Sounding the Collection: Samples from the Powerhouse Museum

Sampling has been a key process for a great many music makers for decades now, an undeniable staple of modern production. But with the ubiquity of sampling comes what feels like a sheer avalanche of samples. An overwhelming volume of sample packs are available online today, ranging from common to exotic, from free to eye-wateringly expensive, all vying for attention in a super-saturated market.

This kind of accessibility might sound like a dream come true to those who remember genesis of the art form – those first waveform explorers on devices like the Fairlight CMI or early Akai and MPC grooveboxes. But too much of a good thing can have a counter-effect; the paradox of choice paralysis, a psychological state in which an individual is unable to act for fear of making the wrong choice among too many options. Additionally, some collections of samples have become so popular they’ve become clichés, where some sounds have been sampled and re-processed so many times they lose whatever it was that made them special in the first place.

At a time where creating a truly unique group of samples seems an impossible task, Sounding the Collection has done the impossible.

Standing The Test of Time

Situated across four sites on Gadigal and Dharug land in Sydney, Australia, the Powerhouse is a museum group that has been active in one form or another since 1879. A popular fixture for school field trips, educational workshops and cultural programming alike, its chief purpose is the cultivation and celebration of significant items related to machinery, design, technology, fashion, space exploration and industry in general. Under the banner Sounding the Collection, the Powerhouse recently began chipping away at a gargantuan task: sampling some of their 500,000-strong collection of historical industrial objects.

“Sounding the Collection was a response to the Powerhouse's extensive digitisation project that began in 2019,” shares Mara Schwerdtfeger, audio producer at the Powerhouse, “setting out to digitally capture around 338,000 items from its expansive collection to allow for new levels of access to the collection. To add further information to this visual documentation, our project’s focus was to capture and digitize the sonic possibilities of some of the museum’s collection objects.

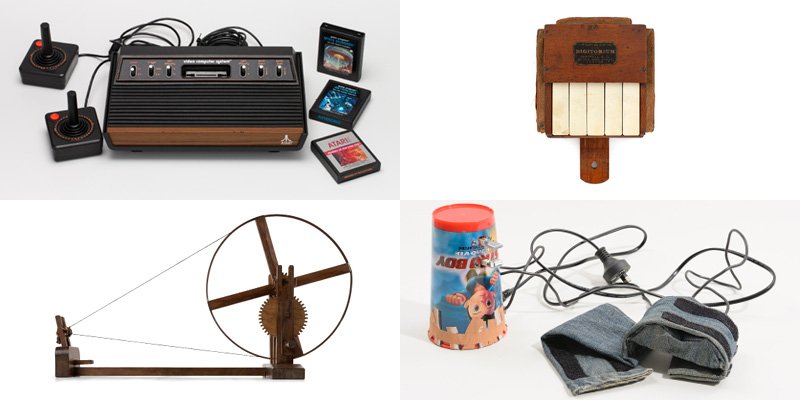

What we found was that each object and their sound had now become ubiquitous with a certain era or culture, offering a glimpse of nostalgia through the click of the Atari console (Object No. 2003/119/1) or geographic familiarity with the press of the pedestrian button (Object No. 87/234).

Atari video game console and cartridges

The project started in 2022. Every fortnight Cara Stewart, Sam Vine, and I would head out to the collection stores where we would work with a conservator to record a selection of objects in a small sound booth. We’ve now recorded over 100 objects from the collection.”

There are many factors at work here that can multiply an object's uniqueness; age, discontinuation, initial or eventual rarity, and context. Beyond these, there are sonic imperfections which have been introduced to the objects due to degradation.

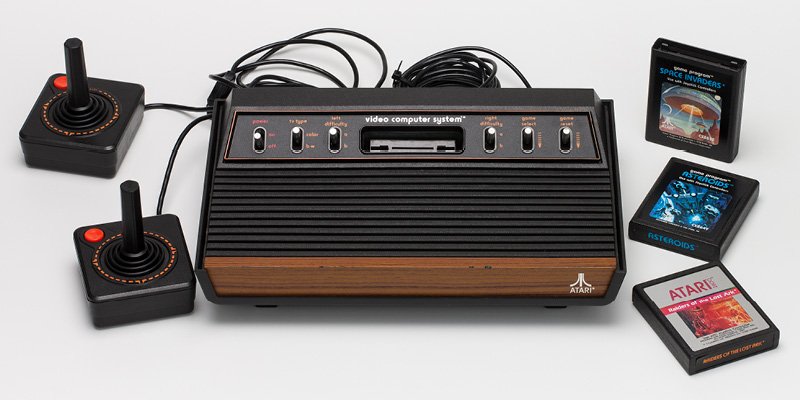

Picture book with built-in sound effects

“There are some objects that have deteriorated over time and the sound we were capturing has become unique to that specific object in our collection. The Speaking Picture Book (Object No. H7407) is one of these objects; a picture book with built in sound effects that are triggered by strings being tugged. The sounds play inconsistently with each turn, often sounding deflated. If we were to record some of these objects again in 50 years their sound could have changed or maybe even disappeared.

Irish harp

It was a similar situation with the Irish Harp (Object No. H9364). We played it as it was, straight out of the storeroom. We didn’t tune the strings in case any of them snapped. Additionally, no one present was a harp player and that knowledge can immensely change the sound of a musical instrument.

So, there is a lot to consider when creating a sonic archive – do you want to capture it as an object in a museum or as an object in the world? The hope is that by providing this sonic dimension of the objects their context and function can be understood further.”

Digitorium

A story behind every object

So far, Sounding the Collection has been focussed on recording objects that aren’t instruments – though many strange, rare and wonderful instruments remain in the Powerhouse’s vast stores. “I think there is an interesting twist to some of the objects we’ve recorded in that they belong to a music context but don’t actually make a musical sound,” Mara continues. For example, the Digitorium (Object No. 2001/12/1) was used to strengthen the fingers of keyboard players. The object consists of a group of piano keys that aren’t attached to any hammers or strings so the sound it produces is a gentle tapping.

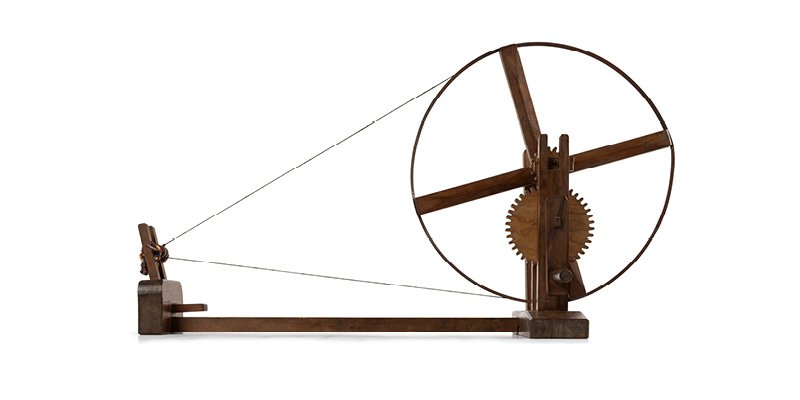

Handmade massage machine

Another interesting object is the Handmade Massage Machine (Object No. 2016/48/1), made with discarded materials by [engineer, artist, and inventor] Majid Rabet while incarcerated at Villawood Detention Centre in Sydney. The assemblage of this unique object made it completely mysterious as to how it would sound. It has a steady pulsing buzz and a gentle glissando when powering off. During this recording session we also had research fellows Sonia Leber and David Chesworth with us. They brought along an electromagnetic recorder which gave a whole new voice to this object.”

There are many reasons a museum may choose to catalog an object, be it for artistic merit, technical ingenuity or something more mundane. Historical significance is often realized in retrospect; such was true of discontinued instruments like Roland’s TB-303 or TR-909, which earned their fame long after their product life cycle.

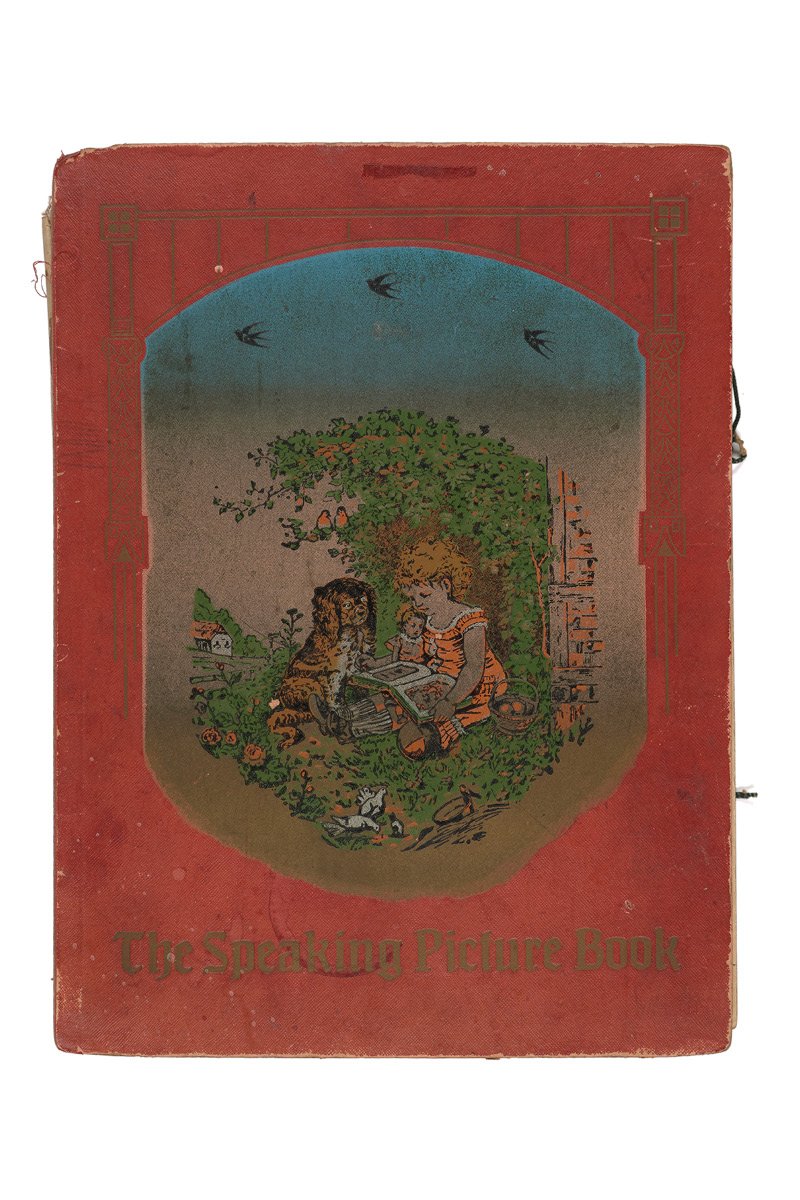

Spinning wheel from Japan

But even mundanity itself can be noteworthy, under the right lens. A machine destined to break down grain presumably wasn’t designed with the slightest consideration to the sound it may make, but here we are, recording such an object. Mara shares: “One of my favorite sounds we have recorded is the Spinning Wheel from Japan (Object No. 85/1433). It created a meditative sound comparable to wind blowing steadily through the tops of trees as the fabric belt moved around the two wheels. I love that one object can represent a landscape and trick the senses.

Mechanical grain mill

Another favorite is the Mechanical Grain Mill (Object No. K599). It has multiple layers of sound – a grumbling bass, an inconsistent clunking in the mids and a shimmering top frequency. These objects that have a circular shape and mechanical action create a constant drone of sound. The subtle rhythms you hear are artifacts of the object.”

Sampling as Conservation

The Powerhouse Museum and its personnel share the vision of conserving our human technological history and finding inventive new ways to share it with the public. Why else keep these objects, if not to learn from them and be inspired by what has come before?

In art, a sample can act as a gateway into a completely different time and context. The iconic string sample in Toxic by Britney Spears can lead a curious listener to Tere Mere Beech Mein from the 1981 Bollywood film Ek Duuje Ke Liye, for instance. Stock sounds in film such as the Wilhelm Scream have become referential icons of their own. The examples are as endless as they are intriguing.

So it is that publishing a sound, especially a royalty-free sound, invites the endless possibility of conservation and reuse through art. This too is a goal of Sounding the Collection, and to launch the project the Powerhouse Museum commissioned musical works by three artists; Salamanda from South Korea, Jonnine from Naarm/Melbourne and SOLLYY from Western Sydney, Darug Country. Each artist was asked to create a song from Sounding the Collection’s samples – three songs which have now been released.

“Beyond the digital archive, this project sets out to invite artistic interpretation and collaboration into the sonic archive,” Mara shares. “These recordings allow musicians, researchers, and sound designers globally to repurpose and interpret them — potentially finding their way into sonic identities, movie soundtracks, foley, pop songs, and sound installations.”

“The three commissions from Jonnine, Salamanda and SOLLYY show off how these foley effects can be integrated into music production. But their use can go much further too. For example, if people are sound designing a period film and need that specific James Oatley long case clock (Object No. H5639) we’ve now created that resource. Or maybe students are learning about the steam revolution and now they can understand the immense sonic energy behind those engines.

We’ve also been using them here at the museum to sound design podcasts (Culinary Archive, Oscillations), exhibitions (Future Fashion, Holidays), and films (Latitudes, The Lab).”

A Musical Touch

SOLLYY

SOLLYY is a producer, DJ and artist who stands as a key figure amongst the recent explosion of world-class hip hop that has rattled Western Sydney and beyond. His track, "STEAM ENGINE BLUES", revolves around more percussive Sounding the Collection samples such as the machinations of an intricate bird cage automaton (Object No. H5206) or the click of an Australian pedestrian crossing (Object No. 87/234-1), famously also sampled by Billie Eilish and brother Finneas in their hit "bad guy".

Australian pedestrian crossing button

“I was really drawn to the steam engine sample in the sense of using it as a metaphor for how I perceive myself continuously pursuing my career,” SOLLYY shared. “It inspired me to build the song around this motif of a steam engine constantly whirring and constantly going. It's a really driving sound. That's all I was thinking about when I was making that song – what really drives me to keep going in spite of all these obstacles and in spite of everything. The industrial revolution was because of the steam engine, and I feel like we're going through like a cultural revolution here in Sydney.”

Effortlessly flowing over this bedrock, SOLLYY references the familiar and contextual; Sydney nightlife, the scene around him and even Round the Twist, an iconic, nostalgia-fuel Australian television series.

“I use so many different sounds that have been sampled so many previous times in hip hop. Those sounds have such a lineage to them and using those sounds in my songs pays homage to the music that I listened to growing up and to the beautiful world of hip hop. So, it was really interesting coming into Sounding the Collection because it was the chance to do that but from a completely different historical context.”

Salamanda

“I thought it was a project that is similar to our slogan – every sound and noise can become music. So, while I usually choose samples for music production intuitively, this time I focused on listening to and selecting samples with small details.”

Salamanda are a Seoul-based electronic music duo, consisting of Uman Therma (Sala) and Yetsuby (Manda). As Manda shares above, they hold the firm belief that any sound can be musical, especially those we might initially consider simply noise – making them an ideal group to take on this project.

“I was particularly impressed with the photograph album with built-in music box sample,” continues Manda. “It had an antique and nostalgic texture, and the melody was memorable. My first thought was to preserve this melody line while working on the track. But in the end, I decided to chop this sample and put it into a sampler. Then we composed our own melody. When I listen to the sample as a whole it makes me take a trip to the past. But when I chopped it up and listen it feels mysterious, which led me to develop it into a folk-inspired melody and chord progression.”

Japanese drummer bear toy

Outside of melody, percussion was constructed from many sources, including the whirrs of a Japanese drummer bear toy from 1965 (Object No. 85/2575-29) and a winding Japanese lantern clock (Object No. A2976).

“We mostly put every sample into Sampler,” says Sala. “For this track I made a lot of percussion elements, so I put it in samplers and then added delays and reverb. The toy drummer bear sample I used sounded kind of like a glass sound, like a clinking sound. I really love turning samples into that kind of percussion sound.”

Jonnine

“I was on the hunt for sounds that had a keepsake narrative to them or that felt like they had a soul being passed on from generation to generation,” says Jonnine, one half of Naarm/Melbourne-based duo HTRK, who opted for an ominous atmosphere on her Sampling the Collection track "Shipwrecked".

“This is the first sample pack I've actually ever used to make my own music. I usually have a library of objects that I've recorded myself and they all hold some kind of memory or nostalgia for me. I record a lot of keepsakes like my grandfather's harmonica or my mother's pearl necklace. Vintage cups and teapots, buttons, shells, old keyrings.”

“Only recently I discovered that my great-grandparents and grand uncles were Eastenders from London who made clocks and watches. So I started there. I thought there was some metaphor there of the clock, not only keeping time but also keeping the memory of some of my distant relatives. They had to think about keeping time so much. It was their livelihood. All of this made me feel quite emotional and romantic and nostalgic for these objects. That was one of the reasons I was really excited for this project because I saw that [the Powerhouse] had all these eighteenth century or nineteenth century clocks and chimes.”

Photo album with built-in music box

First layering the sound of these ticking clocks (Objects No. 94/15/1 and H5639) with the looped hymn of a photo album’s built-in music box (Object No. H5397), the remaining space is filled out by Jonnine’s vocals, guitars and more samples from the collection.

“The song uses the theme of the Cerberus, which was a half-sunken ship near where I grew up and I wanted to write a whimsical pop song. The genre would be underwater pop.

Once I had my head in the theme of underwater, the typewriter in particular completely transformed into a little sand crab tapping on a rock. Suddenly everything stepped out of context and started to sound like a rusted old sunken ship. They completely lost all their value from where they're really from.

There's so much life in this sample pack and so much to explore that it could make you inspired to actually bring your own samples of life and your own field recordings into the mix and have it as a jumping off point for you to rediscover all the sounds in your everyday life again as if for the first time and out of context. The options are really endless to make these sounds completely your own.”

An Invitation to Create

To the Powerhouse Museum, these samples are a springboard. Sounding the Collection has just become a public archive and will continue to be used in projects internal or otherwise. As the collection grows, so too will the applications artists and other creatives find for it.

You’re also invited to become a part of the Sounding the Collection story. You can now download any of the samples straight from the Powerhouse Museum’s collection website, and below you can download both Ableton Live and Ableton Note sets featuring a curated selection of these sounds.

Download the free Sounding The Collection Live Project

Download the free Sounding The Collection Note Set

Keep an eye on the Powerhouse as the Sounding the Collection project continues to grow

Text by Tom Cameron

Artist Interviews by Mara Schwerdtfeger

Images courtesy of the Powerhouse