Having studied composition alongside Darius Milhaud and John Adams, computer music with John Chowning (the inventor of FM synthesis), and having worked as a researcher at IRCAM (birthplace of MaxMSP) in Paris alongside Pierre Boulez, Neil Rolnick is well-versed in the various currents of 20th century modernist music. Yet even after 30-plus years in academia, Rolnick’s views on composition and technology are anything but academic. Animated by the spirit of experimentation, his music is at times highly complex but never daunting and remains accessible, melodic and even, (dare we say it?) hummable.

One of the very earliest adopters (late 1970s) in the use of computers in musical performance, Rolnick has explored forms as diverse as digital sampling, interactive multimedia, vocal, chamber and orchestral pieces – consistently balancing his technologically sophisticated methods with a human element. His works often incorporate acoustic instruments, improvisation, steady rhythms, and real-time interaction between musician and machine.

In the midst of a flurry of activity, we caught up with Neil Rolnick to talk about his evolution as composer, teacher and technologist.

Music technology has undergone considerable change during your career. What would you say are the pros and cons of the move from hardware to software?

First issue: I think it's counter productive to theorize pros and cons of technological development. From a practical standpoint, things have changed, and I can either be part of the change or become obsolete.

That said, here's the balancing act as I see it. Software tools put a kind of musical power and flexibility at my control which I could never have imagined back when I was making 8 or 16 step sequences with Buchla or Moog analog synthesizers and composing with tape loops in the early 1970s. Or later that decade when I was working with non-real time computer synthesis at Stanford or IRCAM. Even when I wrote “A Robert Johnson Sampler” in the 1980s, I could only store samples of 5-15 seconds at a shot... so sampling and looping individual phrases was the best I could do. So the scale of what's possible now is great: your imagination has to go much further to push the boundaries of what the technology can do.

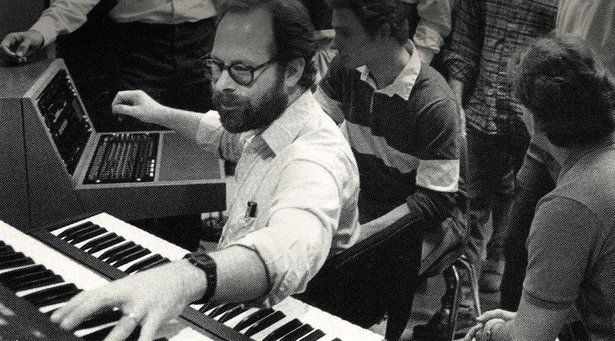

Above: Neil Rolnick's "A Robert Johnson Sampler", performed in 1988

On the other hand, as everything has moved to software, making music with electronics doesn't really require any physical interaction. It's easy to just hit the play button. But, at least for me, something is lost by not engaging our bodies in making music. So in all of my pieces, I try to design a kind of playing interaction for myself in which I really do have to focus and feel the music and make it happen. I'm preparing a new piece for piano and computer to be premiered in a couple of weeks, and I'm practicing my part hours each day, just as I would if I were playing an acoustic instrument. Back in the analog days, I had to do the same thing if I was going to perform live on a modular synth, with wires and knobs. Now, though, it's a choice I make.

How is it that your piece “A Robert Johnson Sampler” has stayed essentially the same even as you have ‘ported’ it from platform to platform?

The observation that “A Robert Johnson Sampler” is - musically - essentially the same as it was in 1987 is interesting. And it has to do with how I think about making music. Essentially, for me the sound and the idea of the piece comes first. Figuring out how to realize it electronically, or write it out for performers in the case of acoustic music, is a separate kind of activity. And while things I come across while realizing a piece may change some aspect of how I think about it ... the piece is still the piece. So, the fact that it doesn't change radically from one realization to the next just means that I'm able to master each evolution of the technology well enough to get it to do what I want. In terms of playing with the technology to exploit new possibilities, I tend to do that when I work on new pieces ... which I'm always doing.

So in porting “A Robert Johnson Sampler” from the original Mac Plus running OpCode's Sequencer, with hardware synths and sampler, to the current version in Live, was a matter of asking myself what was going to give me the sound I wanted, and what would allow me the kind of interaction I need in performance. Recently I've begun using the program Lemur on the iPad for controls. It allows me to still have an essential physicality in my performance, while also letting me re-imagine the ideal interface for each piece -- often letting me explore different sonic possibilities than I'd have available if I were limited to a pre-designed interface.

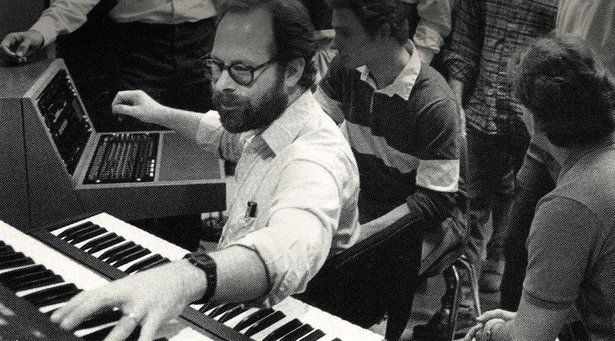

Above: Neil Rolnick's "A Robert Johnson Sampler", performed in 2013

You have recently retired from teaching full time. How does it feel to be able to compose full-time?

Yes, I recently retired after 32 years of being on the faculty at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. But I should also say that I've always been composing full time anyway … that's the only way I could have put out 17 CDs worth of my music during that time. And my attitude towards teaching is that the main thing I can teach is how to keep focused on making art and music despite the myriad layers of our lives, which usually include having to make a living, having families and relationships, and figuring out your place in the world. So if I'm not doing that myself, I really have nothing to teach. The musical and technological skills I taught were just a path to the bigger issue of being an artist and trying to understand what you have to say with your art or your music.

That being said, the escape from university bureaucracy after all this time has been incredibly invigorating. I'm still up at 6am to get started writing, and have a list of projects I'm committed to.

Among other things, I'm beginning to explore the possibilities of working with current technology performing mash-ups of music I love. Over the summer I wrote a mash-up of two Everly Brothers songs which were on one of the first LPs I owned when I was 10 or 11 years old. I've been playing it in concerts since August, and have been getting great responses from audiences. This is a form, or an approach to making music with computers which I engaged with intensively in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Coming back to it after nearly two decades is proving really interesting and exciting ... and I find that I perform on the computer much more securely and convincingly than I did 20 years ago. And my way of thinking about the music, about sampling and mashing it up, has certainly evolved.

What else are you working on currently?

I just released a new CD in October, Gardening At Gropius House with violinist Todd Reynolds, members of Alarm Will Sound conducted by Alan Pierson, and the New Music Ensemble of the San Francisco Conservatory conducted by Nicole Paiement. The next CD will be 3 pieces for solo virtuoso instrumentalists with interactive computer processing. The first is Dynamic RAM & Concert Grand which was commissioned by the Fromm Foundation for Bang On A Can All-Stars pianist Vicky Chow. It will be on a program with the two other large scale pieces I've done for piano and computer since 2005, each of which will be played by the person I wrote it for: Kathleen Supové will play Digits (2005), and Bob Gluck will play Faith (2009).

The next piece in my writing queue will be a piece for saxophone & computer, commissioned by the New York State Council on the Arts for Demetrius Spaneas. We're expecting to do a premiere tour of that piece in Europe and (maybe) Central Asia in 2014-15, as well as playing it in New York City. After that will be a piece for cello and computer.

At the same time I'm working on finding funding for a new piece for violin, cello, piano and computer for a festival in the spring of 2015. And I'm in the midst of a long term project called MONO, which focuses on the loss of senses. That is, sight, sound, smell, touch and taste. The project developed as my reaction to my own loss of hearing in my left ear in 2008; specifically, between 9:30 and 11am on March 30, 2008. It's not life threatening, and doesn't seriously disable me in my day-to-day life, but it had a big impact on me as a musician and composer. And as I spoke to people about the experience, I realized that many of us experience this kind of perceptual deficit or loss which we learn to live with. Eventually it will be a full evening staged event, but over the last few years I've written and performed about 2/3rds of the scenes individually, and have released two big segments on CD.

Find out more about Neil Rolnick’s many projects and download the Live Set of A Robert Johnson Sampler (requires Live 9 Standard or Suite) from Neil Rolnick’s website.