Sounds from the Polish Radio Experimental Studio

At the end of World War II, the formerly independent country of Poland found itself firmly within the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence. Despite brief periods of liberalisation, the next 40 years under communism were an era of political and economic repression that only came to an end in 1989 with the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc of allied socialist states. For many Polish artists and musicians of the period, censorship was a constant concern and repercussions could be harsh for creating work that was deemed to be decadent, anti-Soviet, bourgeois or simply not compatible with the state-sanctioned aesthetic of ‘socialist realism’.

It is therefore surprising to learn that despite the circumstances, one of the first institutions in Europe dedicated to experimental and electronic music was actually founded in Poland. Set up in 1957 to create musical 'illustrations' for movies, radio and television, Polish Radio Experimental Studio (PRES) was an island of artistic freedom throughout the 1960s, 70s and 80s. As one of the few studios in Eastern Europe with electronic music equipment, and crucially, engineers who could service it, the PRES was a center of research into the possibilities of tape music and saw the creation of many astonishing original electro-acoustic works.

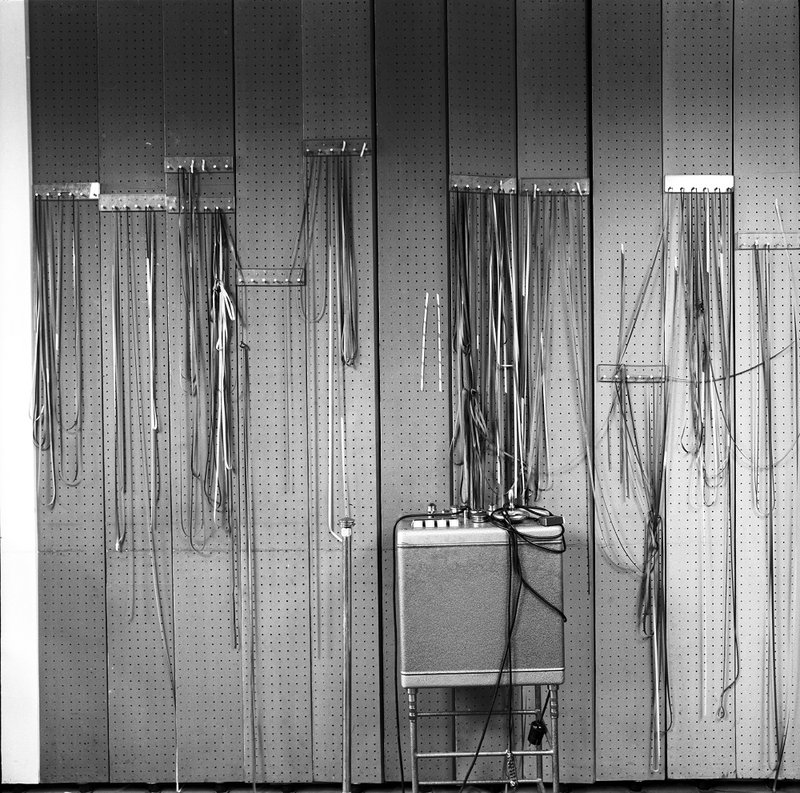

Polish Radio Experimental Studio – equipped for tape music experimentation

While some of the studio’s Western counterparts (the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, the San Francisco Tape Music Center, GRM in Paris, the WDR Studio for Electronic Music in Cologne) were respected cultural institutions in their day (and have since taken on near-mythic status), the output of PRES remains underrepresented in the history of 20th century music. Now, in an effort to make the story of the Polish Radio Experimental Studio more widely known, the country’s cultural institute, Instytut Adama Mickiewicza (IAM), has commissioned a sample library to be produced from some of the works made at the studio by composers Krzysztof Knittel, Elżbieta Sikora and Ryszard Szeremeta in the 1970s and 80s.

We’re thrilled to share this special free collection of sounds and devices with you. This includes nearly 300 sounds, loops and effects organized into Drum Racks, with custom designed Effect Racks and carefully chosen Macro Controls. Download the Pack below and read our interviews with project coordinator Michal Mendyk and Ableton Certified Trainer Marcin Staniszewski, who assembled the Pack.

Download free Sounds from the Polish Radio Experimental Studio

Please note: Live 10 Suite or above is required to make full use of the devices included in this download

Adam Mickiewicz Institute gives general authorization to anyone who would like to use the samples in any manner, including their unlimited processing or adaptation

Interview with project coordinator Michal Mendyk

Can you briefly sketch the origins of the Polish Radio Experimental Studio?

Polish Radio Experimental Studio was one of the first electronic music centre in Europe, founded in 1957 in Warsaw as a department of state Polish Radio. The founder of the Studio was Józef Patkowski, a musicologist and expert in early electronic music. What’s interesting is that Patkowski was strongly supported by Włodzimierz Sokorski, a radical Marxist, chief of Polish Radio and former minister of culture of People’s Republic of Poland. Paradoxically, a couple of years earlier, it was Sokorski who introduced social realism and radical political and aesthetical censorship in Polish art and culture. He was famous for having said about Witold Lutosławski, one of the leaders of Polish music vanguard that “he should be thrown under a tram”. So, in 1957 the same guy was responsible for creating the most experimental music centre in the whole Eastern Europe! He later said that Polish Radio Experimental Studio was his way to redeem his previous sins. This is one of many example of how paradoxical cultural and intellectual life in an authoritarian system can be.

Along with the Experimental Studio of Slovak Radio in Bratislava, the PRES was one of the only official institutions where electronic music was produced in Soviet-dominated Eastern Europe. Were the activities of the PRES ever overtly politicized, either positively as evidence of the “progressive” nature of socialism, or negatively as an example of “bourgeois” cultural activities that should be suppressed?

The situation of Polish culture was very special in the Eastern Bloc. After the death of Stalin in 1953 and the change of government in Poland in 1956, there was a strong tendency towards liberalisation in social life – what was known then as “The Thaw”. Although in many disciplines this tendency was later reversed, it did not change in art and culture. Of course there was a strictly political censorship, but almost no aesthetical one. Actually progressive, even avant-garde artists were strongly supported by the government as a part of official propaganda that was trying to say “We are socialist and at the same time we are progressive and liberal”.

Thanks to this paradox, the international careers of such figures as film director Andrzej Wajda, composer Krzysztof Penderecki or theatre director Jerzy Grotowski became possible. This was not the case in any other Eastern Bloc country where artistic experiments were restricted, if not strictly prohibited. For example, the Experimental Studio of Slovak Radio, created in 1965, regularly faced problems from the side and produced only a couple of dozen works.

At the same time, Polish Radio Experimental Studio produced over 300 hundred autonomous works and even more soundtracks for radio, film and TV. It also regularly hosted both young and renowned composers from the West, including Arne Nordheim from Norway, Lejaren Hiller from USA, François-Bernard Mâche from France or Franco Evangelisti from Italy. On the other hand the Studio was a part of socialist system. Therefore, although in practice it concentrated on autonomous experimental works, officially it’s main task was to create incidental music for radio, TV and film. So again, there emerged interesting paradoxes. For example the same composer could create experimental work with hidden anti-government message one day and on the next he was hired to produce the soundtrack for a pure propaganda film.

Eugeniusz Rudnik, a pioneer of electronic music in Poland, working at PRES

Unlike figures such as Iannis Xenakis, Pierre Henry or Luc Ferrari at GRM in Paris or Karlheinz Stockhausen at Studio für Elektronische Musik in Cologne, the composers working in the field of electro-acoustic music at PRES remain fairly unknown. What do you think explains this? Was it just a matter of Poland being outside of the European/American record industry? Or was the music or the composers’ activities somehow suppressed?

One important reason is of course that Polish Radio Experimental Studio was neither as advanced nor as productive as GRM in Paris or WDR studio in Cologne. This is a fact. On the other hand, in so called contemporary “serious” music there are still very strong “national centers” in Germany, France and America that largely focussed on what happens in their own milieu, without deeper interest in the peripheries.

Secondly, PRES did not have important achievements in the digital domain, in a way it has remained a purely analogue phenomenon. Its “golden era” was in the 1970s, more than 40 years ago. Many of the best works have been forgotten, especially because in the last quarter of the 20th century in Polish and Eastern European “serious” music has been dominated by conservative, neoclassical and neo-romantic tendencies. From this point of view experimental works were considered nonsense.

Also, after the fall of the iron curtain, artistic circles in many Eastern European countries became extremely interested in exchange with Western cultural circles, and very often undervalued their own tradition. It's only now, after almost 30 years, that this tendency has changed. Experimental music is a special case, I believe – in the post-techno era, there seems to be a global tendency of searching for the analogue roots of our contemporary digital sound.

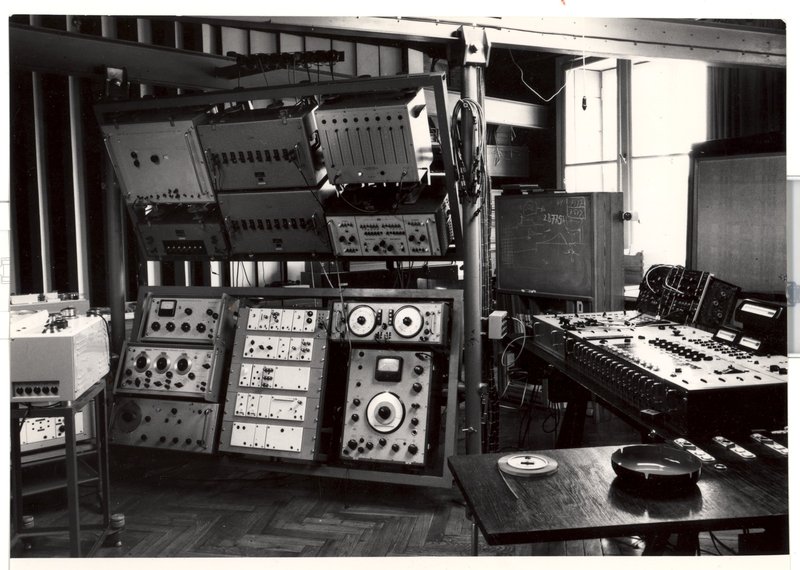

Tape machine, mixer, filter banks, oscillators, chalkboard, giant ashtray – the classic 70s electronic music studio set-up at PRES.

And how did you come to the idea to use the recordings from the PRES archive to make a shareable sample library?

I could just say that creating samples is nowadays the simplest way to give archival recordings a second life. But I also strongly believe that Polish Radio Experimental Studio archives really fit contemporary music production practises. Actually, many PRES composers worked in a way that is more similar to contemporary music producers than to “serious” experimental music music composers from Germany of France. The latter were deeply involved in sophisticated artistic theories or advanced technological experiments. Most of PRES composers on the other hand, were as involved in experimental music as in incidental music and these two fields often mixed in very interesting way, making their film music more “experimental” and their experimental music – more emotional, sensual and accessible. On a technical level this means: the practise of sampling their own or other composers’ works, as well as popular songs; reusing the same material in different compositions in a “remix-like” manner, adding regular rhythmic pulses to experimental sounds and textures, etc.

Interview with sound designer Marcin Staniszewski

You are an Ableton Certified Trainer, a musician, a producer and you work as a sound designer for apps, film and television. How did you find the experience of digging through the archives of your own country’s experimental music?

It was an ear opening experience. I was aware of Polish Radio Experimental Studio and most of the notable composers that were active during its existence but I was astonished by the quality of sounds, and the unique timbres and textures they achieved with such limited tools compared to current technology. It's just mind boggling. The coolest thing for me was that most of that music is not super tight in terms of certain BPM or grid. It’s usually improvised and very alive, evolving all the time.

Digitized stereo tape mixdowns served as source material for the free Pack

What was the state of the materials you were given access to and how did you go about organising it?

I received digitized source material. Most of the material was recorded to tape, by professional engineers, and you can definitely hear that. I was given access to stereo mixes, so I had to be creative because it was often a challenge to find the right moments to cut the samples. As I was digging thru the material, the majority of the samples fell naturally into one of three categories - it was either some percussive sounds, sound effects or rhythmical loops, so I did not have to think too much about it.

How / why did you decide to put the material into Racks and Audio Loops?

I decided to use Drum Racks as to me they are the essence of Live – the most creative and, at the same time, simplest tool. There are just endless possibilities with all the chains, grouping and macros. It’s also a very clear structure, so it was also very natural for me to put the samples in Drum Racks. As for loops, I didn’t really care if they are looping in a conventional regular manner. I was only looking for a grooves, and the weirder, the better. I mean I had access to some eccentric, crazy stuff, so I had to explore that side of it. I just wanted to be sure that it loops seamlessly. Don't ask me about the tempo or time signatures though!

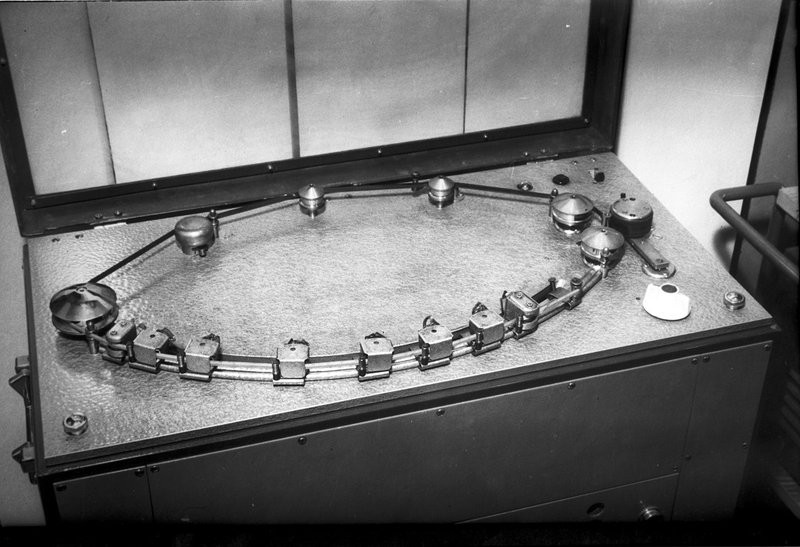

One of PRES’s tape loop machines

What surprised you most during your work?

I discovered that compressors are one of the most overrated tools nowadays. All these compositions are very dynamic, to such an extent, that even a simple white noise burst was giving me goosebumps. There are some soft passages followed by noise explosions and such things create another level of tension. This dynamic dimension is lost nowadays and it’s a shame because it can be so powerful. No wonder why some old school engineers use compression so lightly.

Also, as I was working on the tune showcasing this library (I liked the idea so much that I started a new solo project called SICHER and you can expect at least an EP very soon), I was amazed by how much one can squeeze out of one loop or one sample. It’s so much fun and so much more coherent when you use just three or four samples and then mangle them to death instead of using 100 different samples from all over the place. You can be sure that they share a common "timbre signature" and its not limiting at all. I found that I can make a whole drum kit out of one simple sound! It's just the matter of super simple operations like adjusting the start/end point of sample, or pitching it up and down. You want a clicky kick drum? Just move the damn start point so it does not fire off at the zero crossing and you got a nice click that will cut through the mix.

The composers

Krzysztof Knittel is a sound engineer, composer, performer, music journalist, social activist associated with the independent culture community during the martial law years, academic organizer and lecturer. Knittel has worked with a variety of styles, genres and techniques but one constant among all them has been his interest in electronics, which brought him to the Polish Radio Experimental Studio in 1973.

Elżbieta Sikora began her career studying under Pierre Schaeffer and François Bayle, two key members of Groupe de Recherches Musicales. She has been associated with the Polish Radio Experimental Studio since the 1970s. After relocating to Paris in 1981, she has worked at a number of renowned electronic music studios and composed orchestral works and operas, many of which show strong traces of electronic narrative.

Ryszard Szeremeta is a composer, conductor, and long-time head of the Polish Radio Experimental Studio. He also produces records, concerts, and electro-acoustic music performances, and was a member of the semi legendary Polish jazz quartet Novi Singers.

Download free Sounds from the Polish Radio Experimental Studio

Please note: Live 10 Suite or above is required to make full use the devices included in this download

Adam Mickiewicz Institute gives general authorization to anyone who would like to use the samples in any manner, including their unlimited processing or adaptation.

Learn more about Polish Radio Experimental Studio.

Follow Marcin Staniszewski on his website and download the full Live Set of his track “This Is P R E S”, which uses mostly sounds from the P R E S Pack.

Photos by Andrzej Zborski, 1962–1972, Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw.

The project is co-organised by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute as part of POLSKA 100, the international cultural programme accompanying the centenary of Poland regaining independence.

Financed by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage of the Republic of Poland as part of the multi-annual programme NIEPODLEGŁA 2017–2021.