murray Schafer, and who stated, “The life and movement of people fall in a fixed rhythm”. There are endless greats waiting for you if you dig deeper.

Download SUGAI KEN’s free field recordings

Text and interview: Keita Takahashi

Translator: Matt Lyne

Photos courtesy of SUGAI KEN

Follow SUGAI KEN via the links here: Linktree