Sounds Outside: The Art of Field Recording

One of the underlying themes of the Loop event in Berlin last November was to examine some of the many ways producers relate to sound in their environment - whether it was Holly Herndon’s internet-inspired digital utopia, Matthew Herbert’s discussion around his musical manifesto or AGF’s workshop on field recording.

In its broadest sense, ‘field recording’ refers to the process of capturing sound outside the controlled confines of a studio. Within that definition however, a world of differing processes, theoretical approaches and outcomes are found. From Pierre Schaeffer and the Musique Concrète movement of the 1940s, through to the representation of ‘exotic’ ethnomusicological recordings, environmental documentaries, and the presentation of natural soundscapes as music – the term covers a lot of ground and has generated its fair share of debate. What ties these elements together is a sense that there are different ways to listen to our world, and that listening involves numerous aesthetic, political and social considerations.

Field recording today is growing in popularity, both from audiences seeking more diverse listening experiences and by artists looking for environmental sources as compositional tools. Affordable music technology has made the recording process more accessible and the results infinitely manipulatable – it’s easy to see why the approach can be found across a wide spectrum of electronic and pop music. As a process and a practice, field recording crosses over into natural history, eco-activism, and zoomusicology – the study of non-human music and the subject of a fascinating recent book and CD. In this article we touch upon some of these elements and chat to Chris Watson and Yannick Dauby, two of the leading artists in the field.

In The Field At Loop

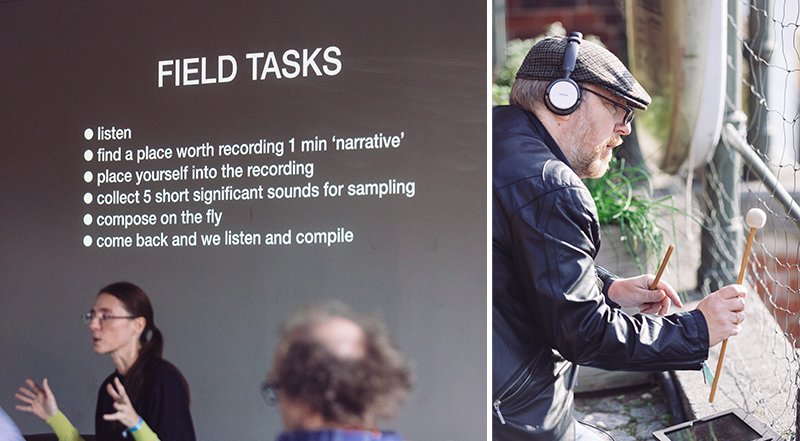

AGF’s field recording workshop at Loop 2015

AGF (Antye Greie-Ripatti), the acclaimed producer and multi-disciplinary artist touched on many of these themes in her Loop workshop. Drawing on her own experience as an musician, and her growing lack of interest in pre-recorded samples, she revealed how capturing sounds from her environment became an essential part of her creative process. Integrating her love for natural environments with her passion for technology, AGF and her partner (fellow electronic pioneer Vladislav Delay) moved to the island of Hailuoto in Finland, where she could develop a more direct relationship with sounds found in nature. Her work now often involves carrying synths and samplers into remote locations and recording and composing with her environment as a key collaborative force. At Loop, the participants of the workshop were asked to walk around Berlin capturing sounds and bring them back to the studio to use as compositional building blocks.

AGF’s approach to her own work and her workshop falls into the discipline of field recording that involves manipulation of the recorded sound, or the addition of instruments and processes from outside of the original recording environment. Some practitioners within the field have previously approached the discipline in a more documentarian fashion – attempting to capture and represent a ‘true’ experience, or as Australians sound artist Lawrence English puts it, “a mechanism through which objectivity could be transmitted”. This has been one of the central, and most debated dichotomies within the field.

Today, it’s clear that some of the key releases and artists active in the scene have connections with both sides of this divide – environmental recordings as both a documentary process and an artistic endeavor – and that the lines are increasingly blurred between the two. Recordists such as Bernie Krause, Hildegard Westerkamp, and Chris Watson all have links with the avant garde, but their body of work also aligns them with environmental soundscapes and ecological documentary. As highlighted by AGF, Chris Watson, formerly a founding member electronic experimentalists Cabaret Voltaire and Hafler Trio, has perhaps become one the leading exponents of field recording as artistic expression.

Documentation vs. Composition

Chris Watson’s work has encompassed natural history documentaries for film and TV, and his development as an artist has moved from his early documentary work to more edited, processed and filmic narratives – sounds recorded from habitats and locations where it’s impossible to place one's ear, such as inside melting glaciers, deep under sand or the ocean.

Watson explains:

“[My approach] did expand and change direction a bit. I didn't regard the first pieces as pure documentation; I thought they stood as pieces themselves, and really there was nothing I could do to improve on that; I saw them as really quite sort of perfect "compositions", which came about through a process of documenting sounds. Then as I changed my recording techniques I began to hear individual aspects that I hadn't really heard or appreciated before, that really defied any sort of human-compositional techniques, so I became interested in just engaging with those and that's why the compositional technique for records like Outside the Circle of Fire was simply the microphone technique itself - that became sort of the main instrument, which was a change from Stepping into the Dark which was more atmospheric, more ambient, more recordings of space.

As a teenager I was interested in musique concrète and I became fascinated by some of the contemporary composers of that time like Karlheinz Stockhausen, Olivier Messiaen and Pierre Schaeffer... I realised that what I was listening to could be regarded in a musical way and could be used as tools for composition in a more satisfactory way than I could contrive in the studio.”

The notion of presenting an objective reality is one that has being widely deconstructed over the years, and the idea that the recording technology itself, the positioning of the microphones, the choice of when to begin and stop recording, are all compositional decisions that infer each piece with a sense of artistic agency. In an illuminating article for FACT Magazine, Lawrence English points us towards a conversation with Chinese sound artist Yan Jun:

“There is no such thing as documenting a reality. There is no divide between documenting and creating. The point is I don’t build dreams neither by field recording nor by playing my electronics instruments or computer. To choose equipment, choose position and push record button are acts of composing.”

This view is shared by Yannick Dauby the Taiwan-based French artist whose output merges field recording with synthesizer improvisations.

Yannick Dauby at work in the mountains of Taiwan

“No matter if I'm outdoors doing some recording or in the studio editing sounds, I'm finally listening to transducers – loudspeakers or headphones turning electricity into air waves. Any sounds I'm working with has been mediated by audio technology. Therefore, I don't think I'm dealing with any "pure" sounds, they're all inhabiting a medium. Then, according to different projects I am navigating between two extreme considerations for sound : documentation or abstraction.

Sometimes, I am invited to work with communities, or to document some natural area, I would try my best with field recording to share my own perception of these sounds. The decisions made in the field (which microphone, when and where to record), the selection of the material, the tiniest transformation by equalisation or removal of unwanted sounds are all strong choices of altering the original signal recorded. There is no neutral (or pure) documentation, it all reveals a perspective, a subjectivity, a reconstructed reality.”

It’s interesting to note that this a relatively new position, and that the history of field recording has strongly tended towards recordist as archiving / documentation, such as the ethnomusicologist expeditions of pioneers such as Hugh Tracey, or the plethora of “Sounds of the Serengeti” style LPs in the 60s and 70s. Lawrence English argues that “the conditions of the digital age, travel opportunities and the abundance of access to just about anything” has meant that these sounds, once outside the realm of most people's normal existence, are redundant, and often even culturally “toxic” – a remnant of a eurocentric worldview that exoticises the ‘other’. As a result, English suggests that “we seek new perspectives and exposures that refocus sometimes even the most commonplace experiences into profound and provocative listening situations.”

What Makes A Field Recording ‘Work’?

Chris Watson’s piece transforms a recording of insects in Borneo into a spectral drone

What’s clear is that there is a great deal more to producing an engaging piece of work than hitting record and wandering into nature, and it’s interesting to see how Yannick Dauby and Chris Watson view ‘success’ or ‘worth’ in terms of their recordings and releases. As the parameters and frame of reference for listening to these sound collages are quite distinct from how we relate to much music / recorded sound, a different set of criteria emerge. Watson elaborates:

“Because I'm a sound recordist, it's what I remembered from the location where the recordings were made. It's a method of extraction I suppose, in order to produce something that I can remember, almost like a memory effect. It's my recall of memory and feelings about the sense and spirit of that place that I try and reconstruct in my compositions. It’s somehow a very traditional way of composing: Sibelius was inspired by the forests of Finland; Messiaen by the bird song in France. So it's a well-trodden path and it's something that I find particularly inspiring because I enjoy being out recording and it's a way of representing that place. And the process in that sense is intuitive but it's inspired by my recordings from that place. The great thing about sound is that sense of recall with that. I'm sure if you ever done any recordings, as soon as you hear it you are taken back to that place. We have such a powerful memory for sound. I use that a lot in my work.”

"The great thing about sound is that sense of recall... we have such a powerful memory for sound. I use that a lot in my work."

Yannick Dauby also sees the process as one that interacts with memory of a place, but also finds a potential political dimension:

“I always try to keep myself extremely humble about field recordings: I just found myself in some situations and I am trying to extract some audio traces from it. I consider my role as an active listener and as someone who will deal later with the fixed memory of this listening.

Listening without any judgement or comment might be a political proposition. Just a little bit of attention sometimes changes things. Presenting and sharing sounds of environment, an endangered species, a threatened ecosystem or a dying cultural practice, of course have some effect on the audience, but most of the time it would require bringing the contexts of sounds, telling stories and use the listening to engage a discussion or a reflection. In some aspects, it is a work which is not unrelated to composition.”

Watson recalls having recorded thousands of hours of unusable material, that somehow fails to transcend or translate to a wider audience and is never released. However, one of his most well regarded works, El Tren Fantasma, recorded on a 5 week train journey across Mexico, has clearly connected with many people.

“The pulse of railway is similar to a heart beat and that must be one of the first sounds we hear before we’re even born. We’re 16 weeks in our mother’s womb when we start to hear or are exposed to the world of sound, diffused through amniotic fluid. It’s my theory that we find sounds like the railway sounds so absorbing because it replicates a heartbeat.”

A fundamental part of my work is to try and recreate that sense of excitement of being out there, listening to things in the real world and being able to come back and present it in a way that people can relate to. That’s the great thing about sound; it doesn’t need any great artistic justification. People get sound very directly. It strikes into our hearts and imaginations in a very unique way.”

Animal Music

The recently released Animal Music book and CD (Edited by Tobias Fischer & Lara Cory) examines the relationship between the animal kingdom and human perception of musicality. A series of recordings from around the world, undertaken by Francisco Lopez, Yannick Dauby, Jez Riley French and others asks us to consider the notion of animal spirituality and aesthetics. Are bird sounds merely codes for expressing sexual status, predator warnings, food availability and so on? Or are there elements that transcend biological necessity and express something more? Ornithologists have observed that accents, rhythms and grouping of sounds change from location to location amongst same species, perhaps suggesting that cultural factors exist and influence bird song - something also observed with sea creatures such as dolphins and whales.

If this is indeed the case, what does this mean in terms our relationship with the animal world, and does the possibility to communicate with animals exist as a result? Chris Watson believes it's an interesting but ultimately fruitless avenue.

“What people like David Rothenberg are doing is interesting, but it’s the frequency domain and the dynamics within which these animals exist that makes communicating with them difficult. Animals have been on the planet a lot longer than we have, and have had much longer to evolve sophisticated communication techniques. We might be able to transmit and receive information, but I think it’s pushing it to say that we can communicate effectively with these animals. I think it’s quite dangerous. Can you imagine what the world would be like if we knew what insects were saying? I mean, we can’t even understand each other, so what hope have we got in trying to understand different species?”

“We have this very arrogant notion that we’re top dog in the animal world. We’re patently not. We can’t understand the sense of communication in the animal world, we can dip into it, in our very restricted frequency range, but we really have no idea what’s going on.”

Gibbons in the Cambodian jungle sounding remarkably synth-like

Practical Matters

Field recording as a subjective artistic expression is entirely entwined with the technological developments of the equipment used to record. The recording expeditions of the 40s and 50s involved huge, cumbersome equipment that leant itself to more ‘documentary’ style ethnomusical projects - presenting ‘sonic obscurata’ from around the world. The development of highly portable, and relatively affordable equipment has opened up the possibilities of the discipline to a wider range of participants, and made previously inaccessible audio worlds explorable. The internet has a number of helpful sites that break down various techniques for recording and provide equipment recommendations:

Chris Watson also has some useful practical tips: “Well obviously you have to be prepared for your environment… because if you're cold, wet and uncomfortable then you're not going to record. One of the things I'm most interested in doing is getting away from the microphone, creating some space between myself and the microphone. I do very little recording where I stand there holding a microphone, because with my work, if it's wildlife, nothing comes close. I'm much more interested in getting microphones into places where you wouldn't ordinarily want to put your ears, so we're putting microphones in the middle of bushes and thorn bushes. Make sure you're comfortable with your recording environment; make sure, if you're going out 03:30 in the morning, that you can operate your equipment in the dark. Make sure you get a recorder you can operate with gloves on. Practical things, but the main thing I think is useful in achieving something different is to get away from the microphones.”