Body Meat: Blending Worlds

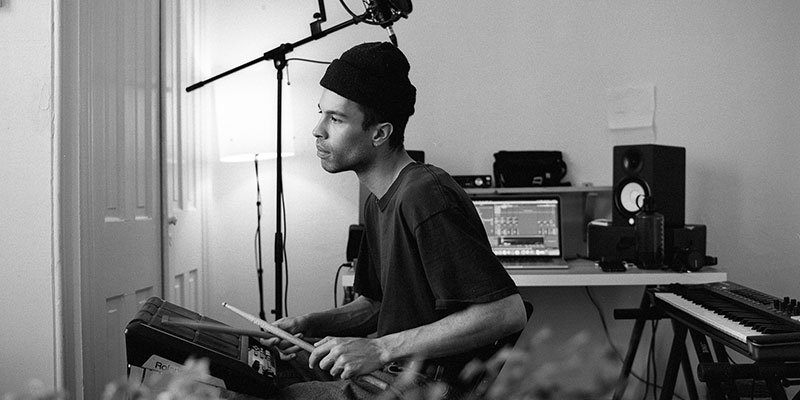

Christopher Taylor in studio. Photo by Beth Town

When Philadelphia-based electronic musician Body Meat (Christopher Taylor) dropped his seventh album Truck Music last year, listeners could hear the deft and acrobatic fusion of genres like trap, glitch, Chicago footwork and R&B. Truck Music is a sliced and chopped genre patchwork, executed using unexpected technique and singular logic that results in songs that sound like multiple tracks at once.

While Taylor delights in ripping tracks apart at their seams, there is an undeniable beauty in that brokenness. His creations are prismatic and in flux, but the experimental sound design of Body Meat always has pop music as its inspiration and endpoint.

Taylor’s sonic experiments are by no means the product of endless editing and stitching. Quite the contrary – Body Meat’s sound is firmly grounded in live performance, augmented by sampling drum pads, a MIDI keyboard, and guitar for various sounds, as well as his own vocals, sometimes chopped and glitched, other times shining through in the upper register.

Some of Taylor’s earliest memories are of his mother singing in a falsetto on the back porch of their “yellow house”. At the time, he was 7 or 8 years old, so he can no longer recall the songs she sang, but the moment stuck with him. Taylor also grew up listening to a lot of music by the genre-hopping 70s band Earth Wind & Fire, while car rides with his father would invariably feature a combination of late 1990s pop music mixed with artists like Luther Vandross and Sade.

“What I was trying to do sonically on Truck Music was to use sounds of my biology and ancestry and where I come from with the music, creating a palette that I could learn from,” says Taylor, who emphasizes that he never has a plan or concept before writing and recording. And, on Truck Music, the listener can sense that Body Meat is no mere exercise in the musical now, but a project that can accomodate the many sounds of his youth. Although Taylor’s music reveals a fascination with multi-faceted sound, he is clearly not interested in polishing recordings to perfection.

A few weeks back, we spoke to Taylor about his musical education, and how he first got into making music. We also discussed the evolution of his recording process from using digital recording decks to music software, but without completely ditching his tried and true songwriting techniques.

You grew up in a small town, right? How did that impact your later musical mindset?

Yeah, I grew up in Pennsylvania in a really small area called Avon Grove. I moved around quite a bit, and when I was 12 my mom left my father and moved to an apartment in Delaware. From there, I moved to Elkton, Maryland, which is where I grew up and went to high school – the formative years where you figure out what you want to be.

When I was young, pretty much the only music I was listening to was the music my parents had on, or it was the Pokemon soundtrack. [Laughs] I listened to that soundtrack so much. I had so much anime when I was a kid. I still love anime, it’s my favorite medium, but when I was younger I listened to the Pokemon soundtrack and the Dragon Ball Z stuff. My brother got me dubbed Dragon Ball Z tapes when I was 10. They had curse words on them and I was trippin’. We went to South Philly to an old manga/anime shop, and that’s where we got a bunch of Dragon Ball Z and Trigun dub tapes.

Was it in Elkton, Maryland where you originally got into guitar?

That’s where I knew of people that were making music, and that’s where I met my best friend, Andrew, who got me into the aspect of sitting down and listening to music. He got me into these emo CDs like Silverstein and Hawthorn Heights, but I was also super into ACDC. I was into old emo music like My Chemical Romance, which is still an amazing band, by the way. They’re super positive. If you see footage of Gerard Way now, he’s the cutest old dude. I get really good vibes from them and I’m not ashamed of it. So, Andrew got me into the idea of trying to understand music.

As I went through high school, I also got into serious hip hop. For a little while I was super into Immortal Technique, and then I was into Jedi Mind Tricks; a lot of the stuff that had to do with skateboarding as well, like Gang Starr, particularly the album Moment of Truth. I listened to a lot of Wu-Tang Clan and Big L, which is super problematic these days since Big L says a lot of awful shit and it’s outdated, but he has really good music.

Wu-Tang Clan’s beats hit hard – the ‘90s was a great period for hip hop.

I agree. I even listen to late ‘90s to early 2000s hip hop production and it’s crazy. I do believe it’s all cyclical and it all comes back. That style of rap is always going to be coming back and changing.

I listened to a Brandy song the other day. I liked Brandy but I never tried to dissect her music and production, but this song was almost like a footwork song. People were just snapping. There was shit like that going on during that era of hip hop and R&B that was really cool. Even big pop songs, the more I hear the stuff the more I take notes. The way they have the hi-hats and certain small to giant 808 beats – the transitions were big and fast, almost like breakbeat. I love that stuff and I still take notes from it.

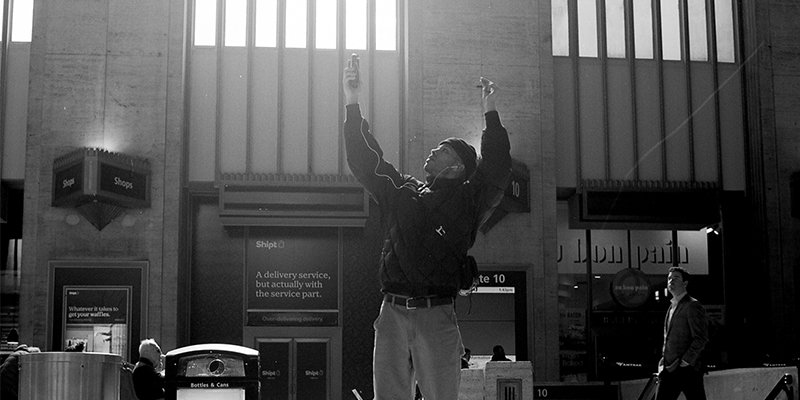

Recording 30th Street Station. Photo by Beth Town

There’s some really tight production by hip hop producers in tracks by female R&B singers. Especially the stuff produced by Timbaland and The Neptunes – for example, the stuff Timbaland did for Aaliyah, like “Try Again”. The production on that track was amazing.

Yeah, he snapped! He’d have 30 kicks in a chorus, and it’s like no one can ever humanly feel that but I like that a lot. It was kind of unruly, and I think that’s why I like music now so much. Even with the trap stuff, a type of music is super weird at first and there are no fuckin’ rules, and then it evens out where people figure out how to make that thing and they do the same thing for two or three years, and then something new happens to it and there are no rules again. I always love that in-between period where there are no rules.

I love that idea where you can repeat something like 30 times in a row, and it’s the only thing in the song, and it can be #1 in the country. I’ve seen it done at a DIY show, but you can trick the most low-key normal people to listen to the weirdest music.

It’s kind of like the movie Inception, where you’re planting ideas in the heads of the unwitting.

That is exactly what it is! And that’s what I draw on. I love current pop music and how these kids are making stuff, but I try to dissect what is the inception point for drawing normal people in and then they’re along for the ride. How loose can I go with this idea of pop music, and how far can I push it until people start jumping off? It’s a weird conversation I want to have with people.

Going back to your early formative musical experiences, at what point do you pick up an instrument and start making music?

I got my first guitar right before college. It was a really cheap acoustic from a pawn shop in Elkton. My friend taught me how to play a Bright Eyes song and it was the only thing I could play. I learned to play guitar from that song, but I was really just trying to learn chords to write my own music. I recently learned “Never Too Much” by Luther Vandross just so I can get better at playing those chords on the piano.

I moved to California to go to art school and that just didn’t last, so I started doing photography, but I still messed around with the guitar every so often. Then I moved to Oakland, and my friend Andrew and I would record into our friend Stephen’s interface with one mic. We wrote a few folk songs but I was really just trying to get better at playing guitar. I moved into a tent in this backyard at my friend’s house in Oakland because I was transitioning in life. I had no idea where I wanted to go and no idea what I wanted to do. I was pretty broke and still shooting photos and hanging the film inside the tent. I would also write music into Garageband on my laptop, but I didn’t know how to use it really. I didn’t release anything but I had a bunch of songs.

I ended up moving to Denver and I got this small 8-track, a Boss BR-600 digital recorder, and started writing music into that. I would program the drums with the electronic drums on the 8-track, and that’s how Andrew and I recorded a few songs on it. I actually wrote the first Body Meat tape all on that recorder. The 8-track has a mic on it that I would use to record guitar and percussion from pots and pans.

From there, my friend Evan in Denver gave me a bigger 12-track digital recorder, which had a big screen on it, a memory card, and multiple mic inputs. If he’d never given that 12-track I probably would have had someone else record my stuff. My music sounded like a Stevie Wonder song to me, like it was done at a professional studio. [Laughs] I bought a really cheap drum set and started recording percussion through one mic into the recorder, and entire songs were based entirely on drums. It would have to be one take of drums and I’d play guitar over it, which I’d run through a vocal pedal that could change the tone of the guitar into a synth. Later, I found out about a MIDI pickup that obviously changed my whole world.

I could record full songs on that recorder, and I think that’s why I started Body Meat. I could make music any time I wanted to and in any kind of style. I just wanted this thing that was mine, where when I was fed up with things I could just be Body Meat and create whatever I wanted.

Later, I took tracks from the 12-track, bounce them as .wav files to Ableton Live 9 Suite, where I would mix and master. I never recorded on Ableton Live because I didn’t know how to do that yet, and I didn’t have an audio interface at that time either.

Were you slicing and chopping audio in the digital recorder?

I was slicing in, but the only thing I could ever really slice in well was drums, which was why I always wanted to do drums in one take. For guitars and toy keyboards, I would try to cut them into the 12-track recordings I had. I would pitch them up and down, and I’d try to use my voice as a rhythmic instrument. It all kind of turned into what I do now, just without a computer. I tried to sample but I didn’t have a sampler, so I had to do everything live. There are parts where I’m doing backing vocals and I’m trying to make it stutter like a sample. [Laughs]

Even though they were made on a digital recorder and not done in a DAW, do early recordings sound like what you do now?

Definitely. Two weeks ago, when this whole quarantine thing started, I went through my creative catalog; which, by the way, is a great time to do this and puts a lot of things in perspective. When you listen to old stuff you can kind of put yourself where you were in that moment. Thinking about now, the world is so different and will be so different. In listening to old music – and this is interesting – early songs sound way closer to what I’m doing now than what is on the releases just before Truck Music. On those releases, I wrote the music and brought people in to play the parts. But on Truck Music, it’s just me like with the earlier music I recorded.

Now, I realize that I’m not just one thing. I think that’s why the early recordings sound the way they do, which some might say is scatterbrained. My interests are not just one thing, and as I get older I find that I’m embracing that more. I’m willing to see all of these things that I’m good at, that I appreciate, that I spent time on, and embrace them. I’m trying to embrace my blackness more, I’m trying to embrace the guitar more, and bring all of these different things into the music instead of picking one thing. That’s what the music industry will do to you: it makes you want to pick a thing, but you don’t have to.

How do you currently put together a song?

It’s kind of similar but it’s just electronic now. I use Ableton Live and my computer as the 12-track, and I record everything off of an electronic drum pad, the Roland SPD-SX. I’m triggering all of the drum samples and hits on that drum pad, and then I’m playing melodies on a MIDI keyboard with instrument racks with sounds of horns or people’s voices. Before quarantine, I was recording sounds out in the world. I stack all of this stuff together to create my own instruments in Live. I’m able to create entire movements on a pad and it sounds like a fully-produced track.

You mentioned that you spend a lot of time creating a sliced-up effect but by playing live on the electronic drum pad. How much editing and arranging do you do once you’ve recorded a track?

It’s very limited. The only type of editing I’ll do is if I’ve recorded a drum beat I’m happy with, I might delete certain hi hats and other hits, especially if a beat shouldn’t overlap with vocals. I don’t really like warping anything and I don’t play anything onto the grid. Sometimes I will quantize things but it’s literally only for a second to make a beat make sense. So, I don’t really move things around, I just finesse the song a bit so I can learn how to play it live.

Recently you’ve begun to sing in a falsetto. Can you talk about that transition in your vocal performances?

Like I said, my mom was a piano player and singer, and my dad played congas, so my whole life they were playing music. My mom would sing in a falsetto, and I always chose to sing to a song in a falsetto because it felt more comfortable. In early Body Meat songs, vocals weren’t a key part of the music so I kind of stopped singing – it was just little things here and there that sounded like samples.

Recently, I wanted to make this music but have really good vocals in it. I wanted to bring it back but sing in a falsetto, though I was never really super good at singing in a falsetto. My friend Matt said I should try using auto-tune, so I thought maybe I could mess with it. I used a few free random auto-tune plugins and they weren’t very good, but from that I realized I really liked using it. I could sing these crazy falsetto runs with auto-tune. I bought this crazy TC Helicon Voice Live pedal from my friend Evan, and I started recording my auto-tuned vocals with it.

It’s funny, and I’m not trying to flex at all, but auto-tune won’t do the thing that people like to hear. I kind of had to relearn how to sing with auto-tune on – it’s like a new instrument. For the new stuff I’m writing, I’m still using auto-tune, but I’m learning my natural voice more. I can sing on my shit. I don’t need auto-tune, and I’m not using it as a crutch. I’m using it to create a note I couldn’t possibly hit. I’m just trying to create this world where it’s a little jarring for people.

I’m trying to create something from one sounding thing to a drastically different thing. I’m trying to make music where a song is like several different sounds. I heard this song by Playboy Carti and Lil Yachty, it’s called “Balmain Jeans”, and it literally sounds like there are three different songs in it. And I thought, if they can do this, I’m going to try to make it work. It’s a crazy song but it’s beautiful.

What were you trying to do musically and thematically on Truck Music?

I was searching radio stations for sounds and samples in countries in Africa my father had visited, and where I may have distant relatives living in. It was an experiment in searching for understanding through sounds.

Musically, I wanted to combine all of what I had learned thus far in creating. I wanted to make something beautiful, but equally jarring. I was trying to push standard R&B music qualities such as the vocal style and sound palette, but also push the popular music standard of rhythm and time. Truck Music came out of trying to blend multiple cultures and worlds – worlds which I inhabit as a mixed race person everyday. So, with this new music I’m only trying to understand that more because I don’t think I fully grasped it with Truck Music. But, I think I’m getting close.

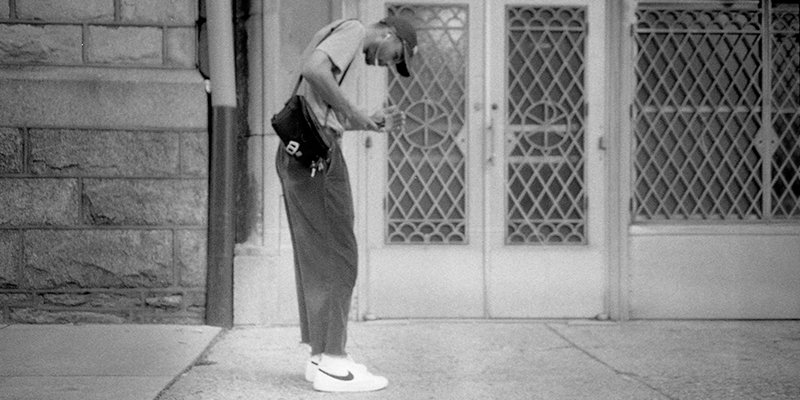

Recording church bells. Photo by Beth Town

You mentioned cataloguing your creativity during this pandemic. How have you been dealing with the acts of making music and being creative during the quarantine?

I wanted to post something on the Internet about how I wish I could be one of those creatives who has the privilege of creating through this but I just don’t have that mental privilege in my mind because of having to survive or just making it for so long. I can’t just turn it off, especially now that it’s really terrifying and you don’t know what’s going to happen.

I’m looking out the window right now and I’m right across the street from a health rehabilitation center and I’m seeing ambulances pull up every five seconds. I’m seeing people in masks walking around the streets. Do I matter right now? Does my music even matter in the world right now? What we need right now is help for healthcare workers, and we need to make sure everyone we love is okay and people stay inside. That’s where this sentiment came from where I wish I could be one of those creatives who can use this quarantine time to just make stuff.

I think if you do have to sit there and figure out your plan, try to talk yourself off the ledge of this panic attack and try to view the world as how it is and accept your situation, then what you’re going to create is going to be better. You’re going to be in the moment, you’re going to be present, you’re going to be thinking of these things while you create. You’re not going to be using creation as escape, which is what I think a lot of people do and which is what I used to do a lot. What I’ve learned is not using your creative time as escape but using it as a tool so that you can figure out your situation, and put the situation into the music. Whatever feeling you have in that situation, don’t let it escape even if it makes you feel uncomfortable.

If you don’t feel like you have the mental energy to make music during a pandemic, it’s going to be okay. It doesn’t mean you’re not going to make music again, it just means that, yo, it’s just music and this should be fun. And if you’re not having fun right now, then you’re not going to have fun making music. You need to get your mental state correct and be able to accept the world and your situation and take it day to day because that’s what helps. Then you’ll be able to sit down at your computer and say, “This is part of my day during a pandemic. This is what I’m going to write because it makes me feel good.” You’re just creating a new world for yourself.

Right, and then the music will come organically. Maybe even more organically than before this crisis.

It’s true, it’s so true. I hate that people use times of struggle and desperation as a thing. I do believe that great things are created out of times of stress and desperation, but I do not think only good things are created. I think that if people have mental ease, financial backing, and no struggle, they would create equally interesting things. But, I do believe that right now if you are mentally able to understand the situation that you’re in, and you’re able to pull yourself up and create through this, I think you can make something beautiful.

Speaking of creating music, you put together a sample pack. Can you talk about your approach to it, as well as how you envision musicians and producers using these samples?

This is my first time making a sample pack. I went into it with the same energy I have when looking for good samples – trying to create a palette that can be fully used for an entire song.

I recorded most of them with my field recorder. It’s a mix of sounds I've found walking around Philly, banging on things I thought sounded nice and just listening to my environment. Also, I created a few instrument racks for melody one-shots. That’s with a mix of my own sounds and things I recorded from talk shows on radio stations streaming in other countries. I like samples that have multiple sounds or melodies on them. I really like to work from one sample in multiple different ways, so I tried to implement some of that.

I guess I hope to see how far people can push the samples, taking my one-shots and loops and turning them into something unrecognizable because that’s really how I use samples. Also, nothing is warped or to a grid in any way which is how I normally work, so I’m interested to see if people do find them fun to use at all. [Laughs]

Keep up with Body Meat on Bandcamp and Twitter

Interview conducted by DJ Pangburn – a multimedia journalist, electronic musician, and video artist based in New York City. He DJs, records and plays live under the name Holoscene.