James Krivchenia: Big Thief Drummer Samples YouTube for Blood Karaoke

James Krivchenia has certainly achieved a unique perspective across his career as a drummer, producer and engineer. He’s attained a rare fluidity whether acting as producer for experimental artists such as Mega Bog, crafting computer-based music on his own, sitting as a session musician for megastars like Taylor Swift or his main gig, playing in the visionary rock band Big Thief.

Anchored by the profound songwriting of Adrianne Lenker, Big Thief has naturally grown from intensely intimate folk music to a rare sound that feels unbounded by genre or time. Their one-of-a-kind music draws seemingly impossible comparisons, bringing to mind both The Band in their late ‘60s peak and Radiohead just before their own creative breakthrough at the turn of the millennium. After working as an engineer on the 2016 debut Masterpiece, Krivchenia joined Big Thief fully on their acclaimed 2017 follow-up Capacity and the dual 2019 breakthrough albums U.F.O.F. and Two Hands. Earlier this year he took over as producer for the band’s landmark fifth release, the sprawling double-album Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe In You, and now is ready to release arguably his strangest solo work — the fractured, sample-based Blood Karaoke. Taken together, they provide the perfect showcase of this artist’s ever-widening range.

Often built from highly processed samples, Krivchenia’s experimental, computer-based solo music is nearly unrecognizable from his work in Big Thief, yet it has evolved alongside the band from the start. The glitchy pointillistic rhythms of his 2018 album no comment utilized audio samples taken from body cameras in wars across the globe, while 2020’s A New Found Relexation used a palette of pleasure-inducing tones and soothing ASMR textures to create something subtly overwhelming. Rather than feeling beholden to the sample bases, Krivchenia uses those frameworks as a springboard into exploratory sound processing. The result is a series of albums that each convey some abstract, personal feeling even as they draw from the world around us.

Even compared to those previous albums, the framework of Blood Karaoke may seem impossible to pin down at first. The album opens with a blast of heavy metal guitar riffs that quickly melt into a bright EDM hook before further evaporating into brittle percussion that wouldn’t sound out of place on an Autechre track. A minute has not even passed and by the end of “Emissaries Of Creation” – one of the relatively simpler tracks on Blood Karaoke – it’s impossible to keep up with the number of sounds hitting you at once. What framework or limitations could possibly have resulted in an album that feels like having an entire music streaming service shot into your brain?

Every sound on Blood Karaoke was sourced through YouTube videos. Krivchenia has used YouTube as a source of samples on previous albums, but rather than searching for specific sounds, he immersed himself in the platform in a unique way. Using a program that pulls up random videos with less than 100 views, he surfed through clips like a modern public access TV station – finding corporate presentations, video game “Let’s Plays”, local news and phone videos with such low quality they were visually and sonically indecipherable. The result is an album that hits you like the blast from a firehose, but in the right light reveals an entire spectrum of beauty, terror, humor and vulnerability.

Sitting down over a video chat in the afternoon before a Big Thief show in New York, Krivchenia spoke with us about the weird world of Blood Karaoke, how his passion for computer music grew alongside his work as a drummer and how blending those approaches has helped him be a better engineer, producer and bandmate.

Sampling is such a foundational part of these solo albums you make. How did you first start to make music with a computer? Did your interest in sampling lead you to that or did it grow out of that?

I first got into computer music almost as a reaction to the burnout of drumming. I was in music school, so it's that weird formative time where you get caught up in stuff that you start to slowly realize is totally bullshit, like being "good" or something. I was playing a lot of drums and trying to be "good" at them. And I think just naturally, there was some sort of release valve that needed to happen where it's like, ‘Oh, shit this is not fun.’ on an unconscious level and on a conscious level just being like, ‘Oh, what if I start messing around with this?’

I was also getting into recording more and more. I'd always recorded bands I was in and I was getting better and better at DAWs. I'd torrented all the stolen plug-ins I could manage to install and was just in that world of being a teenager trying to learn a bunch of stuff. And then subsequently just using loopers and samplers, where I was like ‘Oh, it doesn't have to be this linear, time-based thing’. It can be finding something, exploring that for a while, capturing it, and then working with that.

I was also simultaneously getting much deeper into listening to a lot of electronic music, more like computer music. I was always very attracted to computers. I had this weird thing where I grew up actually actively disavowing record collecting. I had my crappy, giant mp3 player that was meticulously organized and I would rip CDs from the library. I was eschewing analog hardware at the beginning for some weird ideological reasons that don't really have anything to do with music-making. And that's kind of how it started, this simultaneous interest in electronic music and also just needing a way to express myself that wasn't tied to drumming, which I was putting a little too much pressure on.

At what point did you get the idea to first start sampling YouTube? Also, to what extent do you use YouTube in your day-to-day life?

I don't really surf that much on YouTube for pleasure. I mostly use it to listen to stuff that's not on streaming services. But people were showing me weird YouTube art projects and one of them was random videos with under 100 plays. And at first, I was just watching it. You couldn't go back to one, but you can press the spacebar to go to the next one, and I just watched it with friends for hours. It makes you feel really weird, you couldn't take your eyes off it, but it was also sort of boring? There's this combination of things where it trances you out, but then something really weird happens where you're not sure what's going to happen next — like truly not sure what's going to happen, because it's not following any sort of plot device and it's not really narrating anything for you. So I was into watching them first and I don't know when I started sampling them, but I just started noticing that there's all this amazing sound on them, especially texturally. People recording shit with their phones and weird analog to digital and digital to analog transitions going on with computer audio. So I was interested in the sound of a lot of it and started just sampling, not really knowing it was gonna be for something, but I would just keep space barring until I saw cool stuff or went ‘Oh, that's a crazy sound.’ So I was kind of building that library first.

Blood Karaoke cover artwork

Your solo albums all have these really interesting frames or foundations to the samples. After talking about YouTube a little bit, did your perception of using this "frame" change over the course of making Blood Karaoke?

Yeah, I would say it did. It was interesting because I'm often making banks of sounds before I find a framework for them. And there are a bunch of different disparate threads where it's just like, ‘Oh, in this one process, I'm finding a lot of interesting stuff.’ I feel like when I'm making an album, I am waiting for some sort of unifying, abstract idea, otherwise, it's hard. It just is naturally looking for some sort of narrative aspect to it.

One interesting thing about the program you used is that it feels similar to aleatoric composition, because you’re using randomness, but it also feels like a pretty unique example of using AI in music making. Were either of those methods on your mind or did they occur to you while working?

Certainly that element of randomness. I feel especially with the computer – and randomness is just one facet of it – but what I really like about sampling is that it’s this reactive process. First, it starts by listening. You're just listening and actually trying to get in touch with that intuitive part of yourself where you're just like ‘Oh, that's interesting. I like that.’ I think that can get lost when you're really in the weeds of working in computer music because if you're editing, that's a whole different part of your brain than that intuitive side. And having something that's randomly generating something for you is such a cool way to exercise that muscle and just dive right into it, especially for me because I don't play a keyboard. So I have this thing that's spitting out something I actually have to be present for and decide what I like about it, but I'm not lost in dexterity and musicianship. I feel the way you edit something and what you choose is such a big part of your voice as an electronic musician anyway, especially because the world is sort of at your fingertips in terms of sound.

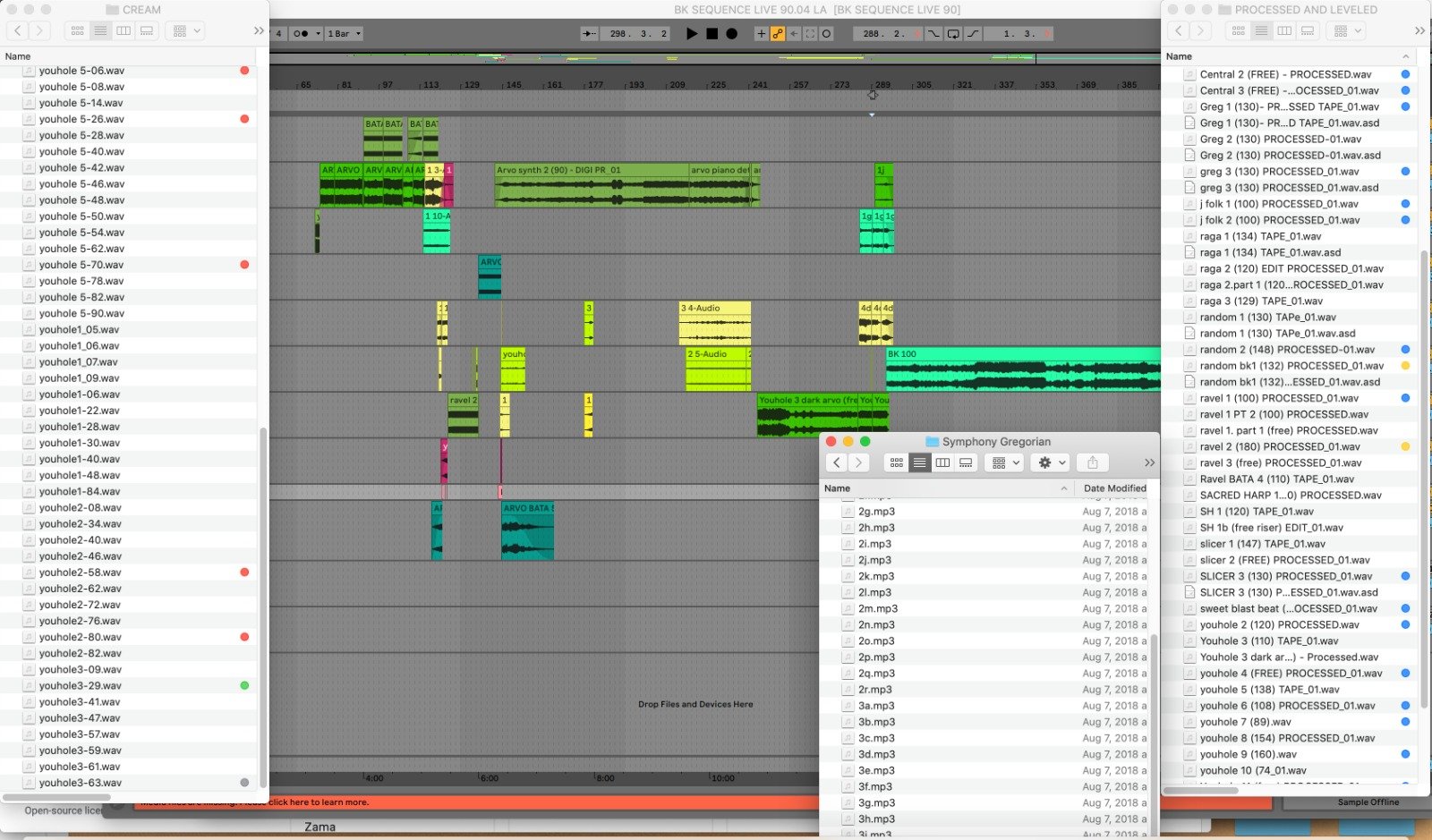

A Blood Karaoke arrangement in the making

How did you go about assembling all these sounds into a song? Were you constructing songs or editing larger things down and did you have any sort of guiding principle going in?

I was constructing little snippets and at first I thought it was going to be like a dance mix that gets faster and faster, like an alien making a dance mix out of YouTube. That was my original guiding principle. So at first, I was making beat stuff, but then there was all this other great stuff that didn't want that treatment. But I did keep going back to that feeling of ‘Make it feel like a mix gone wrong.’ So I wanted it to have sort of a warped logic in that sense of balancing and letting moments and little snippets that were interesting just be what they were and finding places for them, while also trying to have some larger ebb and flow to it. I was making all these little snippets that were really short, probably 10 to 30 seconds long, and they would have lots of samples within them and maybe some weird MIDI things. I'd be putting those together and making fun transitions and I was listening to all of those, maybe 100 little snippets or something, and at first I thought maybe the album could be this? Theoretically that sounds cool, but then I'd listen to it and be like, ‘Oh, my God, it's like too all over the place.’ It's interesting for maybe 10 minutes and then it's just… you don't remember anything, you lose it and then you want to turn it off really badly. So that was the first key, recognizing it needs a normal, breathing person feel to it, because it's gonna be overwhelming anyway and the idea is gonna come through. So I sort of trusted in that and that it'll probably be way too frantic for most people to listen to anyway, which is fine. And that was fun. That's also a world that I'm used to – an album, where it's focused on flow and stuff like what should side B start with?

Going off that, did you have a go-to signal chain for working with these samples in this way? Has that changed from album to album or do you like to kind of start from scratch?

I'd say the main thing I use in Ableton Live is just the EQ. Especially with stuff like this, where a lot of it already had a pretty processed flavor to it just from what the sample was coming from. I definitely used a lot of the pitch and warp features – I definitely got really fast at that. I also just like the sound of some of the warp artifacts and stuff like that.

That makes sense. The audio you're working with is quite raw and in some ways, that's what makes it valuable.

Totally. And I was trying to keep that too. There were some things where I'm like ‘Oh, this sounds so good!’ but then it's a little harsh, but I want it to be harsh. So it was hard to find that balance and sometimes something would just straight up hurt my ears, so okay maybe it should be quieter or EQ'd a little bit. So I was trying to keep the feel of a lot of the source material.

What do you like about working in-the-box that differs from some of your other recording methods? Obviously, you are also drumming a lot and recording and engineering and producing other people. What have you liked about that and working with the computer and the balance of those things?

That’s something I think about a lot because, especially with recording bands that are used to playing together, the computer is kind of this scary tool. Because it's just used so horribly, I think, for a lot of things. So you're aware of a lot of pitfalls about digital recording technology, in that context of over-editing, over-processing, getting way too detail-oriented on things, fixing stuff that doesn't need to be fixed. All that kind of stuff is something that, as a band, Big Thief is sort of hyper-aware of – all that shit kind of makes music sound worse, except for every once in a while. So travel with caution if you're going to start to edit a bunch of things – like, ‘Dude, no one cares if that's right, that's not what music is!’ But then also the amazing thing about it is limitless overdubbing, for that kind of context where it's about trying stuff. So I think editing is the greatest power of working in a computer in a lot of ways for me, and it's a dangerous tool. So when I think about editing in the computer, I usually want to try and think of it in some sort of creative way rather than cleaning stuff up or fixing things. That kind of editing kills me. If people get too locked into that, I just have to leave the room, I don’t care. But editing, you can use it as a super creative tool because it can free you, it can empower people to leave even more wild performances out on the floor, especially if you're a trusted editor.

I was working on this record recently and we were doing tons of drum overdubs and we had all these cool drummers in, and we realized early on, rather than have them figure something out and do it or give them direction, just have them do free-spirit takes where they're reacting to the music and they're sort of trusting that you'll get the good bits.

But I think the hardest part for me with computer music is staying with that when you recognize you're in a creative mood, to follow that and not get bogged down in something that's taking you out of it from editing to processing. Even setting stuff up sucks, like I hate all that. When I'm in the mood or when I'm producing someone and I can tell they're ready to go, I'm just like, "Please god, let there not be a technical flaw." Just plug in anything, it doesn't matter. This is the fun part of it, let's go, this is it. This is why we're here.

It's really interesting how that has influenced your engineering and things like Big Thief. Do you see those sort of sample techniques finding their way into Big Thief recordings?

Yeah I think they will more and more. There were a handful of tracks on Dragon New Warm Mountain that didn't make the album that were sort of dipping our toes into that world. And they just ended up not sounding fully inhabited, but were kind of cool. I think that kind of stuff will definitely seep in more and more. I feel like everyone's influences and curiosities continue to find a place in the band. I feel like the band is constantly shifting, trying to expand to make sure it doesn't become this thing that's so defined that we're like ‘oh, that's not Big Thief’ or ‘that sound isn't Big Thief’ or ‘that kind of song isn't a Big Thief song’. We're very conscious of how that's not a good place to be. It should be very expansive and we should be surprised by what a Big Thief thing is.

Follow James Krivchenia on Instagram and Bandcamp

Text and interview by Miles Bowe

Photo by Erin Birgy