Yuri Suzuki: Designing with Sound in Mind

From sound installations for some of the world’s greatest museums to DIY musical instruments, Yuri Suzuki’s creations combine intricate design with maximum accessibility. “My practice is social engagement through sound,” Suzuki explains. “I focus on the experiential side of things.” This could mean fashioning a horn sculpture that uses artificial intelligence to learn from singalongs with museum visitors, making a consumer-ready record lathe that enables anyone to cut their own vinyl discs, crowdsourcing audio for a planet-spanning sequencer, or turning a globe into a spherical record that plays back the sounds of the earth.

The Sound of the Earth – Yuri Suzuki`s spherical record project

Suzuki initially studied industrial design in Japan and looking back, it’s now easy to see that influence across his entire body of work. In the years since moving to London to attend the Royal College of Art, he has established himself as one of the world’s leading visionaries working at the intersection of design, technology and sound. “In the beginning I wanted to be a musician, but I eventually found out that I’m dyslexic,” he explains. “In 2002, I moved to Berlin to be a DJ. But that didn’t work out either. There was a totally different vibe there with minimal techno and tech-house.”

Decamping to London, however, proved to be a turning point for him. Suzuki found the perfect environment to experiment at the Royal College of Art. “It was a nice playground. I did a lot of interactive projects there,” he says. While figuring out how to connect the digital and analog worlds in new ways, he also learned to deftly navigate between artistic and commercial projects. Besides exhibiting at MoMA, Tate Modern, Barbican and Tokyo’s Museum of Modern Art, he has developed audio innovations in partnership with Google, Korg, Teenage Engineering and Moog. But as diverse as his endeavors may be, Suzuki is always searching for new ways to interpret and convey the sounds around us.

Yuri Suzuki’s first solo retrospective exhibition ‘Sound in Mind’ opened at the Design Museum, London in September 2019

“We have so many opportunities to design sound these days, because many objects are losing their physicality,” says Suzuki, referring to the tactile and direct interaction his installations offer as a contrast to the rapid digitization of many areas of modern life. “Also, as a creator, I do believe that combinations, in a defined sense, always give you a stronger experience. Such as the combination between the visual aspect plus sound can give a huge experience.” Expanding on the idea of social engagement that runs through both his artistic and design work, Suzuki adds, ”It connects to communication as well. Personally, I have a dyslexic problem and if I go to a museum, to be able to understand a work, if I have to read some caption or description of the work, that actually for me is really difficult. So something I have to do is properly experience without any description. To get to know the concept naturally – that's something I'm looking for.”

Music and music technology will likely always remain a key focus for Suzuki. And hardware has always played a central role in his approach toward music, which makes sense, considering his abiding interest in people’s interaction with sound. We spoke recently with Suzuki about two particular projects of his which transformed semi-legendary pieces of hardware into something new and united his interests in music, design and communication

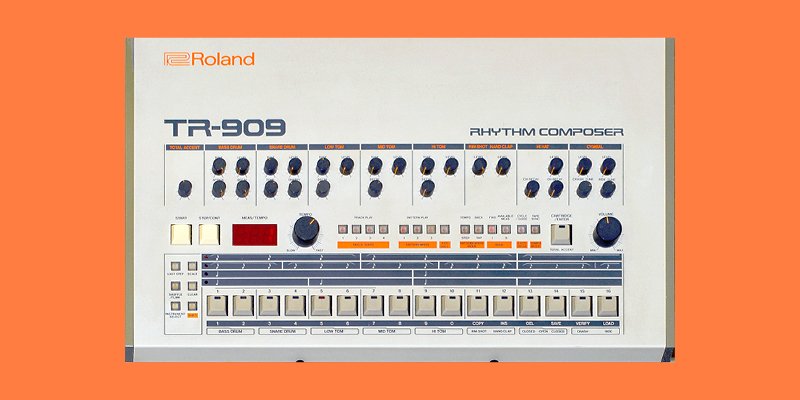

Suzuki collaborated with Jeff Mills to reimagine the design of his TR-909 drum machine

For “The Visitor” you worked with Detroit techno pioneer Jeff Mills to redesign his Roland TR-909 drum machine. What was the origin and the goal of this project?

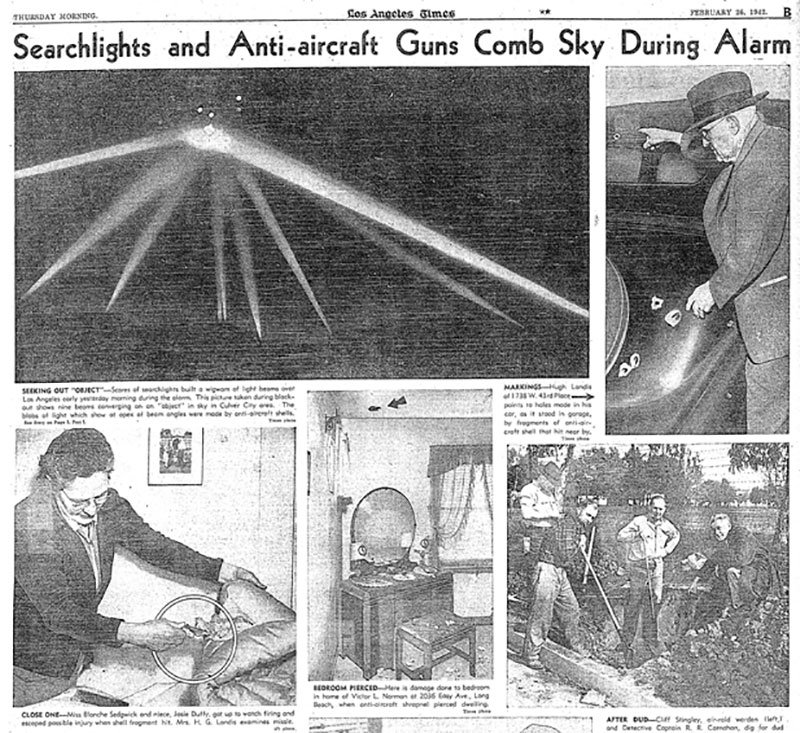

I think the project with Jeff Mills is a very unique starting point actually, because really it came from a discussion about narrative and a bit of a philosophical conversation. Because Jeff is really like a monk in a way. If you talk with him, he goes really deep, it's not on the surface, it's really philosophical in a way. So he was talking about sort of a sculpture project which he was planning to do at that time, and roughly based on the story he's really inspired by; an event called "The Battle of Los Angeles" which supposedly occurred during WWII. A kind of urban myth almost where the US Army was attacking something in the sky but there's nothing there. And some people think there was a UFO, that aliens were in the sky of Los Angeles – so that's kind of a really interesting myth of that time. Jeff is very interested in that kind of narrative or story. And also the photos from the time are absolutely beautiful.

Narrative and design inspiration for Jeff Mills and Yuri Suzuki came from archival photographs.

And so we just started there with the conversation, and how we can translate this story or narrative into a physical expression. In the beginning we came up with: what if that object could be presented as a shape, reflecting that picture and at the same time a functional instrument he can use for the stage. And so we came up with the idea of combining his existing TR-909 with an updated bespoke version for him. And so that’s how the brief came together from this kind of narrative and practicality. Then I started redesigning first of all the panel or the layout of the interface, because the TR-909 is really more about studio use and programming, it's not for live use. So first of all I started expanding, because you know Jeff has such fine, beautiful fingers and hands and he still feels it's not comfortable using the old parameters of the 909, it's too small. So we expanded it.

So the arrangement of the buttons and dials is different from the original?

Yeah exactly.

The layout of the original 909 was designed for studio use rather than live performance

But I imagine, Jeff Mills, after decades of being used to the original layout of the 909, his muscle memory would be pretty locked in.

Absolutely. He can probably play the 909 fluently without looking. But I think he wanted to have something that's more useful for him. So we made the controls and buttons bigger. Also we limited a couple of functions because some are not needed for live performance. And then a major change for the layout; actually the TR-909 is linear, isn't it? Just one line for the programming of 16 steps. But we tried to design for circulation rather than to go in one straight line because each time coming back here again [Yuri gestures to the start of the 16 step sequencer on the original 909] it is super disconnected. We want it to be continuous. And that's why the interface is a circular shape, so that's kind of how we changed it.

Function, aesthetics and practicality must all be considered in the making of new instrument

One tricky part was the selection of buttons and so on, because it has to be something beautiful but functional at the same time. So in the beginning I selected metal that looked like heavy duty buttons, but Jeff said this actually isn't useful for live performance because he's gonna hit them like crazy. So in the end we just used sort of arcade buttons but they look better than game center style. So color – we didn't select the cheesy red or yellow buttons – we found something like a subtle blue color and decided to use that. So it's really interesting that we had to consider that one side is based on a narrative he created but at the same time it had to work functionally as well, so there was this kind of long back and forth process with him to create it.

Yuri Suzuki explains his re-imagining of the Electronium – Raymond Scott’s instantaneous performance-composition machine

I imagine the Electronium project was rather different since Raymond Scott, the instrument's inventor and designer, never actually finished building it. The instrument was supposed to be an analog synthesizer and algorithmic composition machine, and Scott worked on it continually from the late 1950s until sometime in the 1970s. What was the goal with this project?

My intention with the Ramond Scott project was to try and make something real. Like, actually make what he tried to make. That was my ambition in the beginning. However the problem was the cost because I personally funded that project and for all of the circuit boards to be functional it was going to be an enormous amount of money, as well as time. So a quick solution was a simulation on the computer as a first step. But at the same time I didn't want to lose the physical aspect. So we made a touch panel screen to control exactly how he [Scott] wanted to do it. So this is kind of a practicality choice that led to an upgrade actually.

Who is the Electronium's owner currently?

Mark Mothersbaugh of DEVO. I went to his warehouse in Los Angeles and he showed me the whole structure and he showed me all the details. Also, sort of hidden documents from Raymond Scott, documentation about how he designed circuit boards and stuff. So I was kind of browsing all these elements. In the beginning it was really about looking at how things work, but we started slowly realizing that it was a bit simpler than we thought and some parts are not logically correct. So that was quite interesting to get to know inside of how Raymond Scott thinks. And that kind of came up a lot through reading and also in the artifacts, you know, how he left the documents. And mainly one document was quite helpful because the Electronium was commissioned by Motown Records [founded in Detroit in 1959].

Yes, that's an interesting Detroit parallel between the Jeff Mills project and the Electronium!

Absolutely! So, [Motown founder] Berry Gordy is a huge pioneer as well and he was really hoping for Raymond Scott to develop a kind of brand new technology to create music. I think Raymond Scott tried as best as he could but he just couldn't finish everything. At that time, in the 1970s, with the electronics and technology available he just couldn't finish it. He was quite a secretive person and he tried to do everything by himself. And if you look inside of the Electronium, it's just an absolute mess. It's incredible. I can see hand-soldered RAM, basically Read Only Memory that he tried to make by soldering. That’s absolutely crazy!

Then, he actually left one document, because Berry Gordy never kind of forced him or stressed him at all, he just generously funded millions and millions of dollars for that project. And in the end, Berry Gordy was asking him, can you show me how things work, so Raymond Scott left one document about how the Electronium works. So that was really the starting point, and also he had a big future vision about what he tried to do. So we basically analyzed the interface and talked with the relevant people who used to work for him, and then slowly discovered functions. So I didn't really add any functionality, but it's based on reading about and understanding the Electronium. So it's probably a bit different from the original but so far I've been able to make a conclusion for this project, I think.

And where is it now?

At the moment there's only one software simulation and we made an installation called 'More than Human' and it is showing at the Barbican in London. So that's how we're displaying it and that's now traveling around the world. But there's only one at the moment. But I really want to do an online or software version for anyone to play, that would be really helpful!

Words: Marc Young / Shure

Interview: APE / Ableton

Images: Yuri Suzuki

Also check out Yuri Suzuki's contribution to Shure24.com where he picks some of his favorite inspirational contemporaries from the world of sound, music and design. For more audio insights, check out LOUDER magazine from our friends at Shure.