Jon Hassell: Possible Musics

“Like the video technique of ‘keying in’ where any background may be electronically inserted or deleted independently of foreground, the ability to bring the actual sound of musics of various epochs and geographical origins all together in the same compositional frame marks a unique point in history”, so wrote the New York trumpeter and composer Jon Hassell in the liner notes to his album Aka / Darbari / Java. The year is 1983 and the ‘unique point in history’ Hassell refers to is the advent of digital sampling, a technique which he’d made extensive use of on his then-new album. Remarkable for an artist working with a technology then still in its infancy, Hassell immediately recognized the potential of sampling as a new musical paradigm.

Or perhaps not all that remarkable. Having previously played and studied with Karlheinz Stockhausen, La Monte Young, Terry Riley and Pandit Pran Nath, Aka / Darbari / Java was already Jon Hassell’s fifth album and the finest distillation yet of an aesthetic he had been working in for several years; an approach to music making that, in conception and spirit, already anticipated the blurring of chronology and geography that sampling was just starting to make possible at the dawn of the 80s.

Hassell called the music he was inventing “Fourth World” and defined it as combining features of traditional musics from around the globe with advanced electronic techniques. In its highest form, the blend of influences would create the impression of a new, unified sound. Crucially, Hassell was careful to differentiate his projects from what he called “cosmetic” Fourth World – conventional musical statements with borrowed flavorings of exotic instruments, as well as from “covert” Fourth World – the structural framework of non-Western music borrowed and presented with Western orchestration.

Hassell’s earliest albums, made without the use of sampling technology – Vernal Equinox (1978), Fourth WorldVol.1 – Possible Musics (1980), and Dream Theory In Malaya (1981) – were decidedly not latter-day updates to the exotica canon, but nor were they jazz, ambient, minimalism, electronic music or ethnomusicological research. Instead, his was a much stranger brew that deployed all of the these elements to arrive at music that was “not entirely primitive, not entirely future but someplace impossible to locate either chronologically or geographically.”

Each album was an immersion in a richly detailed, mysterious and sensual world – and there was nothing like them at the time (nor is there now). One listener who picked up a copy of Vernal Equinox and was particularly impressed was ex-Roxy Music member and ambient innovator Brian Eno. After befriending Hassell, Eno went on to co-produce three of his albums and recycle some his ideas for My Life In The Bush of Ghosts – a collaboration between Eno and Talking Heads’ David Byrne. (Hassell was originally involved before he left the project due to artistic differences.)

Throughout the 80s, 90s and 2000s, Hassell continued to expand his sound into ever more lushly abstracted zones with the albums Power Spot, The Surgeon Of The Night Sky Restores Dead Things By The Power Of Sound, Maarifa Street and Last Night The Moon Came Dropping Its Clothes In The Street. The recently re–released City: Works Of Fiction from 1990 was a step into decidedly dancier territory and included a bona fide house track, “Voiceprint” – released at the time as a 12” with remixes by 808 State. Throughout this period, Hassell’s influence continued to spread, and he appeared on recordings by Peter Gabriel, David Sylvian, Kronos Quartet, Hector Zazou, David Toop, and Ry Cooder, among others.

More recently, Hassell’s name and the term “Fourth World” have been popping up with increasing frequency in some of the more forward-thinking quarters of electronic music. The Fourth World attribute has been attached to Don’t DJ, whose kaleidoscopic tracks blur the lines between synths, drum machines and gamelan orchestras. Montreal’s RAMZi has cited Hassell as an influence on her own music, which seems to similarly exist in a distinct space-time of its own. Adventurous DJs such as Glasgow’s Optimo crew and Salon des Amateurs resident Jan Schulte have put together compilations of Fourth World-inspired tracks from across four decades. And in the past few years labels including Music From Memory, Soave, Séance Center and RVNG Intl. sister outlet Freedom To Spend have reissued or compiled music by the likes of Michael Turtle, Roberto Musci, Michel Banabila, and Richard Horowitz, whose Hassell-inspired works of the 1980s and 90s now sound even more current than at the time of its original release.

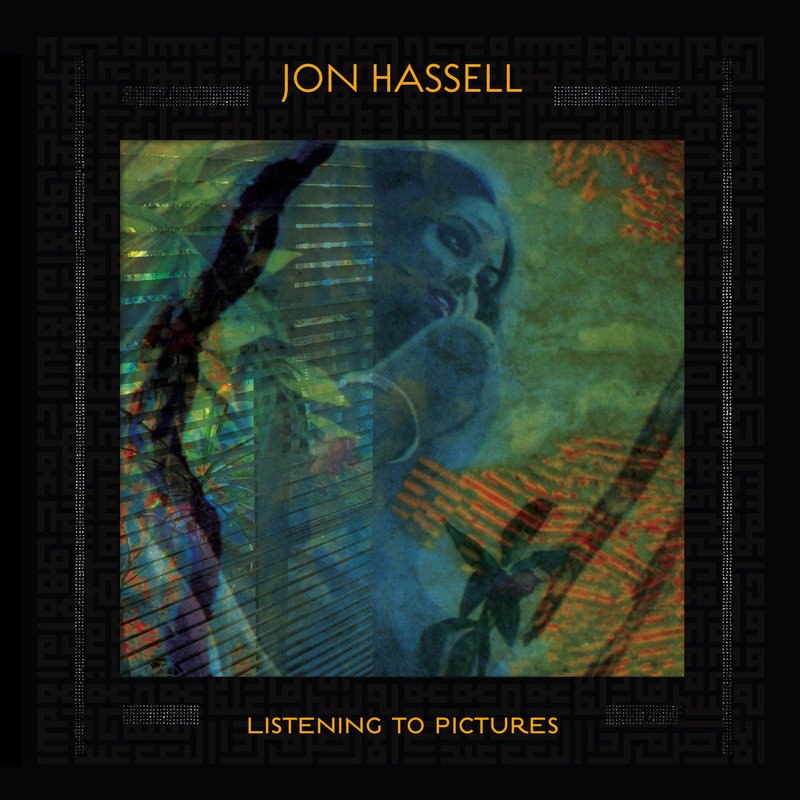

2018 then seems to be auspicious moment for Jon Hassell to release a new album. Listening To Pictures (Pentimento Volume One) is his first collection of new music for nine years and represents an updated reconfiguration of all the signature elements of Hassell’s magical realist soundworld: the lush chords and fine-grained textures, the oddly intricate rhythm structures that propel forward while revolving around their own axis, and of course, the treated trumpet lines, sounding somewhere between an intimate whisper and a chorus of conch shells.

We talked to Jon Hassell, now residing in Los Angeles, about musical roots, vertical listening, the rhythm of falling leaves and some of the other concepts that have informed his work over a lifetime of exploration and study with and among some of the most significant figures of 20th century music.

Have you been working on this new album continually since the release of the last one, or was there a break in between?

Actually it's like... imagine a slow motion movie of a plant growing. Little shards of this and little pieces of that go into concerts and then in the studio and gradually getting pulled together. It's a bit like the pentimento idea of layers showing through other layers. And each of those layers might be quite distant. Like if you think about Natalie Cole singing duets with her father [Nat King Cole], the time displacement is 20, 30, 40 years, so it's that kind of idea. I have such a collection of layers so just about anything I do is going to be a combination of older and newer. That's one of the ways in which that pentimento idea [pentimento: reappearance in a painting of earlier images, forms, or strokes that have been changed and painted over] applies to this record.

The cover of Jon Hassell’s new album layers several paintings by Mati Klarwein

It's also visually represented on the cover with the layers of Mati Klarwein's artwork. Along with Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock and many others, you’ve used a few of his paintings for your album covers. Was he a close friend of yours?

Yeah, he died a few years ago. We met in New York a long time ago and eventually we got closer. Later on I spent a lot of time in Deià, which is in Mallorca, where Mati lived and where the name of my label [Ndeya] comes from. I spent some of my best times there, in his place and this record is a tribute to Mati. And on the inner sleeves of the LP I did these visual pentimentos, which you could say is really a collage of things that were combined from my experience and from Mati himself painting something on canvas when I was there.

One thing I wanted to hear from you about is your history and evolution as a sampling artist. What were your first kind of encounters with using pre-existing sounds as part of your compositional process?

Let's see...

Did it have anything to do with Stockhausen by any chance?

Speaking generally, yes. I mean I spent two years in Cologne with Karlheinz Stockhausen. But sampling wasn’t in the "Wörterbuch" yet at that time. I think it's just more of a love and attraction to the idea of collage. But, it's not like the idea of collage means that what you arrive at is a collage. Just by searching for the thing that's appealing, the idea to have in mind is: What is it that I really like? I mean that's the question that I think every musician and artists and everybody actually, is asking themselves; what they really like. And that means the emphasis is on REALLY like, meaning how do you push aside what you've been told, what you've been taught, what your friends like, and how much you like something because your friends like it or because it's socially popular at the moment, or your girlfriend likes it or any of those ideas.

But back to sampling. Before I even went to Europe or anything like that I used to do a lot of tape splicing. There was this avant garde magazine called “Die Reihe” that was published by Stockhausen and Eimert and I remember reading about "Gesang der Jünglinge". Through that I was attracted to the idea of tape manipulation.

And of course the French were doing it with musique concrète, whereas Stockhausen was kind of more purist... electronic purity and all that, but that's actually where that whole sampling idea for me really got its roots. In that movement, in that particular time.

When I was in Cologne, or Köln – I'll use the umlaut – at the "Kölner Kurse für Neue Musik", the Can guys [bassist Holger Czukay and keyboard player Irmin Schmidt] were there at the same time. We hung out together and I think my first acid trip was with Irmin who had brought back some acid from Amsterdam. At his apartment I remember listening to... we were high, and I remember listening to Gagaku music – Japanese classic music, and like living inside of the rug on the floor. (laughs) I mean, it was a jungle.

But yeah, you're quite right to dig there because it was kind of the prototypical sampling wasn't it – chopping things up on tape. One thing I would do back then was chop up a vocal group called the Hi-Lo’s – a hip, modern vocal group with really interesting harmonies, really interesting changes and things. So I would chop up little pieces of that and I think those were the first things that I did that could be called a "collage".

Then, in the early 1980s, you began using one of the first sampling synthesizers, the Fairlight CMI, is that right?

Yeah, that was on one of my favorites: Aka / Darbari / Java. That was the first keyboard manipulation of sampled pitches. So I could play a Pygmy vocal sample, as parallel fifths or as another chord or something like that. That was 1983, and I think that was a super important moment in musical history, as far as I'm concerned.

Were you also using the Fairlight to make the rhythm patterns on that record?

No, those were all pretty much loops of Abdou M'Boup, the great Senegalese drummer, either slowed down or sped up and then layered. We'd make a loop around the studio, literally, with the tape going around mic stands. The tape would actually be coming through the [tape machine] head and going around the room because in those days you couldn't have a long digital loop like that.

Especially on Aka / Darbari / Java, on Dream Theory in Malaya and on Power Spot, the rhythms are often not obviously 4/4 but somehow have a very persuasive groove to them.

Yeah, that's the one thing I think has to be challenged – and this is not Ableton's fault or the fault of technology necessarily – but this idea that suddenly everything is 4 by 4 by 4, you know? I mean after all, if you're looking at other parts of the world and taking inspiration in that, then you certainly can't overlook the fact that certain feelings come from a way of imitating. I usually use the analogy of a falling leaf where it doesn't get divided up into 52 equal sections. I mean I suppose it could be recreated, but that kind of motion of falling down, catching a little breeze and then falling again, maybe being accelerated by something, that kind of movement is really beautiful. And that's why raga is so beautiful, because raga does that, also Persian music and African music too. Persian and Indian music more in the sense of melody but the rhythms of African music, or lots of it anyway, is that way too – it doesn't run by the metronome.

Right, so back to the timeline; I get the impression that your trajectory as an artist took quite an important turn around the time of your Cologne residency. I'm curious what you were doing even before then.

I mean going to the roots, I was born and grew up in Memphis. My father had a cornet lying around the house from a band that he had played in and so in grade school, when music was offered that was what I played. In high school I was really into Stan Kenton. I loved this big band atmosphere and the fact that he was so into the tropics, you know, and Cuba and all these exotic rhythms and things like that. Then I went to Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York which is a very conservative, academic place but with good teachers and that's where I got the university-type training.

I was studying composition and I was playing trumpet, I was in the orchestra but I settled in with the radicals there – with the four or five people who were aware of what was going on with Stockhausen and things like that. I got married after that, I had married a pianist, and we lived in Washington DC for three or four years. I taught theory for a year and then things were beginning to happen. There was this guy named Bob Moog who came around with his new idea of one Volt equals one octave, which became the Moog synthesizer. (We actually collaborated on a sound sculpture later; a tape loop within a box that had a double reflective mirror on the inside, and every time there was a "blip", a colored light went off. It was like this little fairyland of blips going by and each one had an output to six speakers around the room.)

Anyway, we moved to New York after that. And that's when the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst gave me a grant to come and study with Stockhausen and all the gang in Cologne. And that was amazing because I spent basically almost a whole year by myself there, and it was a real eye-opener for what living conditions were like. This was the mid 1960s and it was still cold water flats [apartments without central heating], schaschlik and bratwurst... no fusion cuisine yet. So it was harsh beginning there but it was a great boiling pot for all the "Die Reihe" gang.

Stockhausen has us doing these little exercises which had us trying to notate bursts of short wave radio. At the time, he was deep into doing this kind of graphical notation, gestural notation as opposed to using only standard notation of notes on a staff. I mean that was in there too, but it was a way of breaking up the texture, so that a brief passage of shortwave radio where one station is drifting into another station, when you notate it, out of that would come a melody...and that was a really interesting technique to think about. You could use it as sort of a graph but it also encouraged you to make pictures and to use them in the score.

So I spent three years there and I did a piece there called “Scan” that I guess would have been sort of a graduation piece, if you will. For that I had the technician at the studio at WDR make these little mixers that were just basically on/off switches, and I made these little keyboards of maybe five of these switches each. “Scan” used part of Schoenberg’s “Five Pieces for Orchestra” called "Sommermorgen an einem See” which is basically one chord which is morphing, going imperceptibly between a sustained flute to a viola to this or that.

I had the strings of the orchestras there play the excerpt from "Sommermorgen an einem See" and they played it all super pianissimo [pianissimo: very quiet] and they all had contact microphones on their instruments. And I'd made this graph score just by chance, you know, throwing dice and everything, and there was a score for the parts that were playing pianissimo to be brought forward and then muted at certain moments, which gave it this little structure. Unfortunately, I don't have a recording of that.

So what happened after Cologne?

So after that I came back to New York and started playing with La Monte Young and the Theater of Eternal Music doing these long Dream House things, the ones with the hashish milkshakes and the tuning up to 60 cycles. [Drone music pioneer La Monte Young tuned his instruments to the frequency of 60 Hz to ensure that the residual hum of electrical current - 60 cycles per second in the US - did not interfere with his music] When we did a show in Europe it would be 50 cycles so there would be no other stray frequencies in the atmosphere, so that was pretty amazing, that was where I kind of learned, or connected to the idea of vertical music. Which is just instead of listening to a line unfold in time, you’re presented with a timbre and you scan the timbre up and down vertically and listen to little areas.

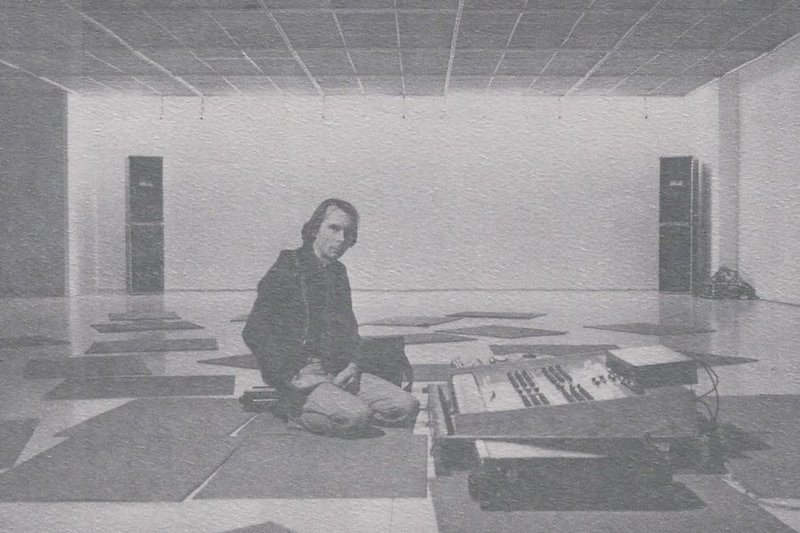

Jon Hassell in the middle of his Solid State installation

I did a piece called Solid State that was an outgrowth of that experience. Solid State was a stack of eight perfect (2:3) fifths creating a dense harmonic block which was time-sculpted with voltage-controlled filters. The concept was like beginning with a piece of paper that was all black with pencil lead and then making shapes on it by erasing. That was with using some early Moog equipment. The ploy at that time was that it was much easier to get a gig as an artist than as a musician, so I would present Solid State as a sound sculpture, which really it is, and so it would be done in museums with mats on the floor and that kind of thing. And that sort of came from La Monte Young too – that was the way a La Monte concert would be, people drifting in and out and all that kind of thing. Solid State was kind of a proto-electronica piece which, by the way, is going to be released on Warp.

And then came "Vernal Equinox" in 1978, the first record which actually incorporated a lot of the Fourth World ideas. That was the result of putting things together that were getting sifted down. I mean you're starting off and you still have other people in mind, you still have some La Monte in there, you still have Riley in you. Terry Riley was a big, big influence, absolutely – I actually played on the first recording of In C in 1968. I loved him and we had a kind of family thing going on too, with my wife and his wife and all that.

The distinction I made in the vertical / horizontal thing was 99.9 percent of the world listens in the horizontal way, which is: “Oh what's next, I like this, boom, oh no, what’s that, then comes this other event.” So, the vertical idea is going into a kind of eternal presence by learning how to kind of phase that out. And that’s La Monte's whole thing, although that's not confined to him at all, but it was of a piece with Terry Riley's aesthetic and is based upon these intricate, interlocking patterns, which then everybody picked up on, you know, Glass and Reich. But I feel lucky to have been connected with the progenitors rather than the people who were the spinoffs, let's say.

Another “vertical” aspect of your music seems to be in your trumpet playing – specifically, through the harmonizer and pitch shifter devices you’ve used throughout the years to make your trumpet sound like multiple instruments playing at the same time.

As far as harmonizers go, the very first one was Eventide, the Eventide H910 maybe? I forget the model number on it, they just gradually went up and eventually I had the biggest one, but it was so difficult to program. This new one, the H9 is the follow up which is all digital and just a little box with MIDI controls and that kind of thing. So I'm really excited by that, there is some of that on the record, and I'm really excited by the possibilities of that.

I've always been fascinated by parallels and by sequences, that kind of chordal movement in 5ths like you’ll find with Ravel and a lot of Brazilian music. There's some beautiful things by Ravel that I just adore. It's like, you start and you draw a curve on the wall with one pencil, then you take two pencils in your hand, and then you do the same thing holding two pencils or three. Then if things work out, years later, there's a technique for doing actual chord changes while you're doing that parallel thing. So yeah. I always loved the richness of the parallels.

Also, playing with [Indian classical singer] Pandit Pran Nath was fantastic, learning how to do the vocalisms, the curves and things like that. I always return to the analogy of the falling leaves, where you start and then you let it disappear and then you let it come back again.

Listen to Jon Hassell on Bandcamp and Spotify. Follow Jon Hassell on Twitter and Facebook.