Spatial Awareness: A Closer Look at the SPAT Devices Bundle

There’s nothing quite like the intimate sound of a live performance. The immersive feeling of being in the same space as the sounds you're listening to – hearing the music interact with the objects, surfaces and other people in the room – is a big part of what makes the experience so special. And it leaves many music makers itching for tools and techniques to recreate the same sense of closeness in their own productions.

But it’s an extremely difficult feeling to recreate, even with modern audio software. Maybe you’ve tried it: you pan an instrument off to one side, adjust the gain, add a decent reverb and hope for the best. It’s not bad, but it’s not great – you and your music are still clearly inhabiting different acoustic worlds.

Enter the SPAT Devices bundle, a collection of two spatial sound Packs by Music Unit, produced in collaboration with the IRCAM institute. Both Packs – SPAT Stereo and SPAT Multichannel – are equipped with interactive sound localization tools, quality reverbs that can imitate the acoustic qualities of rooms, and advanced panning algorithms that faithfully reproduce realistic listening scenarios. The Multichannel Pack takes things one step further, letting you take full advantage of SPAT’s spatial technology by sending audio to more than two speakers (up to 32, to be precise) in dozens of customizable configurations.

The multichannel setup in Music Unit’s studio

For Manuel Poletti, one of the researchers behind SPAT Devices, early experiences with immersive performances sparked an enduring fascination with spatial sound and multichannel audio:

“The first time I heard anything you could describe as multichannel was a modern percussive classical performance. I was amazed that the sound was coming from everywhere. That’s the memory that excites me, and so does the idea of reproducing that in a venue or a studio.”

Background

The Spatialisateur project – also known as “Spat” or “SPAT” – started in 1991 as a collaboration between Espaces Nouveaux and IRCAM, with the goal of developing a virtual acoustics processor that would allow composers, performers and sound engineers to control the diffusion of sounds in real or virtual spaces. The project stems from research carried out within the IRCAM room acoustics lab on the objective and perceptive characterization of room acoustic quality, and incorporates research done at Télécom Paris on digital signal processing algorithms for the spatialization and artificial reverberation of sounds.

How it works

In basic terms: the Spatialisateur processor receives a sound, then adds spatialization effects in real time before producing signals for reproduction on an electroacoustic system (speakers or headphones). What makes the technology special, though, is that it lets the user control the sound from the point of view of the listener, rather than from the perspective of the sound source. Practically, that means three things:

Perceptual control: the sound source, the artificial room effect and the relationship between them can be controlled in terms of perceptual attributes rather than the actual technical characteristics of the space – dimensions, materials, and so on. The user has access to parameters like “Warmth,” “Brilliance” and “Room Presence,” all derived from psychoacoustic research carried out at IRCAM, that put the focus on the way the sound is received rather than the way it’s generated.

Versatility: the desired effect is independent from the reproduction setup, and is (as much as possible) preserved from one listening environment to another. Used correctly, the amount of adjustment needed to get a similar sound out of the SPAT Devices with a set of headphones or a set of speakers is minimal.

Simplicity and precision: unlike systems in which the localization of the sound and the reverb effect are kept separate, the Spatialisateur processor combines the directional and the temporal aspects of the listening experience. This allows for more precise and intuitive control over the distance or proximity of your sounds.

The panning algorithms

Standard intensity panning – also known as “angular” panning – involves simply adjusting the gain of either the left or the right channel, resulting in a sound that is literally angled to the left or right and nothing more. It’s easy to use and understand, and it’s what most music-makers are used to. But it’s no match for more advanced panning methods that simulate realistic listening scenarios.

The first three panning algorithms in Spatial Stereo (“AB,” “XY” and “MS”) recreate realistic microphone setups, typically resulting in less drastic dropoffs when a sound is panned to the left or right (in these setups, a sound panned all the way to one side will still be picked up faintly by the microphones it’s furthest from). The multichannel version of Spatial has its own panning algorithms – “Nearest,” for situations in which no particular “sweet spot” is required, and “Ambisonics,” which results in greater stability of the sound scene.

In Spatial Stereo, the real magic comes with the “Binaural” and “Transaural” modes, which are designed to recreate the feeling of being in the same room as your sound source. “Binaural” mode – intended for headphones – uses HRTF filtering to simulate the unique acoustic effects of sound waves reaching the outer ear, before interacting with the cartilage and passing into the ear canal. A mannequin head (and sometimes a torso), complete with ears made out of flesh-like material and microphones where the eardrums would be, is typically used to capture a snapshot of the sound properties in the form of impulse responses. Among other things, the sound is affected by the “shadow” that results from the listener’s head blocking a direct path between one ear and a sound source – as well as by the vibration of the sounds through the artificial head and torso themselves.

“Transaural” mode, meanwhile, decodes the algorithm to get as close as possible to the same effect with a pair of speakers. Manuel explains:

“The idea is to try to reflect your morphology according to the speakers’ positions. Some masking effects appear – for instance, a speaker on the left will reach your left ear first. For a static listening position, you can imagine a 3D sound out of two speakers. You can have really huge panning that goes 120-30 degrees wide, which results in a feeling of envelopment and movement if you move sounds around.”

The combined effect is a listening experience that’s uncannily close to being in the same room as your sound sources. In Spatial Stereo, it’s best heard on headphones by slowly moving one of your sound sources in a circular pattern.

Multichannel

For artists, producers and sound engineers who want to work with more than two speakers – whether it’s for creating surround-sound film soundtracks or writing music for sound installations – SPAT Multichannel offers even more. It brings multichannel functionality to all of the devices that come with SPAT Stereo, as well as a dedicated Speaker Editor that allows you to map and customize your configurations, dialing in delay compensation for total accuracy.

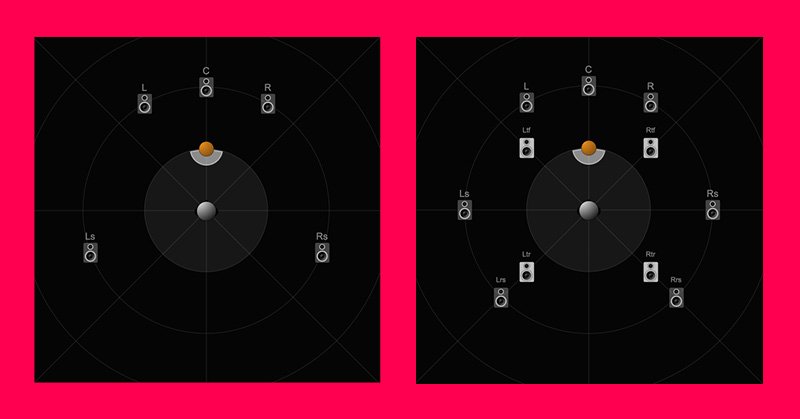

Two of the configurations possible with SPAT Multichannel – a simple 5.0 setup (left) and a Dolby Atmos 7.0.4 setup (right)

For Manuel and his colleagues, the ultimate goal of the technology is to blur the artificial boundaries between sound and listener and create more embodied listening experiences:

“We have a sound garden in a bay in Paris with 32 speakers, and we hold concerts there. It’s like an environment. You’re listening to music, yes, but you’re also listening to an environment. The divide is simply not there. It’s natural, it’s relaxing. You can breathe. It can be very powerful.”