Sidechain Compression: Part 1 – Concepts and History

From pop to hip-hop to sound design to heavy techno, sidechaining is an essential tool for modern production. Even if you don’t think you know it, you’ve heard it: it’s that pumping sound when the kick drum hits and everything else makes way. In this series, David Abravanel takes us on a journey through the history and applications of sidechaining, with some tips to boot.

First impressions of compression

Dynamics processing – especially compression – is so ubiquitous now that it’s almost novel to take a step back and look at where it came from. In the early days of recording, before DAWs and before even multitrack tape, recordings were done live, with the only kind of editing amounting to doing another take. And the ficklest instrument of all is the human voice. Consistency in vocal takes isn’t easy – performers need to maintain the right position in relation to a stationary microphone and be mindful of volume, both of which run counter to delivering an animated performance. Combine wide dynamic range (the gap between the loudest and softest sounds) with high noise floors of vinyl and tape media and you’d often have brilliant singers delivering unusable takes.

Enter the compressor. By making loud sounds softer, the compressor allows a producer to boost the level of a track, thus narrowing the dynamic range.

If you’re new to using compression or just want to review, here are some of the key terms:

•Threshold: the dividing level – sounds louder than this level are attenuated according to the ratio, while sounds softer than this level are left alone.

•Ratio: the intensity of the compression for signals above the threshold. For example, at a ratio of 2:1, a signal that is 2dB above the threshold will be attenuated by 1dB. At a ratio of 10:1, that same signal will be attenuated by 1.8dB. A limiter is simply a compressor with a ratio of infinity:1, such that the signal never rises above the threshold.

•Peak / RMS: this determines how the compressor perceives the loudness of the trigger signal. While RMS (root mean square) is a representation of the general loudness, peak responds immediately to current peaks. In Live 10’s meters, peak is shown in dark green while RMS is shown in bright green.

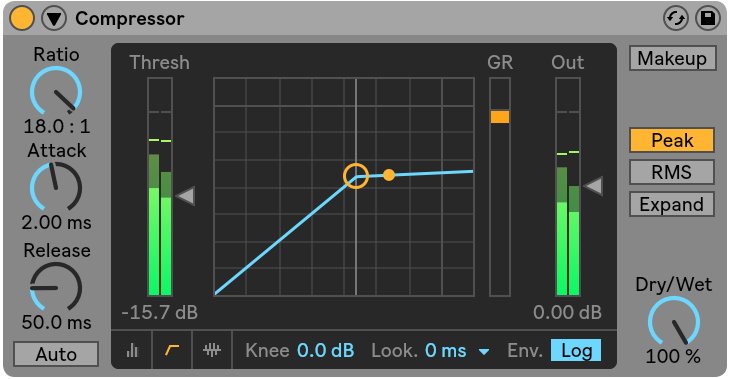

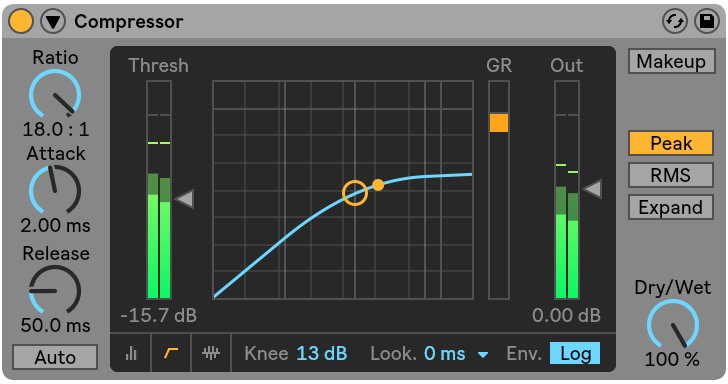

•Knee: determines the onset of the compression. A completely “hard” knee uses the threshold as a sharp “on/off” switch for compression, while a “soft” knee fades in the compression – such that signals below the threshold are gradually attenuated, while the full ratio isn’t reached until above the threshold. You can see the knee shape from which this parameter derives its name in the Live 10 Compressor by selecting transfer curve view.

A “hard” knee in Live 10’s Compressor.

A “soft” knee in Live 10’s Compressor.

So, compression was born and dynamics could be tamed for the first time. It should be noted that early compressors had their quirks – some of which are highly prized today, but which make them unsuitable for more precise applications. The Teletronix LA-2A, for example, does not feature a ratio control, while tube-based compressors such as the Fairchild 670 introduced nonlinear distortions. If you’re looking for this vintage flavor in your compression, Live 10 features the Glue Compressor, a component-level model of a legendary analog bus compressor from Solid State Logic.

Ssssssidechain

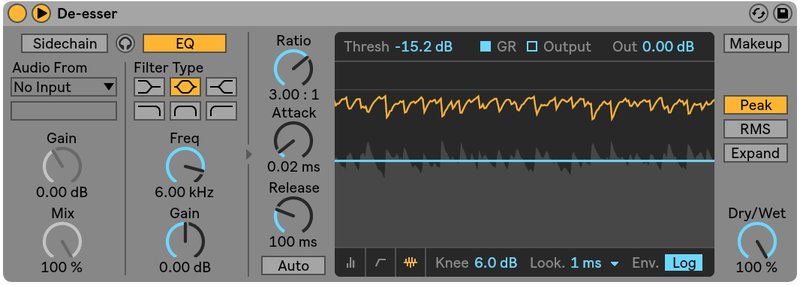

It may shock you to learn that the initial applications for sidechain compression in the 1930s were not directed at making French filter house. Rather, it started with a film audio engineer named Douglas Shearer, who needed a way to tame the sibilance (the hard “s” sounds) of dialogue recordings. Sidechaining was born when Shearer conceived of a compressor with a “side” signal chain (separate to the main trigger signal) with an EQ slapped on it – rather than evenly compressing the incoming signal, this “de-esser” would only be triggered when the specific sibilant sounds appeared.

The “De-esser” preset in Live 10’s Compressor – notice the EQ portion of the sidechain section.

While traditional compression has a signal affected by its own trigger (i.e. the louder it gets, the more compression is applied), sidechaining uses an external (or processed) signal as a trigger for the compression.

In the decades that followed the invention of sidechaining, it was used primarily as an effect for voiceover – when a song drops in volume while a radio DJ speaks, or the muzak quiets down for someone at a grocery store to make an announcement, that’s sidechaining in action. In fact, that’s a specific effect of sidechaining, known as “ducking”: this is when one audio signal is reduced proportional to the level of another audio signal.

Cr-SMACK-ash

The musical history of sidechaining would be incomplete without sidestepping briefly to overcompression. Sidechaining isn’t the only way to accomplish ducking effects – compress a signal heavily enough, and you’ll hear certain elements dominate the narrow dynamics to the extent that other instruments sound muted. In 1966, The Beatles freaked their share of minds with the psychedelic “Tomorrow Never Knows” – but while John’s spiritual lyrics and Paul’s wild tape loops received the most acclaim, it was Ringo’s drumming, compressed to a pancake by engineer Geoff Emerick, that looked to the future of percussion. Listen to the white noise-esque din of the cymbals, broken up by the smack of the kick and snare:

This overcompressed sound became a hallmark of rock and roll and funk, and birthed the concept of using compression not just as a utility, but as an effect.

Finally, French Touch

If you’re familiar with sidechaining, you’ve probably been waiting patiently for this article to address the pumping sound of French Touch. Built on samples of vintage funk and pop songs run through filters and phasers, sidechaining served a practical purpose in turning sampled music into something new. If you’ve got a sample that you want to place prominently in the mix, but you also want the kick from your drum machine to be clearly audible, sidechaining is the way to go – here’s Daft Punk working this process with a sample from Karen Young’s “Hot Shot”:

Daft Punk and their peers – such as Motorbass and Cassius – created a fun monster with this style, resulting in pumping pop hits like Eric Prydz’ “Call On Me”. When it comes to French Touch, the kick is king. With such extreme settings (low thresholds and high ratios), you could pile on the synths and samples without worrying about the kick getting lost in a mushy mix.

It bears mention here that, despite all the legends about expensive gear, in the case of Daft Punk, their first two classic albums Homework and Discovery relied on the consumer-priced Alesis 3630 compressor for pump. It’s all about what you do with what you have, really!

Fat Beats

The 90s saw pioneers of sampling pushing new gear to greater lengths for fatter tracks. While early hip hop revolved around live bands playing funk instrumentals, and the mid-80s favored jazzy loop diggers like Stetsasonic’s Prince Paul or harsh minimalists like Rick Rubin, the 90s made way for greater diversity, including claustrophobically banging beats. When it comes to influence, there’s no one more important to the legacy of pumping hip hop than J Dilla.

In his tragically short lifetime, J Dilla mastered the art of soulful beats that gurgle and pop through the speakers. While sidechaining might not have been a favored trick in his technical arsenal, overcompression was present, and resulted in samples ducking kicks of a butter level that no one else seems to quite match (though Dilla’s friend and collaborator Madlib comes close).

In the 00s, Dilla’s influence could be felt directly on a new pack of beatmakers thinking outside the box.

In the FlyLo track above, everything ducks the kick – even the vocals, resulting in short-cut words. Sidechaining wasn’t just an effect, it was a creative choice to subvert expectations and make a track respire. Even the kick itself seems to be swallowed, which suggests that perhaps FlyLo put a sidechain on the master – an unorthodox but highly effective move.

Weirder, harder

Once an effect takes hold, it’s only a matter of time until someone abuses it to create a new level of effect (see: auto-tune & Cher). When it comes to sidechaining it didn’t take long – try not to hyperventilate to the organs in this Autechre track from 2001:

Similarly, artists like Amon Tobin, Andy Stott, and Emptyset found ways to build breathing tracks around sidechain compression. Going even further, UK producer Actress asked what happens when you heavily sidechain a track with a kick and then remove the kick itself from the final product:

Not to be left out, producers like Surgeon, Audion, and Paula Temple put the hard “ch” in Techno by sidechaining whooshing noise effects with massive industrial kicks and percussion.

Pop goes the sidechain

With the ‘10s ushering in the age of cross-pollination among pop genres, it was inevitable that sidechaining would grow out from EDM and hip hop into the mainstream. Whether it’s Araabmuzik taking on Deadmau5 and Kaskade, Clams Casino & Soulja Boy, or the bleeding edge of lo-fi rap with JPEGMAFIA, sidechaining is as common to the language of music in 2018 as the human voice itself.

Why is sidechaining so popular? The easy answer is “loudness and computing power”. If you think back to the dawn of digital recording, instruments still had to be played one at a time. Additionally, early computers that could generate audio couldn’t sustain too many tracks or effects – so stacking 10 lush synths in a row just wasn’t a possibility. Today, you can create a maximal sound that would make the THX theme blush from any laptop…and then have it all duck a fat kick, of course.

Like other pieces of the musical vocabulary, sidechaining facilitates expression – whether that’s pressure, claustrophobia, the vibe of a club soundsystem, or playing with psychoacoustic expectations. In part two of this feature, we’ll look at some standard ways to sidechain, and some truly experimental ideas.

Want to stay up to date with us?

For more news, blog posts and videos, sign up for the Ableton Newsletter.