Ropes, Fields and Waves: Celia Hollander Sculpts Time with Sound

Ascending the tall, narrow stairs of Celia Hollander’s apartment in Los Angeles’ Highland Park neighborhood feels like entering a cloud where the fragrance of citrus blossoms mingle with the morning’s coffee brew. Her compact, modular studio accentuates a desire for functional flexibility, a setting that bends to sound’s calling. Scattered across several sunlight speckled walls are framed illustrations drawn by the same hand. These architectural renderings and advertising treatments are like portals to idyllic realms, possible futures frozen in two dimensions. When Celia first stumbled across them, she recognized the signature slope of her own pen on the pages and was mystified since she had no memory of sketching them. Celia soon discovered they were drawn by her grandfather, a man she had never met but whose hand was somehow coupled to her own across generations. It was as if the fabric of time had parted, connecting Celia through memory and dream to a greater continuum.

“6:33 AM” - the lead-off track from Celia Hollander’s Timekeeper

Celia has always been fascinated by how the marking of time makes us feel and she filters this into her music. Einstein of course determined that time is relative and its passing depends on the speed of your own motion. So in 2020, when the whole world halted and stuttered, temporal perception became especially blurry. And from where Celia Hollander stood in Los Angeles, she acutely felt the effect. As a composer with a background in architecture, Celia already thinks a lot about time and space but it was during the suspended state of the COVID-19 pandemic that she began to intentionally frame temporal categories in her compositional practice in order to make sense of what she was experiencing, an audible viewfinder of sorts and tool to bend the clock.

Hollander’s album Timekeeper was born out of these exercises. Released in the summer of 2021 on Leaving Records, the album is made up of 12 tracks, each categorized as a Rope, Wave or Field—three distinct perspectives on time (more on that later). If you were to miss its heady concept though, the collection would still be a delight. Celia conjures a sort of ambient-adjacent audio liquidity where lush, polyrhythmic streams fade in and out of earshot but feel as if they have been flowing in space all along. The music provides a sense of motion that’s comforting in a time of disorientation, as if the sounds themselves are gently nudging us along with an encouraging wink. And like her late grandfather’s illustrations, Celia is sketching imaginative frames that aren’t bound by the constraints of a pre-built reality but rather lay their own foundations for the infinite potential of the moment.

Celia and I sat down in her studio to talk about her relationship with time and how she’s been examining it through her musical practice.

Celia Hollander (and Tempo) in her Los Angeles studio

Was there an early experience or acknowledgment of time that fascinated you?

I studied architecture as an undergrad, and I was always fascinated with the factor of time in architecture. I was really interested in the idea of a building as having a life – it's conceived and then it's constructed, and then it's used. It changes over time, especially based on how it's used. And that's what all of my research and creative projects focused on: how a physical structure can be shaped over time, through physical forces, natural forces, natural disasters, but also just based on how a person wants to use it. It’s an evolution that happens over time. So it's not a static object. And after a while, it was just like, I'm interested in time more than architecture. Architecture is this vessel for time. And I've always been interested in music, and music is ultimately a medium of time. All musicians, composers, performers and producers are engaging with that.

Do you find yourself drawn to a sense of calm time when you're making music recreationally, like a slowing of the metronome in order to wind yourself down?

Definitely. I think one of the best parts about being a computer musician is that you can really marinate in your own music. A lot of the music that I make is what I want to listen to. When I'm working on the computer, sometimes I'll spend time crafting a palette of timbres and make a bunch of loops and then I'll leave it on for hours, and go in the next room and read and hear it through the wall and I'll just leave it on to get acquainted and deeply familiar with it. And then maybe the next morning I'll add the next part. So it takes a lot of time, it doesn't happen in real-time, and listening is the main part of the process and that can be done really directly, like just sitting and listening, but more often it's oblique or with other activities.

When I'm very calm and grounded, that's when I'll write more high BPM textural polyrhythmic, overstimulating music. Maybe a bunch of high frequencies, a ton of clicks and small samples and it could be really driving or like a storm of panning and lots going on, buzzing. And then other times, maybe if I am furious, the music that will come out will be the exact opposite. It will be extremely grounding and long form. Also, as a listener of other people's music, when I grew up in L.A. I wanted to listen to extremely dark, aggressive music. And then I went to college on the East Coast, where the culture shock was brutal. It was so cold and bleak, and I could only listen to synth pop or warm, happy music. I couldn't take the music that I craved in the sunshine in Los Angeles. And I think that it's definitely not a coincidence. It's an added layer to your environment. I seek this balancing between all these variables, including my internal emotional state, and the external weather.

“I think one of the best parts about being a computer musician is that you can really marinate in your own music.”

It's interesting to think about the tempo of music created as the inverse of your internal state. When you're anxious or stressed and you want to slow down are there ways that you, as a musician, intentionally slow down or quicken time? Is tempo always connected to it, or are there other ways to get there?

There's so many ways. And this is so complicated because BPM might seem like an obvious choice, but there are genres that are really fast in terms of BPM, but they feel very slow. Sometimes footwork feels that way, because they throw in these triplet wrenches, and it has this retrograde strobing pattern effect where it feels like it's like tripping backwards.

Like an audible illusion.

Exactly. It's at a breakneck speed, but it's not four-on-the-floor. It's really complicated, and there are things interfering with each other. And sometimes it almost feels downright slow in this weird way. So this is to say that the experience of what feels fast, slow, forwards or backwards, up or down or accelerating, decelerating is a complex combination of what makes music music: BPM, frequency, harmony, melody, texture, dissonance, consonance. I haven't found the formula, and I think I've set out on this noble quest to tinker with that.

I've been really interested in sparseness recently. Some of the earlier music that I made was more harmonically dense, like a wall of sound continuously. DRAFT for example, I'm playing piano, and then it's a lot of processing and layering that piano. In every track, there is no silence. It just goes. It's like a waterfall, zooming in on the small bubbles, froth. It's just continuous. I've been really interested in injecting space, not necessarily silence, but dynamics and having air pockets. Sometimes that can have a lightening effect and sometimes it can have a slowing effect. I think predictability has a lot to do with whether something feels like it has inertia or it feels like time has stopped and you don't know what's going to happen next.

Let's say I have a bunch of loops and all of them are different durations and they have sparse events in each one of them with a bunch of space. Playing them back, depending on the level of density in each of those loops, because it's random and the durations of sparseness are random, you can hit an air pocket and just have no idea when the next sound is going to come. And it can sound really long even though it's only a few seconds. Whereas if you put space in something with a regular periodic cycle or BPM, it seems to have more of a lightness effect, which doesn't make time feel like it's going slower, it just makes time easier. Less heavy, but not necessarily slower.

Is this all gauged primarily against your internal clock or are you thinking of where others might sit with it?

Yeah, this is 100% subjective. This is my own personal project. And I think that's also a really interesting factor to throw into the mix, the way you receive music is so subjective and different for everybody. And even for me, like in the course of a day, the way that I experience a song can change. For example, one time I was making a song that was definitely beat-based and working on it at night and I'm like, this is perfect, everything is just right. And then the next day I listened to it in the morning, well rested, caffeinated, driving in my car and was like, this is way too fast, this is out of control. And that's just me, that's the same person but the effects of environment and your mental state and substances like caffeine, for example, can change it. So it has to be a personal exploration, because there's so many variations in my own perception and at the end of the day, this is art not science. I do share it and I'm always interested in how other people perceive it because who knows?

I was at an art residency at this center in southeast Utah and I set out to make twelve audio-visual pieces, like music videos but more emphasis on the music and less on the video. Each one would be five minutes and have a drastically different type of temporal experience. One of them was a pop song and was footage of driving on a desert road really fast, and another one was much more ambient and droney and it was just a video of a billboard in town that was deteriorating and the wind flapping the crust of this billboard. I had a screening at the end and that was one of the only times I explicitly was wondering how it landed. Like, is this working in the most fundamental sense of what I set out to do? It was really interesting, I could feel it, the five minute piece that was just a drone was really boring. And you can sense that collectively, and the pop song was more engaging, and you can sense that collectively too. In a way I feel like that project spurred a lot of thought that I have had since then.

One of a series of “five minute temporal exercises” Hollander produced at Epicenter in Green River, Utah

Tell us a bit about your album Timekeeper and its exploration of space and time.

Timekeeper was the result of the first year of the pandemic when my physical landmarks disintegrated because I wasn't leaving my house and I was just left with time itself as the changes that were happening during the day. Like that anecdote I described about a song that seemed perfect at night and then way too fast in the morning for some reason. I interrogated that idea. There was a cluster of songs I was working on that were melody based, another cluster that were harmonic based or waves of chords and other ones that were just like ASMR texture explorations, randomness. And I started to organize them in these first, second and third perspectives of experiencing time. And then emboldened by that definition, I used that to solidify and further define these three different time experiences into music. The best that I could.

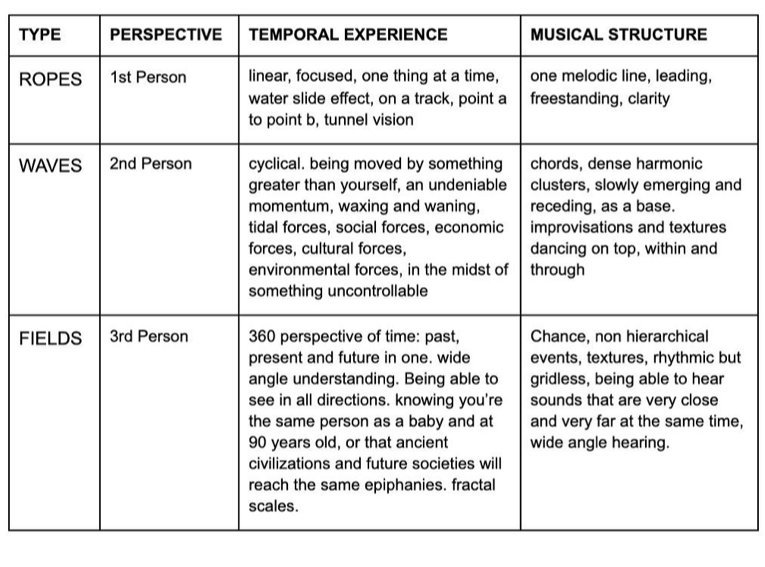

You made a chart of those three categories. Was that drafted to explain the concept to your audience or was it something to help codify and guide your composition?

It was definitely a personal thing and then I decided to post it on Instagram - people were like: “What is this?” I was like: “It makes sense, right?” The first category I refer to as Ropes, a first person experience of time, linear time that has a start and a finish. It's like getting on a bike path - you know that if you keep going, you're going to get to point B. It has a tunnel vision effect. It's very conscious, can be goal oriented, it's singular. Musically, that type of composition strategy is melody based. And I call them Ropes because I think of them as being one line from beginning to end. They might have knots or curves, but it's very much like one water slide.

“1:17 PM” – an example of what Celia Hollander calls a Rope track

So “1:17,” for example, is just one note at a time throughout the whole thing. There's nothing else. There's a lot of panning and timbre modulations, but it's just one melody. The second category, Waves are a second person experience of time, time happening to you, being pushed around. This is neither good nor bad, or it could be either or both. It's larger factors that are affecting your sense of time. That could be a pandemic, that could be being at a party, that could be any of these things that we've talked about that affect your sense of time in some way. And I call them Waves because a wave is just a transference of energy and you could either surf it or fight it or go under it. And so musically, these Waves are dense harmonic clusters. “5:59 PM” is a Wave Song and it just consists of these deep swells. There's a melodic part that dances on top and I consider that as riding these Waves.

And then the last category is Fields, the third person perspective, like a 360° view of time. Spatially, that means being able to see all around you in all directions. And temporally, I think of that as being able to perceive the past and the future as one. This is a very cosmic stance. It's yourself as a baby and yourself as an elderly person, as the same entity connected in this way. If Ropes are linear time, Fields are cyclical. Also, if Ropes are consciousness-based, Fields would be subconscious. It's a very wide-angle view, fractal scales. I call it Fields because I'm thinking of sonically standing in a field and hearing all around you, but more importantly, being able to hear things that are really close and really far away at the same time. So you might hear a plane going by, extremely far away and out of your reach while hearing crickets right next to you and also something rustling in a tree very far away. So it's about approaching that 360° scale and dimension and on Timekeeper those songs are the more textural, random, ASMR-y ones.

“11:01 PM” – a Fields composition

And did you immediately know, jumping into the creation of the album, this one's going to be a Field song and this one a Rope or a Wave or did that reveal itself through the process? And could the Field contain a Rope that's off in the distance?

Yeah, you're really reading my mind. During the pandemic I played a live stream show and it was one of the Fields in Timekeeper with me soloing on top. I then take the MIDI from that, finesse it a bit, expand it, isolate it – that becomes a Rope. And the Field that was just the foundation for that Rope gets fleshed out and spread out and that becomes a Field. But yeah, it was more of a feedback process because it wasn't like I wrote out that chart and then tried to make music for it. I was working on these things and started to identify or categorize them, mostly just for organization. I was like, what is happening? What day is it? What did Trump say today? What do I do with all of these insane files in Ableton on my computer? So, yeah, it's just a way to get through my own material. But when I had this distillation of modes, I could bring it back and use that as a tool to crystallize and organize these three bodies of experiences. Also, I want to be clear that within a Rope, a Field or a Wave, there are so many different ways to feel or experience that and there's an infinite spectrum of what that feels or sounds like too. But compositionally they have these main components and characteristics.

Are there tools and techniques that are complementary to shaping each of those specific categories?

The Ropes were primarily made through improvising on a MIDI keyboard, isolating a melody, a linear perpetual motion piano. The Waves were made in a really stupidly, laborious computer process which I can explain if you want... I'm dreading trying to explain it.

Think of it from the perspective of a Field and step back... The album's already made.

Well, I was trying very earnestly to create sets of chords that could feel like they resolved but neither felt like you could label them as major or minor or easily identify them. And have them sit in a vague, gauzy way but without hiding anything either. Like without obscuring or without using effects. Just through pitch and tone and timbre create these dense harmonic clusters of not necessarily confusion but suggestion, more like a question chord than a statement. And I couldn't make them with my own hands because I have all of this muscle memory and I have all these ideas about where my hands should go for jazz chords and what that should sound like. It's tiresome for me. I can't escape it with my own hands.

There's probably a pretty elegant way to do this if I was a programmer. I am not. So what I would do is, let's say I am working with a flute sample, which I was. I made about eight tracks of that same sample. For each one, I detuned it either randomly between negative 14 and plus 14 cents. So not too far off. But none of them are at the same tune. They're not all at 0 cents - it's a pretty big range. 14 cents is when it starts to sound wobbly or noticeably off. And then on each track, I played two notes at a time on the keyboard over the course of five minutes. And then I would do the next track, like a parlor game without listening to the one before, but doing it at the same time visually because I can see the MIDI blocks. And doing that, I don't know, eight times. And then you have all these randomly generated chords. Like I said, there's definitely a better, quicker programmer way to get there. This is the analog way that I did it.

And then I listened back to them and some of them sound really normal, some of them sound totally dissonant and some of them are just breathtaking to me and are something that I couldn't make with my own hands, no matter how many fingers I had. And so then I isolated all of those and rearranged them and tried to arrange them into threes for that song specifically. I'm like, if this song is going to be all about chords and harmonic clusters, I really want to explore what I can make out of that. So, yeah, that's definitely more of a computer and human collaboration. And then Fields, all of them are made by making a bunch of loops at different durations and letting them cycle. So that's like a Brian Eno strategy.

Less laborious, but equally fulfilling?

Yeah, in some ways that can be more laborious, too. It depends how far you want to go with it, and how many combinations you want. And sometimes for me, that's more of a process of making as much as I can and then carving away. I wasn't trying to make “jungles,” I was trying to make more of a “field at dusk.” That was more of a subtractive practice because it's actually easy to just make a ton of sounds and layer them in random loops and then it can take a lot of time to figure out when the ikebana of frequency and timing feels correct for whatever maniacal task I've given myself.

Do you feel at ease with time and your relationship with it as a musician?

How do I feel about my time spent on this earth, fiddling with MIDI bricks indefinitely? I think I have a lot of anxiety about time, and one thing I'm prone to do, if I have anxiety about something or if I'm afraid of something, is to try to understand it. And so I think that has spurred a really fascinating practice and set of exercises and a type of beauty. But I do think I'd be lying to say there wasn't also an undercurrent of sheer confusion. Why do we experience it this way? To face time is to face mortality. It's this resource that's not renewable. I think my goal is to have a comfortable relationship with that.

Follow Celia Hollander on her website, Instagram and Bandcamp

Text and interview: Mark McNeill

Photography: Alex Tyson