François Bayle at the GRM studio in 1962. Photo by Laszlo Ruszka.

Looking at the history of experimental music in the 20th century, one sees that both individuals and institutions have been the main drivers of innovation, both technically and artistically. Some individuals’ ideas and techniques shaped the institutions they were nominally working for. Think of Karlheinz Stockhausen, whose name was pretty much synonymous with the WDR Electronic Music Studio in Cologne. Other pioneering figures however, such as Daphne Oram and Delia Derbyshire, went largely unheralded in their lifetimes, partly due to the fact that their work was subsumed with the institutional identity of their workplace, the BBC Radiophonic Studio.

One individual-institutional symbiosis that was crucial – even foundational – for the evolution of music in the second half of the 20th century was that of Pierre Schaeffer and the Groupe de Recherches Musicales, or GRM. Starting in the 1940s, Schaeffer formulated the radical idea of a “concrete music” [musique concrète in the French original] – a composition technique that utilizes recorded sounds as its raw materials. Today, this concept may not sound particularly provocative, but when Pierre Schaeffer began pursuing the possibilities of this collage-like approach to sound, he was both pushing the limits of the era's recording technology and, crucially, redrawing the conceptual lines of what could even be considered music.

The early years of the GRM (which was called the Groupe de Recherche de Musique Concrète until 1958) coincided with the rapid advancement of audio and recording technology in the post-World War II era, specifically, the development of the magnetic tape recorder. With its own in-house technicians building custom tape machines that could manipulate recorded sound in new ways, the GRM’s Paris studio was used by composers including Pierre Henry, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Iannis Xenakis to create new works that could only have been realized there.

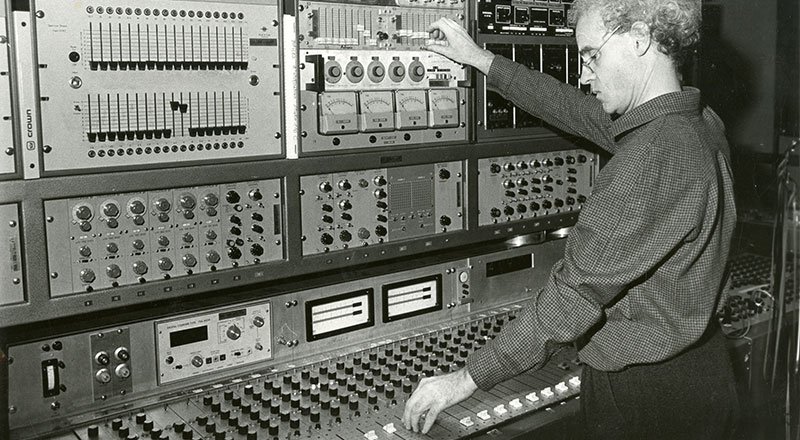

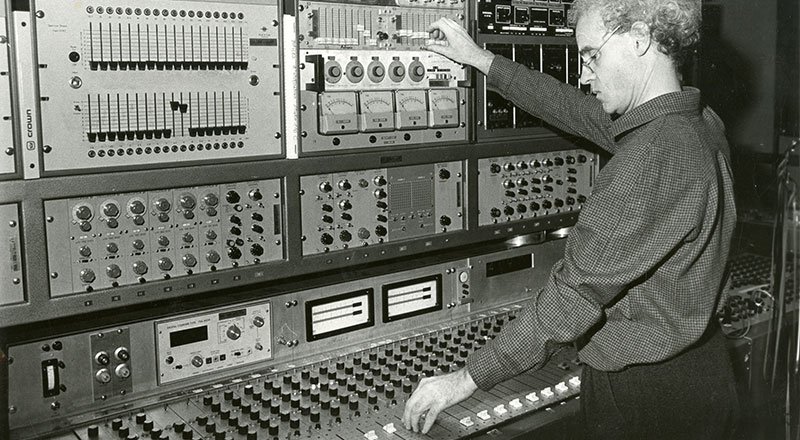

Composer Alain Savouret in the GRM Studio in 1971, which by then included Moog and Coupigny synthesizers. Photo by Laszlo Ruszka

In the 1960s, a new group of young composers including François Bayle, Luc Ferrari, Bernard Parmegiani and Beatriz Ferreyra began working at GRM and greatly expanded the range of approaches to what was then called acousmatic music, or music composed for presentation over loudspeakers. In the 1970s, GRM’s studios expanded to include an electronic studio, including a custom built synthesizer and mixing board. In 1975 GRM was incorporated into INA (France’s National Audiovisual Institue) and soon after began releasing records of some of the aforementioned composers’ works along with new pieces by Ivo Malec, Jean-Claude Risset, Guy Reibel, Michel Redolfi and others.

Throughout the 1970s at GRM a number of projects aimed at integrating computer software into the compositional process were launched with various degrees of success. A breakthrough came in 1984 with the development of Syter, a real-time audio processing software system. Then in 1992, building on some of the algorithms of Syter and taking advantage of the ever-increasing processing power of computers, INA GRM released its first commercial software. GRM Tools, as the suite of devices is collectively called, is arguably a software “classic” and remains a favorite with sound designers and composers for the sheer depth and immediacy of control that the individual plug-ins offer.

Composer François Bayle, pictured here in 1980, was the director of GRM from 1966 to 1997. Photo by Laszlo Ruszka.

We got a chance to speak with INA GRM’s current director François Bonnet about the challenges and opportunities of running an institution with such a storied history. We also discussed the changing role of music technology and where the future of experimental music might be. We’re also happy to share a free pack of over 100 samples from Luc Ferrari, François Bayle, Pierre Schaeffer, Bernard Parmegiani and others that GRM have chosen from their archives and generously provided.

One thing that would be good to know more about because it seems to be a fairly unique case and is also kind of unimaginable in an American context, is how INA GRM functions as a publicly-funded institution whose purpose is to produce and promote experimental music. For those of us not familiar with the workings of French cultural apparatus, can you explain what the GRM was set up to do and where it exists now in the landscape?

The GRM was born in the context of research into the medium of radio in the 40’s. Its founder, Pierre Schaeffer, was a polytechnician working at the French National Radio. In the Studio d’Essai [experimental studio] and then the Club d’Essai he was working with poets and playwrights to invent new forms of expression through the radiophonic medium. This research led him to theorize a "musique concrète". In the beginning, the GRM (which took this final name in 1958) was meant to fulfill Pierre Schaeffer's research around the concepts deriving from musique concrète, and especially the questions of musical perception. At the time, it was a department depending on a larger one; le service de la recherche of ORTF, France’s national public broadcaster. Little by little, GRM became a place where composers could come and work to create studies, and step by step it became a real center of musical production, offering studios, prototypes and concerts to a new kind of composer, one who didn’t need musicians but rather tape and time in studio.

Nowadays, INA GRM is still nourished by this DNA and continues in this spirit in three areas: 1) research (humanities theory and software development) 2) production (20 commissioned works every year, as well as concerts and residencies) 3) transmission, though publication and pedagogical activities.

Is the average French citizen aware of or come into contact with the GRM’s work?

It’s strange, because French citizens mostly know some GRM-linked productions without knowing GRM itself. For a long time, the jingle at Roissy Airport was composed by Bernard Parmegiani, a major figure of GRM, and a TV Show called the Shadoks (a massive success in France in 1968) was produced by Service de la Recherche and the music was done at GRM.

IRCAM, the Institute for Research and Coordination in Acoustics/Music, which was founded in 1977 by the composer Pierre Boulez, seems to have a purpose that at least partially overlaps with GRM. What is the relation between the two institutions?

Pierre Boulez and Pierre Schaeffer were two bright spirits and strong personalities. Pierre Boulez even did a study at GRM. But then, it was a time of strong beliefs and contradiction in art and the directions were rather opposite. IRCAM was using technology to extend instrumental gesture and “classical” compositional protocol (a score, some musicians), while GRM was using technology in order to compose music with sounds directly from the ear to the tapes, through a lot of different processes. Nowadays, this antagonism has faded away. We have some exchanges from time to time, mostly on technological aspects.

Pierre Schaeffer at the phonogène – a multi-speed, keyboard-controlled tape player

The GRM is notable a site of technical innovation. To what extent were the composers / group members of the earliest days directly involved in the design and construction of devices such as the phonogène and the morphophone, as well as the augmented record players and tape machines? Was there something like an engineering department that built to order or were Schaeffer and Henry themselves rolling up their sleeves and getting busy with soldering irons?

There were always technician and technical teams to release the ideas developed at GRM. People like Jacques Poullin (who engineered the phonogène), Francis Coupigny or Bernard Durr were around to help the composer and invent themselves new devices.

In its earliest form (the GRMC) and with the GRM well into the 1960s, there seemed to be fairly strict rules concerning the production of music concrète / acousmatic music without the use of electronically generated sound or synthesis. However, from the 1970s onward, the music coming out of the GRM increasingly incorporated electronically generated sounds and no longer adhered closely to the parameters of music concrète. Was this an ideological shift, a consequence of younger composers joining the group, or an introduction of new technologies (such as the Coupigny synthesizer), or some combination of all of these factors?

Somehow, in the conception of musique concrète, every sound can be used, meaning even instrumental sounds or synthesized sounds. The early electronic sounds were not of interest to the composers at the time, because they seemed somehow bland and without much expressivity. They were interesting for the WDR Köln Studio because they could be produced, re-produced and notated as parameters but for electroacoustic composers this aspect didn’t really matter. I think this changed in the late 60’s when the new synthesizers (MOOG, EMS, the Coupigny at GRM) were finally able to produce rich and versatile sounds.

The development of music-making technologies at INA GRM continues into the present day with the GRM Tools software. How and when did they get their start? Were GRM Tools conceived of as a commercial endeavour from the start?

The first GRM TOOLS came out in the early 1990’s but they didn’t just come out of nowhere. Actually, some of them were trying to go back to some early machines like the Phonogène and the Morphophone. But mostly they were continuing the first real-time treatment system developed at GRM : SYTER (SYsteme TEmps Reel / Realtime System). The Syter algorithms were really inspiring to start a collection of sound treatments as plug-ins. So as plug-ins, they were really quickly designed as commercial software, but they come from a long period of prototypes.

Bernard Parmegiani. Photo by Laszlo Ruszka.

As someone who is supremely acquainted with the GRM archives, are there some works you think deserve more appreciation than they received when they released initially? In other words, what are the GRM deep cuts? With the Recollection GRM series of reissues has there been an attempt on your part to surface some of these lesser-known gems?

There is still a lot of music in INA GRM archives, and definitely some hidden gems, but maybe more from the 80’s and 90’s now, since the early period has been well covered. But yes, the main idea of Recollection GRM was to make available records that were sold out on vinyl for ages, and being sold second hand for ridiculous amounts of money. But the second idea was to use the exposure of this new label to offer never-published music that were renowned inside the GRM but never made accessible to the audience. And it allowed us to rediscover works as well.

Pierre Schaeffer and his team at GRM, 1972. Photo by Laszlo Ruszka.

Thank you for sharing the sample pack. Even in this format, the selection of material is a good overview of the very different approaches and individual styles of the composers who have been associated with INA GRM over the decades. After the radical expansion of the sound palette and the ability to manipulate and transform sound in just about every dimension – both developments in which GRM played a crucial role – where do you see the new fields of experimentation in sound and music today?

I think the first 50 years of the GRM’s history (and of experimental music in general) were about discovering new ways of inventing sounds and building a theoretical and aesthetical framework from which the music could unfold. It was a necessary epoch, crossing technological innovations and a structuralist conceptual approach of music. But the pace of technology (which has been discarding its own previous standard every decade) didn’t allow us to have a slightly different look. It’s time to have it. Technological progress still holds promise, but we now understand that the next innovation won’t change the musical paradigm drastically. It might modify it, add something to it, but everything will not suddenly disappear with it – no more Tabula Rasa.

So we have to get over this ultimately naive modernist idea that the future of music resides only in technological discoveries. It’s time to look back and learn from the avant-garde history. And with a quick look, we can discover that there’s a huge field that is yet to explore; the field of listening itself, the relationship and differences between music and language, the status of music itself, its role and horizon.

With some conceptual tools, we will be able to find one or several desirable directions for music without having to obey to the dictatorship of technology. For example, the possibilites of AI in music is in the air nowadays. Lots of people are talking about it but it’s striking how little we think about what music actually is or should be. How can we have a valid opinion on the new possibility computer sciences offer to us as composers if we don’t think harder about the purpose of music itself? That’s one fascinating topic we are really willing to explore at GRM, in order to find the most relevant path in our R&D and software development, but also as composers and music lovers. Experimenting now is not trying every possible technological tool in order to build new sounds and new music. That was the childhood of experimental music, much needed and exciting, but still a childhood. Experimenting now is trying to find what music still can be in a world where almost everything is reduced to signals and information.

Visit the INA GRM website and follow INA GRM on Twitter.