A Brief History of The Studio As An Instrument: Part 3 - Echoes From The Future

In Part 1 and Part 2 of our History of The Studio As An Instrument, we looked back at some of the pioneers of composing with recorded sound and traced the earliest predecessors of sampling, looping and sequencing techniques. The story continues below with the emergence of dub, krautrock and disco; all musical styles which are closely linked to a few creative producers pushing the idea of the instrument further than what had previously been possible.

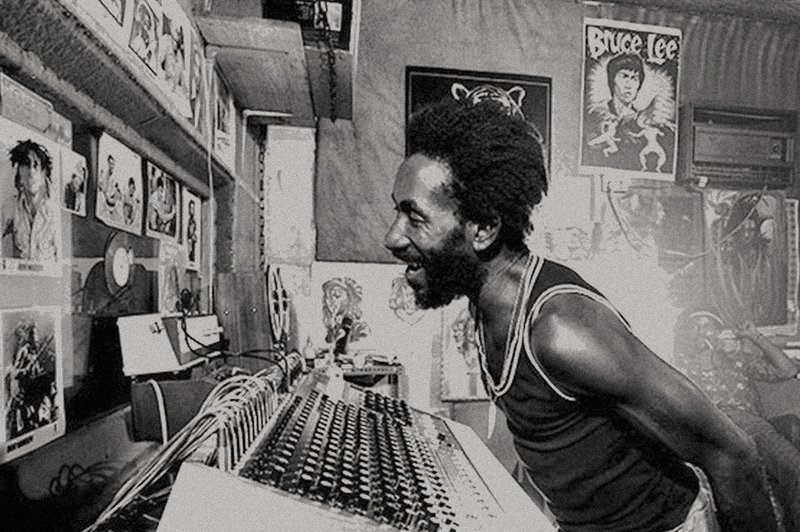

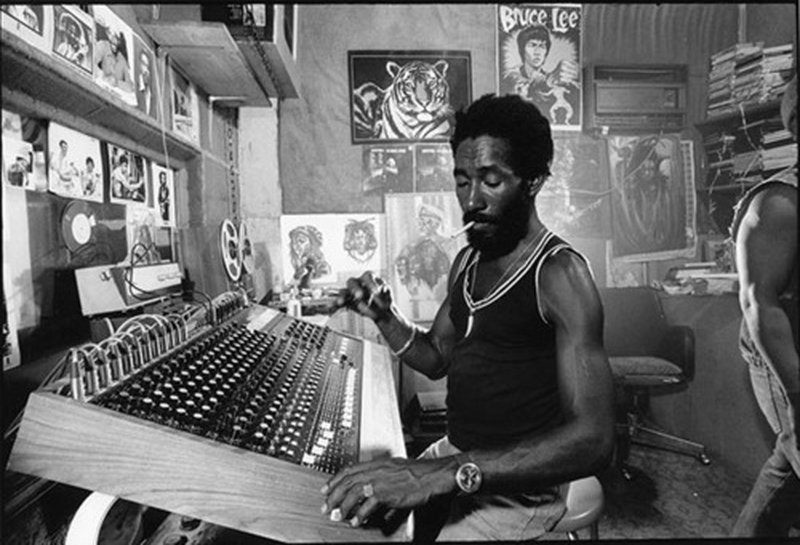

King Tubby and the Birth of Dub

In the late '60s and early '70s, dub – as a distinct style of music defined by a set of evolving sound manipulation techniques – would emerge to profoundly transform reggae music. Using (and abusing) delays, reverbs, filters and tape machines, dub practitioners would take previously recorded tracks, strip away everything but the drums, bass, some keys or horns, some fragments of vocals or melody and rework these skeletal structures into new, hypnotic shapes. In essence, dub marked the birth of remixing; taking existing material and creating entirely new compositions from it. As an approach (if not necessarily a sound), dub is a major part of the DNA of contemporary music production. From hip-hop to techno, grime to jungle and drum & bass, and (perhaps most obviously) dubstep, many latter day music genres can trace at least some of their roots back to the dub tradition.

At the forefront of the Jamaican dub movement was King Tubby. Born Osbourne Ruddock in 1941, Tubby's family would move from downtown Kingston to Waterhouse, an expansive area of western Kingston, in the early '50s, and settle into the house where Tubby would eventually set up his legendary studio. Showing a propensity for electronics in his teenage years, Tubby went on to receive formal training at the College of Arts, Science and Technology in uptown Kingston. Initially, Tubby used his training to find work fixing the transformers that stabilized electricity for businesses and homes around Jamaica, but he soon began using his knowledge for the benefit of local sound systems as well. Around 1958, Tubby established his own Hometown Hi-Fi sound system and became known for playing American rhythm & blues music. According to the demands of sound system culture, and in an attempt to one-up Hometown Hi-Fi's competitors, Tubby constantly devised ways to configure his system to sound better than the rest, and – as legend has it – his was the first sound system to introduce reverb.

As a natural progression from his sound system years, Tubby eventually made his way to the studio side of Jamaican music, though little is exactly known about his early days behind the boards. Eventually, Tubby got his hands on a two-track tape machine, which he began using to make exclusive "version" mixes for sound systems – revisions of previously recorded vocal songs, featuring alternate instrumental takes or emcees toasting on behalf of various DJs and sound systems.

In 1971, Tubby acquired a MCI mixing desk from Kingston studio Dynamic Sounds – Jamaica's most advanced studio at the time. The board greatly expanded Tubby's production capabilities when it was brought into the front room of his home at 18 Dromilly Avenue. With his newly expanded technical reach, Tubby was now able to route the individual parts of his versions through copious amounts of reverb and delay, and filter and mute elements with much more control and fluidity; this is how dub was born. A prime early example is his reworking of Jacob Miller’s “Baby I Love You So”; in Tubby’s hands, the rhythms of the delay, the addition of Augustus Pablo’s melodica and the delay applied sparingly but precisely, turn the nice-enough track into something a couple orders of magnitude heavier:

Soon, Tubby's studio began to attract the interest of local talents, some of whom would go on to be among dub's most important figures, including the likes of Augustus Pablo, Niney the Observer, Keith Hudson, Yabby You and part-collaborator/part-rival Lee "Scratch" Perry (more on him later). Setting up a vocal booth in a converted bathroom of his home, Tubby’s studio became the place for adding vocals to pre-recorded rhythm tracks, but more importantly, it made the studio the place where these artists came to have their dub versions mixed, often by Tubby himself. (It should be noted that Tubby was always assisted by a team of engineers including Pat Kelly, Philip Smart, Prince Jammy and Scientist). The trademarks of Tubby's style – swells of cavernous reverb, trails of clattering, feedbacking delays, extreme filtering, phasing and modulation – became the pillars of the dub genre.

Sadly, King Tubby's life came to a tragic end in 1989 when he was robbed and shot by an unidentified gunman. Though his time was cut far too short, Tubby was remarkably prolific during his life, leaving a legacy that not only changed reggae, but made a profound impact on the wave of production-based genres that would emerge in the '70s and '80s and continue to the present day. It's hard to overstate: dub’s emergence was truly a visionary moment, a foundational shift in the relationship between music and production whose traces remain discernable in just about every vein of modern music creation.

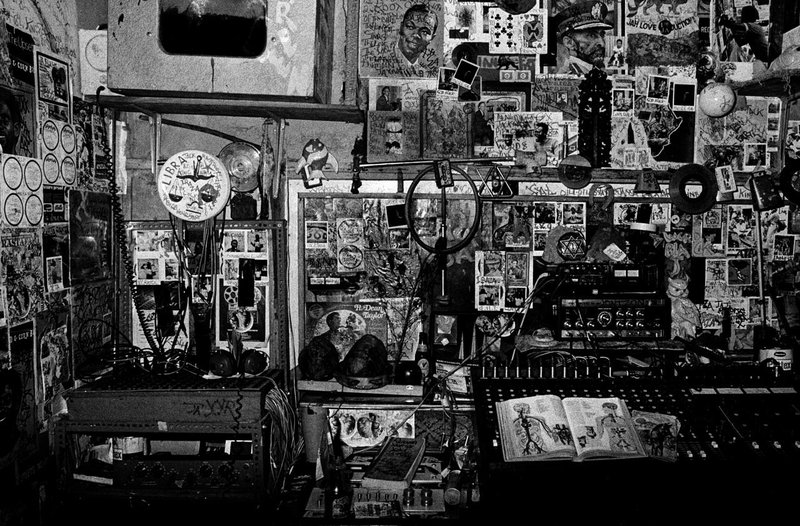

The Untamed Imagination of Lee "Scratch" Perry

Though King Tubby may be credited with more-or-less inventing dub, Lee "Scratch" Perry arguably stretched its limits the furthest, infusing it with elements of both humor and mysticism while crafting his own distinct style over 50+ years of studio work.

Perry was born in a rural Jamaican village in 1936 and, after coming to Kingston, began his musical journey in the 1950s, first working for ska artist Prince Buster and selling records for Clement "Coxsone" Dodd's Downbeat Sound System. Soon, Perry began producing and recording groups for Dodd's now legendary Studio One operation where he lent his talents to numerous hit songs. In 1968, Perry left Studio One to pursue his own independent label, Upsetter. The imprint's first single was "People Funny Boy," a record which not only sold extremely well but also marked the beginning of a new evolution in reggae, initiating the genre's shift from fast-paced ska beats to a slower, more loping, bass-focused backbeat that would become know as the "riddim."

In the early '70s Perry heard the astounding dub experiments King Tubby was working on and saw how his studio knowledge and production expertise could be used to similar effect. From there, a flood of dub mixes came from Perry and led him to open his own studio in 1973: Black Ark. A new artistic freedom took hold once Perry had a studio of his own, and although the equipment was far from state of the art, he had no trouble crafting fascinating and expressive tracks in the small space he had built in the front garden of his Kingston home.

The control room of Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry’s Black Ark studio

In Black Ark's early days, the main piece of equipment was a Teac 4-track tape recorder, alongside an Alice mixing desk, a Grampian spring reverb and an Echoplex tape delay – later a Roland Space Echo, and a Mutron phaser were added. Sparse perhaps, but those few pieces of gear, matched with Perry's ingenuity, resulted in dub and reggae masterworks such as Max Romeo & The Upsetters’ War Ina Babylon, The Congos’ Heart of the Congos, and his own Super Ape, Cloak And Dagger, and Blackboard Jungle Dub albums – among many others.

By the end of 1978 though, Perry had hit a breaking point, and so began the demise of Black Ark. At first, Perry became reclusive and reportedly began destroying his gear before the studio was mysteriously burned down. This, of course, was not the end of Perry's musical output. In the years that have followed, Perry has become a musical nomad of sorts, though he did at least settle down enough to eventually build another studio, Secret Laboratory, in Switzerland (which sadly also burned down late last year). In truth, Perry has remained an active producer for over five decades now, continuing to evolve his dub style, collaborate, and explore all sorts of new musical territory as his staggering back catalog continues to reach new generations of producers through an innumerable array of reissues and anthologies. Even if Perry had stopped after Black Ark burned down, it probably wouldn't have made that much of a difference; Perry, Tubby and all their dub compatriots had already transformed reggae and in the process, laid down the foundations for how producers would interact with audio for decades to come.

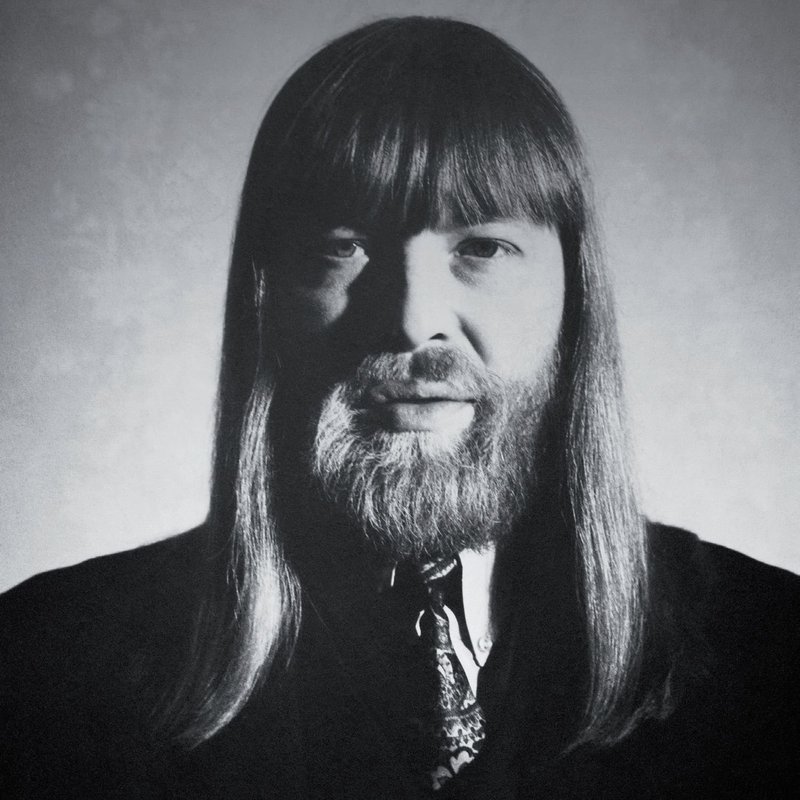

Conny Plank Redefines the Producer

With the advent of 24-track tape machines, the emergence of ever more sophisticated studio tools, and the proliferation of professional recording studios that began in the '70s and '80s, the modern era of music production was born. Massive mixing consoles now made it possible for even more instruments and sounds to be combined, isolated and overdubbed while new, more sophisticated delays, reverbs, and effects could be combined to make sounds and aural spaces seem as real or as artificial as the song called for. Essentially, this explosion of audio tools set the stage for the studio becoming a compositional tool in the making of almost any record.

Still, there are some who more fully embraced the new possibilities. One such visionary was Konrad "Conny" Plank, a German engineer and producer whose work with outfits like Kraftwerk, Can, Neu!, Kluster/Cluster, Ultravox, and many others blazed a new path in creative sonics. After a stint as an assistant engineer and producer around Cologne, Plank embarked on his own as a freelance producer in the late 1960s , initially working with legendary krautrock band Kluster and recording Kraftwerk’s self-titled debut album in 1970.

Though he was supremely gifted in technical terms, Plank saw his role of producer as not only a technical one, explaining once in an interview, "The job of the producer – beyond the technological aspect – is, as I understand it, to create an atmosphere that is completely free of fear and reservation, to find that utterly naïve moment of ‘innocence’ and to hit the button at just the right time to capture it. That’s it. Everything else can be learned and is mere craft.” Still, Plank's productions were notable for their depth of sound and the vibrant tonal colors he coaxed from instruments.

In 1974, Plank opened his own recording studio in a converted farmhouse outside of Cologne. Here, he produced groundbreaking records like Kraftwerk's breakthrough Autobahn LP and Ultravox's Vienna, encouraging both bands to embrace the synthetic sound world with a simple philosophy: “I like synthesizers when they sound like synthesizers and not like instruments," Plank is quoted. "Using a drum machine for electronic music is okay, but not if you try to make it sound like a real drummer." In the years that followed, a wealth of kosmische, krautrock, avant-garde, and other boundary-pushing records continued to come out of Plank's studio, including albums from Echo & The Bunnymen, The Eurythmics, Devo, and even Brian Eno (who later introduced Plank to U2 in hopes Plank would consider recording the band's next album, Joshua Tree; as the story goes, Plank reportedly said "I cannot work with that singer," after meeting the band.)

A musician in his own right, Plank fell ill while on tour in South America and passed away in 1987. In his wake , Plank left an incredibly wide-ranging catalog of music that essentially laid the groundwork for what the role of a producer would become in the coming decades.

Patrick Cowley Bridges the Electronic Barrier

Patrick Cowley was a San Francisco-based producer and musician whose period of musical output was short, but nonetheless profoundly impactful. In 1971, Cowley relocated to California from Buffalo, New York at the age of 21 and soon began tinkering with the limited electronic music gear he could get his hands on at the City College of San Francisco. Inspired by artists like Wendy Carlos and Giorgio Moroder, Cowley used the school's limited equipment to start an Electronic Music Lab to experiment with combining synthesized musical elements and real-world instrumentation to create hybrid compositions.

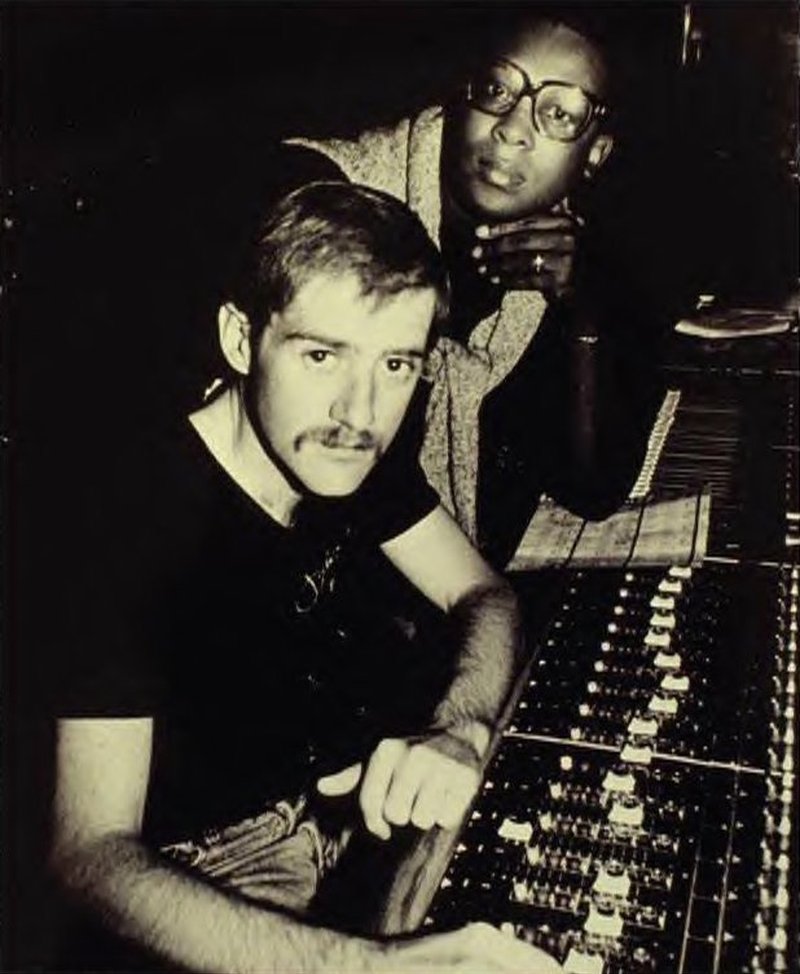

Patrick Cowley with Sylvester

Cowley quickly gained a reputation as a synth whiz and eventually gained the attention of San Francisco disco artist Sylvester. The two formed a close partnership, together pioneering San Francisco's Hi-NRG sound with songs like "You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)" and "Dance Disco Heat" which bristled with fast-paced rhythms and came flushed with space-age electronic tones. Cowley's talent was most potent in his ability to blur the lines between real and synthetic sounds, finding ways for them to seamlessly fit together. Along with his array of electronic machines, Cowley was said to keep a collection of percussive tape loops in his studio, sorted by specific drum sounds (kick, snare, shaker, etc.) and BPM so that they could be reused on different tracks, essentially anticipating the sample and loop libraries most music software includes these days.

An unapologetically out homosexual man in the heyday of San Francisco's gay culture, Cowley's music often revelled in the freedom he experienced within that community (song titles like "Menergy" were not meant to be subtle). As a solo artist, Cowley released a number of seminal singles on his own Megatone Records label (including Paul Parker's Hi-NRG hit "Right on Target") and issued a groundbreaking album of his own in 1981, Megatron Man. Tragically, not long after the record's release, Cowley became ill with what would later become known as AIDS – an early victim of the epidemic that would sweep through the US' gay population, a catastrophic event that for sometime overshadowed the community’s accomplishments in music and culture and left Cowley a somewhat underappreciated pioneer. That has changed in recent years however, with new material from Cowley's vaults (specifically, his soundtracks for artsy porn studio Fox) surfacing and showing a more experimental and adventurous side to the pioneering producer. With the aid of hindsight, it's much easier to see how far ahead of his time Cowley truly was.

Where We Find Ourselves Now

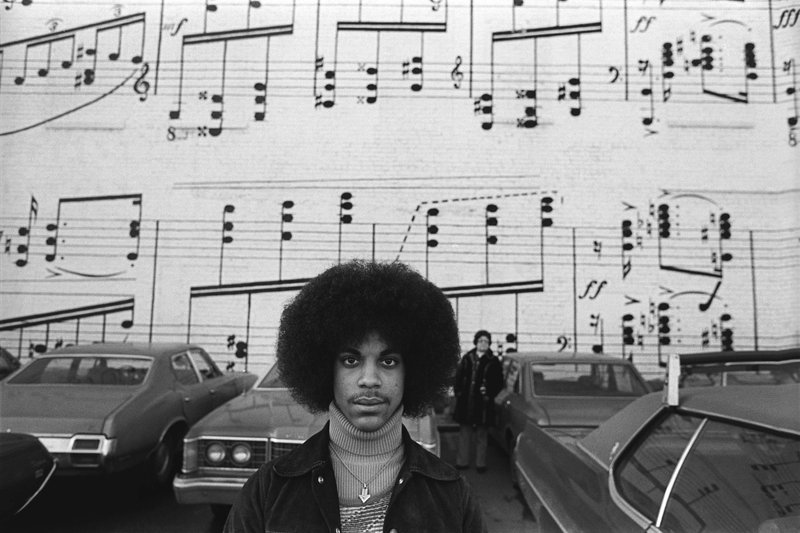

As we stressed in the introduction to this imperfect history, it would be impossible to truly cover every pioneer of the the pre-digital, pre-software era. Essentially, every hip-hop producer who has used a sampler, every techno artist who has gradually manipulated and automated a sound, and every studio tinkerer who has slapped reverb and delay in places others thought it shouldn't go, have taken part in and contributed to the evolution of the studio becoming an integral component of musical artistry. Artists like Prince – who, among many other accomplishments – engineered and played 27 different instruments on his debut album, For You and super-producers like Nile Rodgers and Brian Eno have contributed immeasurably to this lineage. The techniques, sounds and aesthetics first defined by hip-hop luminaries Afrika Bambaataa, The Bomb Squad, and J Dilla or techno trailblazers Juan Atkins, Derrick May, and Kevin Saunderson are more apparent in popular music today than at any time before – a testament to just how forward thinking their musical inventions were. We stand on the shoulders of these and many other giant innovators as we follow our own creative paths and express ourselves as artists, musicians and producers.

Today, the equivalent power of an entire studio from decades past fits inside a single laptop. While this convenience is remarkable, it is important to remember that these audio programs and platforms are just the latest step in an evolution which reaches back almost 100 years.