Although not a household name, Craig Leon’s career as a producer is about as distinguished and varied as it gets. An important figure in the original US punk and new wave scenes, he was responsible for the discovery and early development of The Ramones, Blondie, Talking Heads and others. Production credits also include Suicide’s 1977 debut LP, Richard Hell and the Voidoids’ Blank Generation, as well as records by The Pogues, The Bangles and The Go-Betweens.

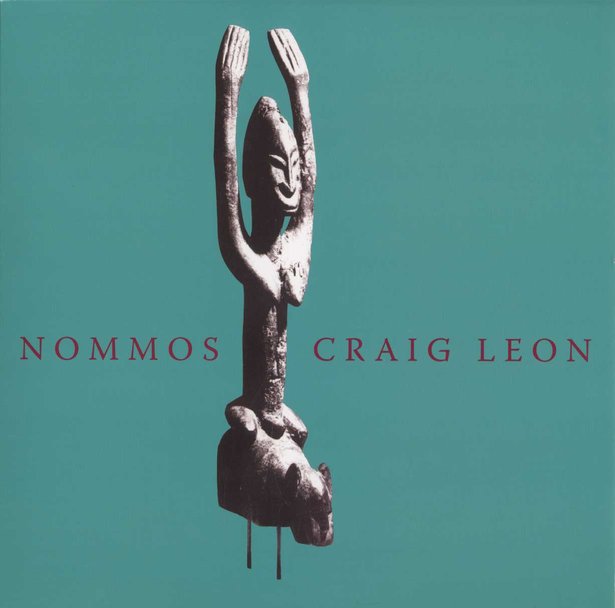

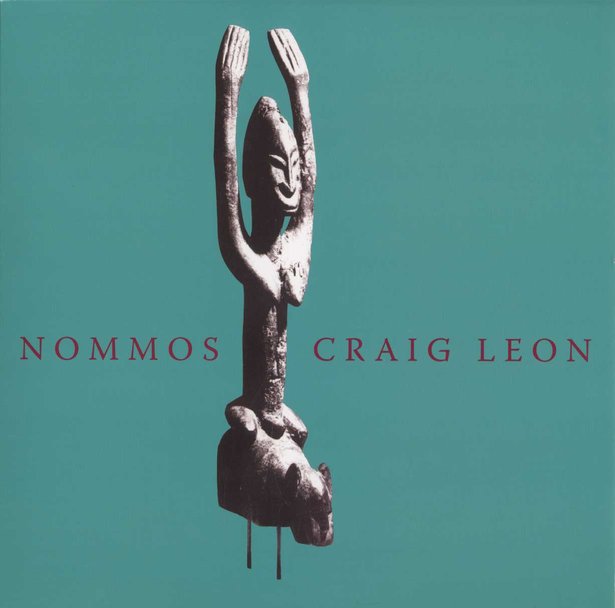

As a recording artist in his own write, Leon also forged a distinctive path. His 1981 solo debut Nommos was barely noticed when it came out, but this collection of jagged electronic percussion and watery, immersive electronics was years ahead of its time, and was acknowledged as a proto-techno masterpiece when it was re-released in 2014.

The last 25 years have seen Leon active mainly in the world of classical music (he originally trained as a concert pianist) working as an arranger, producer and highly sought-after recording engineer. His latest project however, joins the dots between two seemingly far-flung points of his career and of musical history; 17th century baroque music and the analog synthesizer technology of the 1960s. We sat down with Leon after his Berlin performance of Nommos to discuss playing his electronic works live, Dogon mythology, and what Johnny Ramone and J.S. Bach have in common.

What did you use to produce Nommos originally and what were the challenges of reproducing it on stage some 30-odd years later?

When I was first asked to go and do this old piece [Nommos], I was looking for a system that could actually help me get around some of the technical issues involved and be able to play it live without having to bring ten modular synths around with me. Nommos was originally done mostly on modular synths or very simple polyphonic synths, and the sounds were pretty much hand made. There were no sequencers involved, no digital technology. There was a very primitive version of the Linn Drum as the actual rhythmic source. And when I say primitive, I mean it was a prototype that wasn't even labeled. It was something that Roger Linn was starting to make. He loaned it and I put it on the record.

With the Linn, I played that live to multi-track tape when I did it. I didn't know what it was supposed to do actually. There was no manual, nothing was labeled, but I realized if you set a pattern every four bars, it might loop, which is kind of what I was writing intentionally. I wanted these four bar African oriented loops to play, so I would just do one and I would just keep playing it, and play over it and change it all the time, and that created the actual bed of what the percussion track was, that I then processed.

For the performance, I had to take loops that I'd made up from these original processed drum loops, and that's what I'm playing over when we play live. I wanted something that would actually put them in time, because I didn't quantize anything. I played them in by hand and it was very very loose, and that's what's on the record. That's actually the charm of a live performance and I wanted to keep that but I wanted to be able to do it in an organized way every time that we played it live. So the warping in Live enabled me to take these very slight differences and notate where they were, and then give myself visual cues in Ableton so that while I'm conducting I know “...right now I'm at 112.3 BPM”, and then have a whole bunch of tracks going in Live, but they're mostly visual cues to conduct.

I warp my click track that I'm using visually from the actual original analog loops. So basically the click is going up and down, the click is not constant…let's say in a given section you'd be going between 111 and 113 BPM over a 30 bar period or a 60 bar period or something like that. It's quite subtle, but to me those drum patterns, keeping them in that kind of arrhythmic pattern or variable rhythmic pattern, is part of what makes the whole thing flow up and down and makes it more of a listening experience than a groove experience.

Nommos doesn’t sound like any other music that was happening on at the time. What was the initial inspiration for the pieces on that album?

The pieces were inspired by an African tribe, the Dogon. A lot more people are aware of them now but they weren't so much in 1973 when we first saw the Dogon art and decided to make the record. They Dogon have these beings that came down from another planet in another solar system, and taught them everything they know about life and how to be civilized. You know, how to fish and hunt, and build houses and stuff like that. But that's being very, very simplistic about it. They actually had a huge philosophical and religious system, that's pretty much when you look at it, it's like "Oh my gosh, that's actually the roots of Egyptian civilization!" You know, it's very close and kind of makes sense geographically. [The Dogon live in Mali, West Africa] And so their whole culture is basically everything you ever wanted to know about these guys from another planet, and they called them Nommos. And to the Dogon they were these tall, elongated creatures who could live in water or on land, and who came from a specific far away star system which they just happened to describe as Sirius. In fact, they accurately described it as a binary star system years and years before anybody knew what Sirius looked like.

Craig Leon’s 1981 album takes its name and inspiration from the mythology of Mali’s Dogon people

For the past couple of decades you’ve been working largely in the classical realm. Has the recent interest in your electronic compositions had any repercussions in that part of your work?

I'm a firm believer in incorporating synths in an orchestral environment and with the classical labels that I work with, Nommos has now allowed to do more of my own projects. When I was at Moogfest, I was fooling around with a couple of things with a fellow named Malcolm Cecil who's one of the founding fathers of Moog and Tonto's Expanding Head Band, as well as a great jazz bass player. And we were just kicking around some ideas about running orchestral instruments through Moog modulars, which you can do. So in any case we were talking to Moog and it turned out this was the 50th year of the Moog modular and it was the 10th anniversary of the death of Bob Moog and we said "Well let's come up with an album for it." So I spoke to Sony classical about it and they said "Well can you do something with Bach?" because [Wendy Carlos’] Switched on Bach is the album that got everybody, myself included, into synthesizers and understanding that there was this instrument that you could do something different with. And that’s how Bach to Moog came about.

Craig Leon with the Moog System 55 Modular synthesizer

Bach to Moog is not the first album to apply electronic instrumentation to Bach’s music. What is it about his compositions that lends itself to interpretation with electronics?

Bach is like the ultimate sequential artist. Monophonic loops that intertwine and basically create a huge remix … that’s what a fugue is. I didn't want to make Switched on Bach, Part Two – I mean you just can’t, it's a classic album. I've heard people try and play Switched on Bach live and stuff, twenty guys playing a Moog or something, it just doesn't make sense. What Wendy Carlos did with that was groundbreaking and cannot be duplicated at all. So I said well I'll try and do something my way with Bach, which would be very similar to what I did with Nommos: take Bach, rearrange it in a new way orchestrally, and then process the orchestral instruments through the Moog audio-in. At the same time playing monophonic lines on the Moog in certain places as part of the arrangement, to the point where the Moogs actually blend in with the orchestra. The idea is to create dialogues between a solo instrument – in this case a violin that's slightly processed – and the Moog as a classical instrument. And it's all being done together, not done where it obviously sounds like a Moog or it obviously sounds like an orchestra but kind of blurs the lines between them.

"Bach is like the ultimate sequential artist. Monophonic loops that intertwine and basically create a huge remix … that’s what a fugue is."

How did you achieve the blend of orchestral and synthesized sounds?

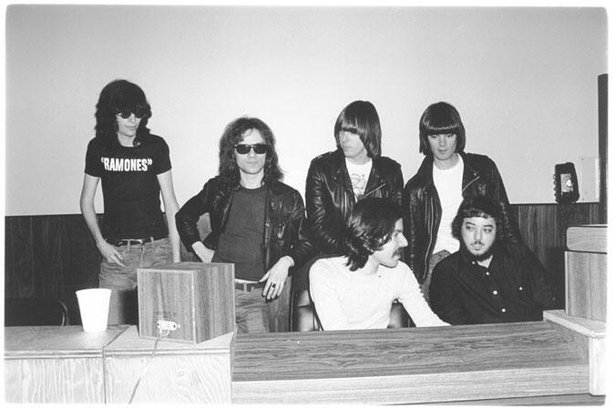

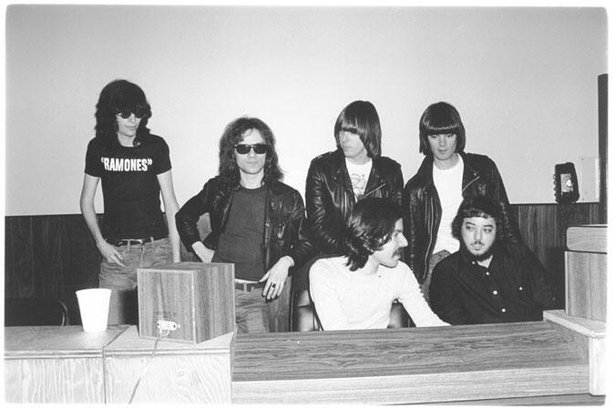

The really cool things about the old Moog models, like the Model 55, which Wendy Carlos used impeccably, is that there's this fixed frequency filter system, with these fixed frequencies. I was able use that to keep the intonation so that the strings and flute sounds and everything would all meld together, and it would actually be more of an orchestral blend. So what I did was these composite sounds off of a violin mic that would be one very extreme frequency boost, and then another track with a different one, and then another combination and you'd do eight or ten tracks and then you'd layer them down to one. And strangely enough that's what I did on the very first Ramones album to get that guitar sound. It's like loads and loads of different mid-range, very sharp EQ, all mashed into one compressed sound. So it's really hysterical, putting Bach through the Moog – it’s the same kind of technique as Johnny Ramone's guitar.

Craig Leon in the studio with The Ramones in 1976

I'm very much into the mathematics of music, and that's why I like Bach so much. Because he's really into that. And so what I would do on any reverb that I use is pick out very, very specific frequencies that I can create feedback from by feeding the output back into itself and then either using it an octave higher or lower or whatever to create an effect. And I do that even in classical.

I always like the interaction of different genres and different things, and nobody should be stuck in any one. The thing is that music is music and yeah, there's a definition, but whether it comes through your unconscious or it comes through something that you studied combined with your unconscious or whatever, there's no one genre or way of way making music that's any better than another. I mean a guy playing a blues lick, you're gonna be hard pressed to say "Is Blind Willie Johnson any better than Bach?" I doubt it, or "Is Bach any better than him?" No. You know it's just people making music in the way that they know how.

You certainly seem to be applying the same or similar organizational principles across the various genres.

Well, that's because I was trained as a keyboard player in from very early on. And so that's why I do it, but that doesn't mean you have to know that. I think what's really great about modern digital culture is everything is open to everybody now. I mean there's part of it that’s sad because nobody makes the royalties that they use to make, but everything is available, and that counteracts that quite a bit. You could take Aphex Twin and orchestrate it, if somebody was so inclined. I'm not volunteering to do it, but if somebody wanted to that, they could take that and turn it into something in sonata form, and put him in a style similar to Schubert or something. Why not? And you could go the other way around – so if anybody wants to remix Bach they can do it.

Download the individual stems from Craig Leon's recording of J.S. Bach’s "Jesus bleibt meine Freude” from the album Bach to Moog.

These stems are for promotional use only, not for resale or commercial use

Keep up with Craig Leon on Facebook