Sounds In Context: New Instruments from East Africa

Around a year ago we reported on a movement from East Africa that explored a new sense of excitement in the region, working at the intersection between traditional musical approaches and electronic music culture. A year on and things have continued to develop at pace. New festivals, parties and events have sprung up in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda focussing on a desire to represent and promote an ‘Afro-futuristic’ or ‘World Music 2.0’ attitude – and new styles, interesting collaborations and fresh approaches to live performances have flourished.

Collectives like Santuri East Africa have been at the forefront of this development, and have begun to further the conversation by looking at technology as a platform for traditional culture and heritage. One of the strands for this has been to encourage the development of an East African sample library, including new digital instruments based on and inspired by traditional instruments from the wide and varied cultures of the region. Four such instruments have been developed into unique Ableton Live Racks by Johannesburg's Emile Hoogenhout (a.k.a Behr) and can be downloaded for free.

Gregg Tendwa, a cultural activist from Kenya and co-founder of Santuri East Africa explains how this came about: “Many musicians and producers from East Africa depend on standard sample libraries that are available on their DAWs. The music produced can be good, but has none of the contextual authenticity that comes with adding a texture of heritage. With sounds collected from around East Africa, there’s much more scope for creating unique music that reflects the deep vibes of the region.”

Making an East African sound bank

Mirroring the global trend, the bulk of music production and recording in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda has moved beyond traditional studios. Most producers in the region do not have access to recording studios, quality recording equipment or even musicians to record. Santuri has been thinking about this issue for a while, and has been organizing ideas around developing an East African sound bank – a resource for producers, DJs and music makers to access sounds and instruments from their own backyard – and to share those sounds with producers around the world. And so to this end, Santuri convened a line-up of ‘roots’ musicians including Olith Ratego, Abakasimba Troupe, Msafiri Zawose, and Giovanni Kremer Kiyingi, to work together with Behr, who happens to be an Ableton Certified Trainer, in a workshop on building Instrument Racks in Live.

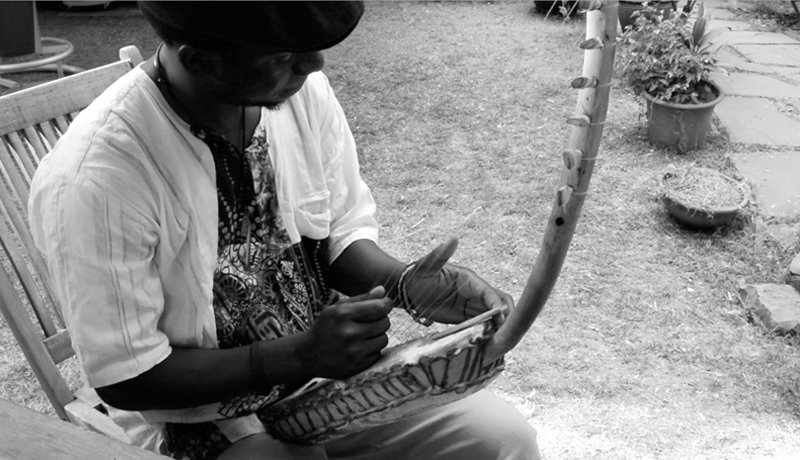

Behr’s deep interest in African instruments had led to him previously developing an mbira Rack, and over five days in Nairobi he had the opportunity to record four more distinct instruments found only in the East Africa region. Battling with less than ideal conditions, (sound insulation was in scarce supply and samples had to be recorded during lulls in other workshops), Emile set about capturing and translating instruments with unfamiliar and unique qualities into playable Racks – perhaps the first time these instruments have appeared outside of a traditional context.

“I wanted to approach this project with the utmost respect to the culture and history behind the instruments and musicians but with the ability to push the sonic boundaries with the use of Ableton Live. I sat down with all the artists and asked them about the history of all the instruments – everyone was very happy this vision of cross-pollinating the traditional with music technology."

Good quality recordings were essential to achieving this goal. “If the recording and processing methods were adhered to correctly,” notes Emile “the dynamic essence of the instrument would be embodied in a virtual context, with most of the organic nuances intact when playing different velocities on any MIDI device.” Working from this basis, he then added a few well-thought out macro controls to each Instrument Rack to control Arpeggiator parameters, Reverb, Filter Delay and sample reverse. With the ability to morph from the pure, multi-sampled recordings to heavily treated, filtered and arpeggiated forms of the same, Emile is making a concrete contribution of the Afro-futuristic aesthetic that’s to be bubbling up in East Africa.

Free Sounds from East Africa

Download the Pack from Emile’s site where you’ll also find a detailed description of the recording process. Read on to learn some of the social and cultural background the original instruments and musicians came from.

The Instruments

Zeze – Tanzania

The zeze can be found in various guises all over East Africa and beyond. Essentially it’s a stringed instrument that normally consists of between one and five strings running along a wooden neck to a open, resonating gourd. Previously, recalls leading exponent Msafiri Zawose, a zeze was called a “ching’wengng’we” – an onomatopoeia for the sound produced by the smaller versions.

The zeze sampled for this Rack is unique. It was developed and modified by the Zawose family of Bagamoyo – a coastal town one hour’s drive from Tanzania's capital, Dar es Salaam. The Zawose clan have been at the forefront of showcasing the music of the Wagogo tribe for decades. The towering presence of Dr. Hukwe Zawose led the music of the Wagogo to be heard worldwide through his tours and recordings with Peter Gabriel’s Real World Records in the 1980s. At home, he presided over a vast musical family of some 50 members, and pioneered a number of modifications and evolutions of traditional instruments to suit his development as an artist – from kalimbas of all sizes to the distinct zeze now played by his son and musical successor, Msafiri. The Zawose zeze is characterized by its size, having an unprecedented 14 steel strings. It’s made of dried calabash, wood, the skin of either a monitor lizard, goat, cow or python.

Msafiri, who recorded the zeze for this Rack, explains:

“I learned how to play the zeze when I was around 8-9 years old. By the time I was 16 years old, I had mastered the instrument and was able to make them on my own. I have a special love for the sound of the zeze, the way it can be drawn out and express a range of feelings and emotions. It can be relaxing and meditative, or it can be uplifting. Animals are drawn to the sound, and birds will often try to mimic its tones.

I learned to play the zeze from my father, who later developed zezes in different sizes and with more strings. The large zeze instruments did not exist in Gogo [one of the largest tribes in Tanzania] culture, especially the plucking style. It’s been exciting to develop songs on the large zeze because very few people in the world have a zeze like ours. Almost all are in the family, and even within the family, no one plays the zeze like I do.”

Adungu – Uganda

Two of the instruments developed into Ableton Racks hail from Uganda - the Endere (flute) and Adungu (bowed harp), and were both played by Giovanni Kremer Kiyingi – a young multi-instrumentalist from Kampala.

The Adungu is a nine-string arched (bow) harp of the Alur people of northwestern Uganda. There are strong similarities and possible direct links to the Egyptian Arched harp of the Old Kingdom – and similar instruments can be found in West and North Africa. Players of arched harps were often of a high social status. The informative Singing Wells website suggests: “Traditionally, the harpist was the only musician ever allowed to play in the room of the royal ladies, whilst there would often have been a harpist situated in the Kabaka’s palace (the chief of the Baganda tribe in Uganda). In some cases, a harpist was blinded by royal command either to make him immune against the charms of his audience or to keep him dependent upon his master.”

These days the Adungu is featured predominantly in wedding and funeral ceremonies, and can be heard either solo or in ensembles. Giovanni, the instrumentalist that worked on this Rack, began playing it at school, but was later taught by a musician who played in the king’s palace. He’s since become one its leading exponents.

Endere – Uganda

The Endere may be less impressive in appearance, but has just a firm a place in the Ugandan musical landscape. A flute of the Baganda people, the Endere known by several other names depending on the region – the Omukuri of the Banyankore and the Bakiga people, the Akalere of the Basoga Iteso people. The instrument is blown at the slightly V-shaped slit end of the instrument, usually with four finger holes. If the Endere is not used to accompany dancing, it is used to play melodies for the grazing cattle or to interpret love songs. Giovanni confirms this:

“I traveled to western Uganda with my father, where many children played the flute to the cattle while grazing and milking. All the time we spent there I was struggling to produce a sound from this flute. One day I got a chance to talk to the late Prof. Ssempeke – the best flute player in the kingdom. There began my love for the instrument. The Endere can produce so many melodies, which makes me love it more, and keeps me searching for new ways to play it.”

Ohangla Drums – Kenya

The drums recorded for this Pack come from the the Ohangla culture – born out of the Luo community of Western Kenya. Ohangla refers to a dance and style of music that was often performed at funerals, weddings as a part of Tero Buro – a Luo rite of passage. Ohangla had a reputation for very fast tempos and vulgar messages, and was associated with provocative dances and illicit home-brew, and as such Luo elders once decreed it was only fit for adult audiences. A famous Luo saying translates as ‘ohangla is never to be used for entertaining a woman’, such was its perceived seductive potency. It has now mostly lost this reputation, having found audiences across tribal barriers and become popular for celebrations of many kinds. Yet, Ochieng Moses Ochieng (a.k.a Moseh Drumist) who provided the recordings for the Rack here, testifies to its continued hypnotic power:

“These drums were used in sacred celebration ceremonies – their sounds are therapeutic and possess the audience. When I play these drums people usually go into a trance... It takes their souls on a journey.”

Africa Ni Leo (Africa is now)

The four instruments available here cover a wide geographical terrain, from the coastal areas of Tanzania to Western Kenya and Northern and Central Uganda. Scores of other equally unique instruments and cultures exist, many that have been all but forgotten during the rapid urbanization of culture in the region. Santuri’s interaction with these musical cultures provides a platform for rethinking their position within the creative landscape. As Behr elucidates: “music has constantly expanded and evolved with many applications through ritual and experience. This project echoes this sentiment that nothing is ever stagnant, which I feel resonated with all the artists, combining the traditional and the modern to the sonic world of the unknown.”

Gregg Tendwa of Santuri suggests that “as yet, we are nowhere near commenting strongly or authoritatively about an East African sound, and that is not the main reason for collecting these samples and developing these Racks. The idea is that the usage and validation of such sounds across a network of producers, DJs and musicians can allow an organic sound to emerge. When we hear a West African kora play, you know where that music comes from, irrespective of whether it's on a hip hop or a folk track. We look forward to a growing appreciation of these sounds globally, and an eventual recognition of particular sounds coming out of East Africa.”

Keep up with Emile Hoogenhout and Santuri Safari