Composing Infinity: Max Cooper on his New Album

Photo: Alex Kozobolis

Electronic producer and visual artist Max Cooper has never lacked curiosity and ambition. By now, it’s well known that Cooper studied computational biology, and briefly worked as a geneticist at University College London. But the music bug bit him back in 2010, and Cooper fused his intellectual curiosity for science and technology with the vast sonic and expressive potential of electronic music. The London-based artist’s 2016 album Emergence, explored occurrences in nature of individual parts coalescing into a unified whole – such as the murmuration of starlings – and paired each song with a music video that described an emergent phenomenon through data visualizations.

It was with Emergence that Cooper found his preferred format – the audiovisual album. For 2018’s One Hundred Billion Sparks, each track on the LP is a score, as Cooper described it upon release, to a “story stemming from this system of one hundred billion sparking neurons, which create us.” For his latest project, Yearning for the Infinite, Cooper delivers another high-concept audiovisual album. Commissioned by The Barbican Centre, a performing arts institution in London, Cooper’s latest multimedia project examines the human impulse to want, build, dream, and fight endlessly.

As a musical document, Yearning for the Infinite sits comfortably next to Cooper’s previous ambient techno and IDM outings, but with a vastness befitting the title. There is also a notably new degree of improvisational depth. The intro track, “Let There Be”, heralds Yearning for the Infinite’s sonic expanse, with chord changes, moods, and textures that recall Boards of Canada’s Tomorrow’s Harvest, as well as the ambient electronic work of both Vangelis’ (circa Blade Runner) and Jon Hopkins’ Immunity. The album alternates between extended washes of sound and the seemingly random synth sequencing of tracks “Parting Ways” and “Perpetual Motion”– tunes that have deceptively simple melodies and beats, but which Cooper ornaments with detailed sound design and rhythmic one-shots that musically fit the narrative of humanity’s constant movement and development.

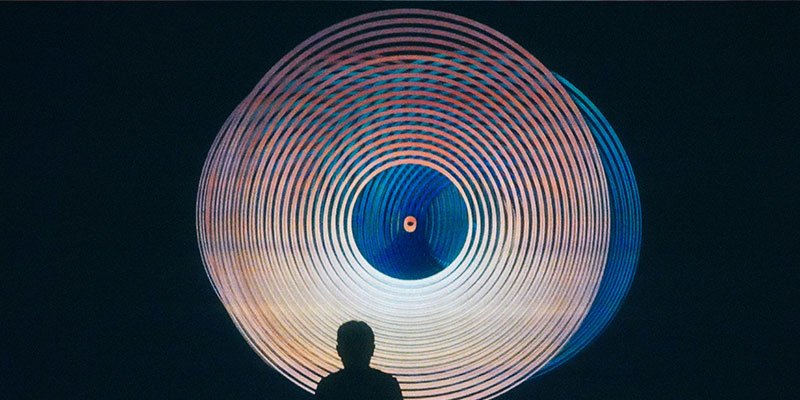

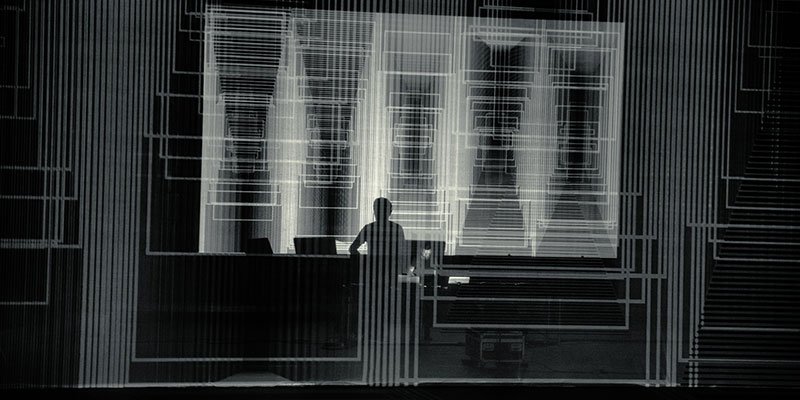

While Yearning for the Infinite can, in typical Max Cooper fashion, be experienced through collaborative music videos, or simply as a music album of music if one prefers, he recently debuted the accompanying audiovisual show at The Barbican and will subsequently take it on the road. From his perch, using a Lemur touchscreen interface and APC40 as his controllers, Cooper fused sound and visuals from a laptop running Ableton Live and Max for Live, which sends MIDI messages to two other laptops, each running Resolume VJ software. At the premiere, the audience was treated to video from eight screens – all synced, controlled and effected by Cooper’s live audio performance.

Over a recent phone call, Cooper told us that oddly enough, the idea of “yearning for the infinite” had its roots in a more reductionist method. Indeed, Cooper went “downwards” to find the “big thing”.

“Barbican has this program for the year called Life Rewired, which is a series of events around new technology and how it influences and counter-influences society,” says Cooper. “They sent me this document about the concepts they were interested in, and there were wide-ranging topics within it: biotechnology, crypto, fin-tech, geo-engineering, and all sorts of other science-related, society-impacting stuff. They asked me to come up with an audiovisual project based on it.”

Crafting an entire album and A/V show out of a brief for a single event was a first for Cooper. And he is unaware of any other musical venue or arts institution where this type of audiovisual project could happen within the context of a musical approach. Cooper knew the hall where he’d be playing at the Barbican, as some of his favourite gigs had been held in the same place over the years. As such, he knew it was a beautiful space, which could be used as a canvas itself.

“In general, I’m very much into using natural surfaces for projection in addition to screens,” says Cooper. “The idea being to turn the whole space into a moving structure which engulfs the audience. I always want to bring the experience to the audience rather than have the performance as something they watch from a distance. I’m much more interested in a beautiful shared experience where we all get something of a personalised show, and it does look different from every perspective.”

Cooper boiled the brief down to its essence, deciding to explore “the human yearning for progress, knowledge, war, and growth – this thing many people in Western society are reared to pursue life in that way.”

Photo: Alex Kozobolis

“We set goals and are hoping our favorite team wins,” Cooper says. “We’re always chasing these goals that are essentially unreachable… The way I’ve been productive in making my visuals in the past has always been this searching for the building blocks of whatever the concept is – finding some process I’m interested in, some system, and trying to boil it right down to the building blocks and visualize them.”

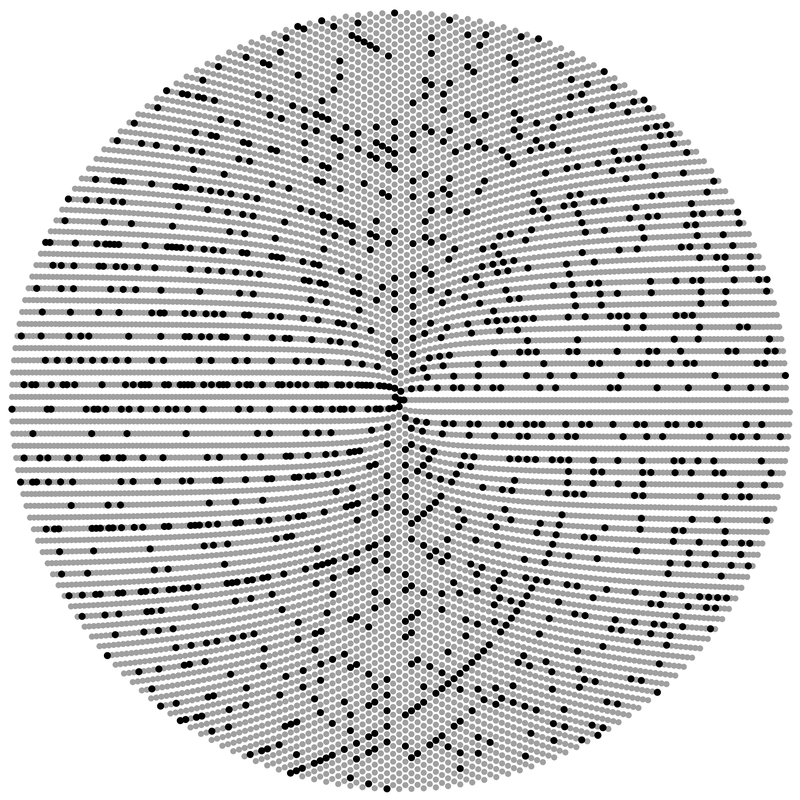

For Cooper, the most basic units of any system he can find tend to be both simple and beautiful, as if nature is built of “special components with maximized compression of complex reality data into simple programs”. On Emergence, for instance, this lead to the Sacks spiral imagery, a graph that shows the distribution of prime numbers; although he was also interested in symmetry as examples of some of nature’s most fundamental structures. In the One Hundred Billion Sparks project, Cooper explains the main inspiration was Rule 110, a cellular automaton that is a fundamental aesthetic of universal computation.

The Sacks spiral shows the pattern of distribution of prime numbers.

“These are all simple systems, but they all contain a huge amount of visual richness, and for me they are more meaningful than more recognisable everyday scale imagery,” says Cooper of his projects, including Yearning for the Infinite. “I feel like I get a little glimpse into the depths of nature with these more quantitative visualisations, the artistry not coming from the human animator so much as from nature itself. I find that really interesting.”

On Yearning for the Infinite, Cooper’s simple-but-beautiful perspective was calibrated for the Anthropocene; the geological period we’re currently in characterized by humans’ endless remaking of the natural world and themselves. Cooper found himself attracted to the idea of trying to find ways of visualizing the idea of the infinite. He knew it would need to be shown in terms of its expression in human nature: the endless toil and push toward growth. For Cooper, this is just what humans do as a species.

“There are some simple ways of visualizing the infinite, like the parallax in art,” says Cooper. “There is the infinite in the human nature side of things, which isn’t literal, and then the more literal, technically-describable, explicit visualizations of the infinite. And I set them off against each other and try to tell this story of human nature.”

To realize these visuals within the music hall, Cooper suggested a projector and screen-layering format to The Barbican, which he says hasn't been used before in the space.

“There are all of these abstract visualizations of the infinite, and then there are all these humanized stories of these people in the city, or walking forever or on their bikes, people doing what people do endlessly,” he adds. “The whole show combines the two bits of footage. Sometimes it has whole chapters of one or the other, but later on in the show it starts to layer the two together, so you get people living inside these abstract infinite structures and being aware of it. ‘Perpetual Motion’ comes later in the show and it starts to integrate things from other videos.”

A Collaborative Story

Though Cooper is a recording artist, Yearning for the Infinite demanded he become a storyteller, artistic director, and film composer. Each song is a chapter, with every track paired with a different type of visualization. As Cooper describes it, he scored music for each chapter of the overarching story.

To produce the visuals, Cooper collaborated with a range of specialists including animators, visual artists, mathematicians and data scientists – mostly people he’d worked with in the past. “There was a give-and-take on both sides,” says Cooper of the collaborative process on Yearning for the Infinite. “Sometimes we had a chapter for which I’d written some music, and then we realized the music wasn’t right. So, it was a flexible collaborative process. But, on the whole, the music was scared to this imaginary film, and the visuals mainly came later.”

To create the music for this imaginary film, Cooper had to represent the themes with a variety of sounds, textures, rhythms, sequencing, and editing. On the track “Repetitions”, Cooper took on the “boring repeats within repeats”.

“I was just trying to find different principles that I could apply that would be representative or somehow reflective of this idea of the infinite, and repetition is an easy one,” he says. “With repetition, just don’t stop, and you’re off to the infinite. But, the challenge was to make a repetitive piece of music that wasn’t totally dull but still engaging.”

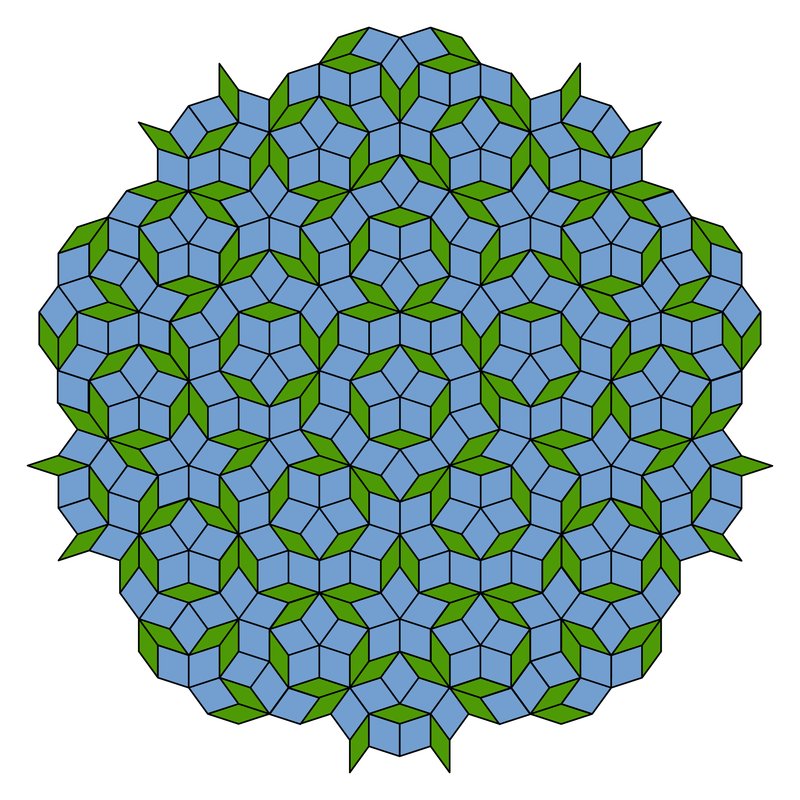

Cooper also looked to Penrose tiling for inspiration. Invented by mathematician and physicist Roger Penrose, it is a system of aperiodic tiling with geometric properties, and is self-similar (can be inflated and deflated, like fractals). With Penrose tiling, the tiles are always changing on an infinite plane without repeating. To musically simulate Penrose tiling, Cooper set out to create an aperiodic piece of music. One technique he used was to make all loop lengths prime number multiples of the same value.

Penrose tiling consists of simple shapes that can cover an infinite plane with neither gap nor overlap, without the tiling pattern ever repeating itself

“If you have multiples of a prime, they never meet any other multiples of any other primes because, by definition, they are the building blocks that cannot be broken down into smaller units of numbers: they’re only divisible by themselves and one,” Cooper explains. “And because these building blocks never overlap, you get this non-repetitive syncopation. So, you can have a piece of music that never has the same loop twice, even though it’s all loops, just like Penrose tiling with the non-repeating geometric shapes.”

Photo: Alex Kozobolis

“There were really interesting ones like that, where I could quite really explicitly put the ideas into the music,” he says. “But then there were some where I was just like, the video is going to be about how you can get infinity by constantly branching structures. For that, I knew the aesthetic of the video, and the scoring was an improvised freestyle to what I knew the visuals would be.”

And, for the first time, Cooper used improvisation as a technique for suggesting infinity. By definition, he could not fully express infinity, so he reasoned that perhaps he could improvise with his sends while thinking of this “endless space”.

When improvising live, both in rehearsals and for the performance of Yearning for the Infinite, he used techniques like circular morphosis, where there is no time signature and the playing is quite free. And when there is a time signature, such as in the chapter “Parting Ways”, it doesn’t keep to the 16 or 32 bars. Instead, it deviates from those structures, both rhythmically and melodically.

“It gives everything a more organic, melting feel,” says Cooper, “which seemed to be appropriate for the product and gives it a nice sound.” For Cooper, the improvisational character of Yearning for the Infinite sets it apart markedly from previous albums and audiovisual projects.

“I’m not really a musician, as in a live musician, and I’ve never been able to play the keys properly,” Cooper says. “After years of playing badly and messing around, I’m starting to get proficient enough where I can actually do live patch design and live playing, and trying to improvise things around the ideas and the visual aesthetic of the chapter I was working on at any given time.”

Designing Infinity’s Sound

To design the sound of Yearning for the Infinite, Cooper used both a trusted synthesizer and a new machine. He says most of the album was made using a Dave Smith Instruments Prophet 6, an analogue synth that builds on the iconic Sequential Circuits Prophet, and the new Moog One polyphonic analogue synthesizer. The Prophet 6 has been Cooper’s go-to synth over the last couple of years because of its ease-of-use and his familiarity with it. As he recalls, it got a bit more use on the album than the Moog One.

Cooper also used another old standby, a Moog Minitaur, obtained years ago while playing shows in in San Francisco. At the time, Cooper’s setup was mostly digital, and he thought he should get an analogue synth. So, he settled on the Minitaur.

“It doesn’t do that many different things, but what it does, it does beautifully,” says Cooper. “It features on all of the tracks for these nice Moogy bass stabs.”

Photo by Michal Augustini

Beyond synthesizers, Cooper is an admitted pedal fanatic. Lots of delays and distortion effects populate his board. For extreme coloring of sound on Yearning for the Infinite, Cooper used a Fairfield Circuitry Meet Maude analogue delay, and a Moogerfooger MIDI MuRF (Multiple Resonance Filter Array). To destroy his sounds, Cooper often turns to a WMD Geiger Counter, a pedal with no wet-dry signal with a wavetable modulator that can do everything from a bit of gain to glitchy and lo-fi degradation. Indeed, Cooper has a thing for noise.

“One of my favorite noise pedals is the Industrialectric RM1N [Reverb Fuzz], and it gives some really extreme feeding back chaos,” says Cooper. “I use the Strymon Blue Sky for a lot of the reverbs, and I just love the plate reverb on it, and then of course the Roland Space Echo. But, I also like the Strymon El Capistan – the emulation tape echo is pretty good as well. I’ve also been using the Metasonix F1, which has a couple of valves on it that get nice and red and make distortion.”

Endless Editing

All of the improvisation left Cooper with hours and hours of recordings. As always, detailed and extensive editing was required to shape Yearning for the Infinite’s sounds into individual chapters and a cohesive whole. For every minute’s worth of audio on the album, Cooper estimates that there is an hour of recording.

“The way I write my music is very messy, partly because I’m not good at playing, but more so that I love semi-generative approaches,” Cooper explains. “If I’m jamming with a synth, I’ll often have random waveform LFOs assigned to certain parameters on the synths I’m playing with.”

Cooper considers the LFO a very underrated tool for randomizing sounds and rhythms. He needs that element of unpredictability. “When you get that balance just right between something you can control musically but it has a life of its own,” says Cooper. “It’s really a beautiful thing.”

Photo by Michal Augustini

Making semi-generative systems that he can control and play to get what he wants occupies a great deal of Cooper’s time. Much of this can be done in synth patch design with random waveforms and modulation options, but Max for Live control devices are also critical to both his recording process and live performances.

“Max for Live control devices allow you to randomize parameters, make them wander within certain boundaries, or link one parameter to another,” says Cooper. “Max for Live allows me to start setting up these complex webs of wandering that will wander within a box that I deemed musically likely to be good, although I’m never quite sure.”

“I really like the possibility of being able to introduce enough chaos,” he adds. “I’m always in search of this liquid timbre approach – it’s something I’m pushing for with each album, but I still haven’t got there quite yet.” The goal, according to Cooper, is to make sounds whose timbres flow and morph in interesting ways.

To that end, Cooper spends a great deal of time playing with hundreds of layers of audio. Most of the layers are composed of the aforementioned little synth wanderings, or “semi-generative messy sound design weird noise things”. Cooper edits each down and fuses them to get hundreds of layers of small one hits.

“There are tons of sounds that you will only hear once on the album,” says Cooper. “I just love finding little surprises in there when you listen to again, there are always these micro-rhythms and micro-structures and hidden stuff. I love that aesthetic, and it’s something I’m pursuing more with each album. It’s a really interesting path.”

Keep up with Max Cooper on his website and Soundcloud

Interview conducted by DJ Pangburn, a multimedia journalist, electronic musician, and video artist based in New York City. DJs, records and plays live under the name Holoscene.

Check out his tunes on Instagram and Soundcloud