Dudu Marote: Cultural Cannibal

Our series of articles focussing on Brazil began last week with a bit of cultural archeology when we unearthed some of our favorite Brazilian music from recent decades. Ahead of our upcoming feature investigating the country’s current crop of producers, Mark Smith talks to a figure who ties together the past and present of Brazilian popular music.

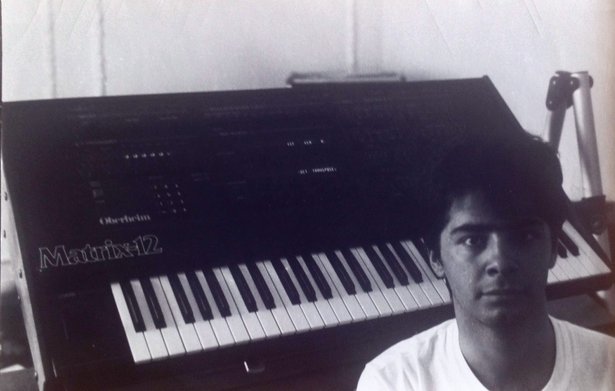

Marote with his Oberheim Matrix-12 in 1986

Despite having a population of over two hundred million, Brazil’s music scene has managed to remain something of an island. In the pre-internet era of the ‘80s and ‘90s electronic music producers created with a fiercely local mentality. In their music, one can hear the ghosts of international genres, be it house, dancehall or jungle, but these styles are merely used as raw materials to be reassembled into something altogether unrecognisable. It is music made by Brazilians, for Brazilians.

This didn’t happen by accident. Buried deep in the scene are people who have shaped the evolution of Brazilian electronic music by connecting the dots between international influences and the desires of local culture. Dudu Marote is one such figure. Marote has been riding the bleeding edge of Brazil’s electronic music scene for over two decades. Whether he is fusing bossa nova with drum & bass or breaking dancehall into pop music, Marote has been the brains behind several key innovations that are still shaping Brazilian music today. We talk with him about the milestones in his career and the production techniques that keep him inspired.

You’re credited with producing Brazil’s first ever hip hop album. What was Brazil like as a context for music making when you were starting out?

I’m totally from São Paulo. It is a huge city, a complicated city. We’ve got a metropolitan area with over 20 million people, so it’s like a Chinese or Indonesian city in scale. Huge. Totally messy. But it really vibes at the same time. São Paulo has parties every night, loads of things happening, all kinds of music. So I was born in São Paulo, always lived here. I started as a musician in the ‘80s. I’m 49 now. I got my first synthesiser when I was 15, in 1980. It was a Yamaha CS 5 and the good thing was it had no memory. So I had to learn it, all the oscillators, filters and modulators when I was 15. When I started as a music producer I produced the first Brazilian hip hop album. So yes it is true, that was the first hip hop album made here. It was very naive. We were kind of reflecting what we were receiving at that time in 1989. In Brazil at this time we didn’t even have MTV; that started here in 1990. No Internet either obviously. So we would see little bits of Run-DMC stuff, Public Enemy and we’d reflect those things with the Brazilian reality. At that time I was working with an Atari ST, Notator, and loads of samplers.

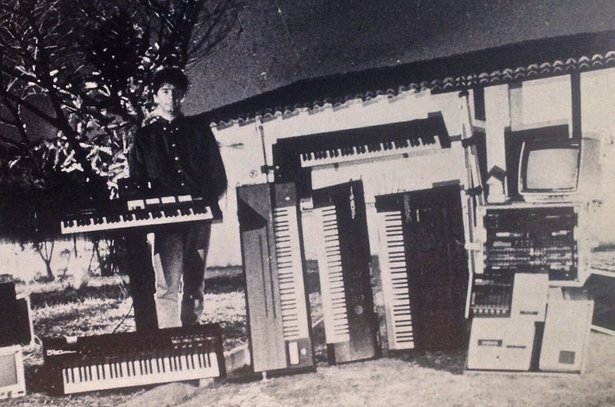

Marote’s studio collection in 1987

And that led me to produce what some call the first dance music album in Brazil. It was a band called Que Fim Levou Robin. That was a mix of technotronic and Brazilian fire but the lyrics in Portuguese were very pushy and they really helped the gay scene through the prejudice that was around in the early ‘90s.

But from the beginning you were always involved in more than merely producing music.

At that time I was working with Roland. So I’d have access to all the new keyboards like the D50, the samplers. When they released the S-760 and S-770 samplers they made some Brazilian libraries. They got me to help them with that. I was involved in compiling those banks. I was with the son of Ikutaro Kakehashi, the founder of Roland. He sent his son to me and we travelled around to other cities in Brazil to record traditional sounds for Roland’s samplers. And by 1990 I had this guy called John Klein who used to work at MTV London. He was from America, and he came here to create MTV Brazil and I was working on setting that up with him. And I did the music for the first MTV video clip in Brazil.

Another credit to your name is the introduction of dancehall rhythms into Brazilian popular music, a combination that is now pivotal to what we think of as the ‘Brazilian sound’.

I went to my first rave in Kingston, Jamaica. It was called a Dancehall Ragamuffin rave, in 1993. At that time there was this kind of electronic music happening – it was happening in the UK, India and Jamaica at the same time. It was called bhangra. This was before jungle happened. Some people called it dancehall as well but it has its origins in India. I really loved those things at the time. But I was involved in this dancehall and after going to this big rave in Kingston I really got into that sound.

Then I met some other Brazilians they liked that sound as well... they were this band called Skank. They were just starting but we had the same vibe. They wanted to use this sound but they didn’t have the best techniques to do that. It could sound better so I - as a producer - got involved with it. I did a remix for one of the tracks off their first album with a Jamaican friend. We did it off the first wave of when jungle was pushing overground, just after the Prodigy was big with ‘Out of Space’. The name of the track we remixed was ‘Baixada News’ – and that’s the jungle remix. And then Skank loved it so when they went to do their second album, Calango, they called me in. And then I went to Rio to one of the best studios in Brazil called Nas Nuvens, which means ‘in the clouds’, and I was there for two months totally focussed on this album. It’s very dancehall it’s very reggae-ish but the result is very Brazilian. It’s a mix of Brazilian vibes with reggae and dancehall but very electronic. It was released July 1994. It sold 1.2 million. If you compare Brazilian market at that time to the US it is the equivalent of selling 10 million. It had six radio hits. It was huge.

Mixdowns in the studio with Skank in 1996

After this you went through a phase with drum & bass before finding a home in house music. It seems like you take outside influences, apply them to your context then move on to the next point of inspiration in a methodical, regular fashion.

In Brazil we are like cannibals. Brazilians are like cannibals in culture – we eat and then we regurgitate. Everything we did was always like that. Eat, digest and regurgitate in our own way. Drum & bass with bossa, dancehall with Brazilian vibes, whatever – so we started to do some house music with some funky stuff, fuse it with some Brazil vibes, but not Brazilian vibes musically, Brazilian vibes lyrics-wise. Because for us now in 2014 lots of Brazilians speak English, but not at that time back in the ‘90s and early 2000s.

For us it is important to reflect our realities through language into the music all the time. We want to be involved with everything – that’s why we make our version of things, but not caring too much what people will think about it outside the country. If people love it outside, awesome; if they don’t, awesome, not a problem. Brazilians don’t have this thing of ‘oh I have to make it in Europe, I have to make it in the US’. The UK, US, Australia, Canada, they all have some sort of connection. Brazil, we don’t have any connection. Brazil is about Brazilians. We could kind of have some connection with Portugal, but we don’t. Brazil is just Brazil.

Marote with his modular in 2011

What is exciting you about production now? After two decades do you still consider yourself a student of sound?

Right now I’m very much into distortion. I’ve just been to France to attend a Mix With The Masters course. I’ve been to study with Tchad Blake who is the Black Keys and Arctic Monkeys engineer. He is a genius. I was with him for a week and another fantastic engineer called Manny Marroquin who works with Kanye West doing mixdowns.

These guys have techniques that you can apply to all kinds of music. This is when I got into this idea of using less reverb and more distortion. Using distortion instead of reverb, thinking of distortion as ambience. Using compressors to give character, not just to compress. Like using an 1176 to give personality. You know, crank it up to make it sound like when you get a basketball and drag your nails into it, that crackling, tactile feel – that’s what I’m into right now.

Live set from VCO Rox, Marote’s latest project

That’s an interesting concept, using harmonics to connote a sense of space rather than shaping a reverb plug-in which can’t help but sound like an artificial model of space.

This is something very important for me. Another thing I’m constantly crazy about is nailing the groove of things. Any artist I work with, no matter the instrument or the take, I’ll be moving everything. I’m nudging those clips around all the time – not always warping but just shifting the phrases. I think after 25 years of hip hop culture in the world, its influence, its groove, is inescapable, even if you’re not making hip hop. It is part of everybody, like rock is part of everybody.

VCO Rox on Boiler Room playing over ‘Onda’ by Joutro Mundo

So when hip hop came in huge it changed all the groove of pop music. This started being applied by people like Michael Jackson. For instance, not everyone realises that he sings a little off the pulse, he’s not too tight on the downbeat. To make music connect to the language of the culture of the world you have to nudge things all the time, every musical element, constantly pushing. You’ve got to get everything locked up, but when I say locked up I don’t mean quantized. Quantized is just the beginning. When I warp I don’t even think about quantizing, because there is no ‘right’ groove for any track. The right groove is what you physically feel is right at that moment. And one day after it can change. So you have to always be sensitive to it and keep looking for the balance.