If the idea of protest music was popularized by folk singers in the ‘60s, like music itself, many more forms of it exist today. And while it should not be necessary to explain why artists make protest music – racism, sexism, and concern about the brutality of global economic systems are a few reasons that come to mind – it’s a clear source of inspiration.

But what to do once that energy is harnessed? Singers usually have the benefit of lyrics and verbal narrative to get their message across. But electronic artists working in primarily instrumental music have to get creative. In order to learn more about the different shapes aesthetic protest can take and some of the thought processes and methods used to achieve them, we talked to a number of artists whose work doubles as social commentary and critique.

Lotic

When I interviewed the Tri Angle-signed, Berlin-based, American producer Lotic, aka J’Kerian Morgan, in 2015, he told me, “I wanted to be loud and upfront about being a black, gay male through my art, not just saying it in interviews every time.” When listening to his striking productions, one gets a sense of alienation, anger, violence, excitement, and wonder, usually within one track.

Speaking to him again about how standing up for his identity shapes his music, he explains, “I try to make the music that I like, but I also try to make music that I think people don't necessarily associate with the idea of ‘black musician,’ or ‘gay musician.’ I think it's important to fill this void, and normalize blackness. There also are specific struggles that I have to deal with on a daily basis – literally, even if I don't leave the house – that I try to embed in the music. Little things dealing with being not just a gay man, but a feminine gay man. Especially from within the gay community, the misogyny is insane, as is the racism. I just try to put it all in there.

“The track "Trauma" is dealing with the daily micro-aggressions. Someone poking you with a pin every single day, you're going to eventually have scars. With that track, I found a silly dubstep sample or something, with a kick attached to this sort of screech. The effect that I put on it made it sound like an actual vocalized scream. Yes, it's obvious, but I felt I needed to do something that was a little more obvious to get this idea across. Also that melody is a very horror movie situation. I opened an EP called Agitations with a track called "Trauma", so it was very intentional.”

Like much of Lotic’s music, “Trauma” feels on one hand attractive and intriguing, and on the other hand, confusing or unknowable (the latter can also serve the former, of course). Morgan agrees: “Yeah it's true. I want you to pay attention, but I still want there to be distance. I think that's literally how most of my interactions go. Maybe not as much now, but when you're raised by a black mother, she's always telling you, ‘Be careful of trusting people, because people don't trust you,’ along with things like, ‘Don't get pulled over, comply with everything.’” Morgan also agrees that the idea of social commentary is innate to his music, admitting, “I can't be another way. I think it's happening for me more now that I live in Europe, because I don't have a black community per se to turn to to talk about these things. Because I'm dealing with these things internally, they're going somewhere, so it ends up there. I think anyone that has a platform, to not use it is irresponsible. [laughs] But at the same time, I think a lot of people, the majority of the industry, don’t have to deal with a lot of these things, so they don't have anything to say about it. They don't have anything to say about anything.”

Peder Mannerfelt

As a native of one of the world’s wealthiest nations, one that has enjoyed peace for over 200 years, it would have been easy for Sweden’s Peder Mannerfelt to be one of those people with no real complaints. Instead, his track “Limits To Growth” – from the album Controlling Body – shows another manifestation of his political conscience: namely, in questioning the unsustainability of the capitalist model of infinite growth. As he explained at last autumn’s Loop conference, thinking about this led directly to the track’s monolithic production, its slow evolution, and the resulting sarcastic neoliberal mantra of the sampled vocals.

Ziúr

Berlin-based producer Ziúr shares Lotic’s feeling that politics are innate to her identity. As a trans woman, she says, “My mere existence is political.” But as she clarifies, “It's not like I specifically write tracks with a message. More like, on a sub-level, my music is an expression of how I am functioning as myself. Like a third leg or something, it's just part of me. Because I do see myself as a political being, and I think it's super important for me, in my life, and this world.”

For Ziúr, the understanding is there from the outset that not everyone is going to get either her or her music. “I don't need to talk to everyone,” she shrugs. “Maybe sometimes I’ve had the idea of trying to be more accessible with my music, but then I figured that’s not the way to go. I don't want to compromise on that. It creates access for some people, and it doesn't for others. But I think that people that have access to it, can identify even more with it.” Similarly, discussing gender as a topic is only something she feels comfortable doing with certain people: “I don't want to talk about it, if I get the feeling that there's no common ground.”

But perhaps her music can help to create that common ground. “There’s definitely that chance,” she muses. But as Ziúr, she’s using a soft touch to accomplish that: “If you're not preaching or making people defensive, that's usually the better way. Because then, they’re more likely to get it.”

Mat Dryhurst

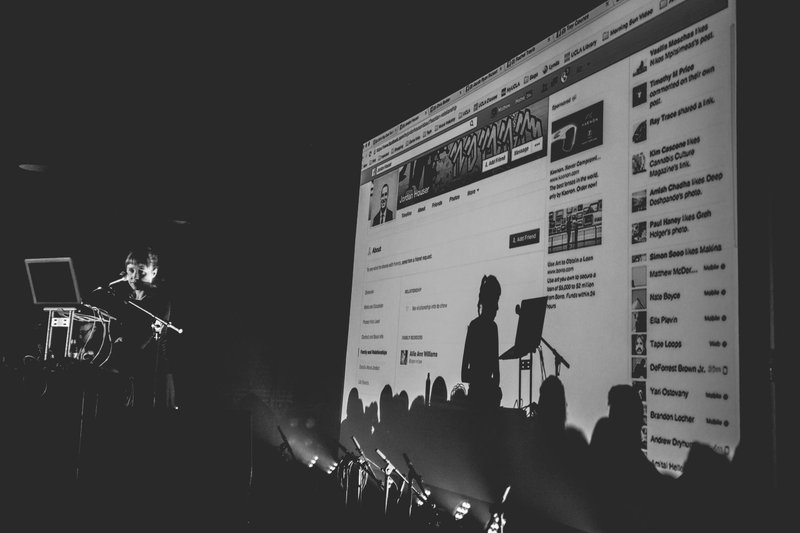

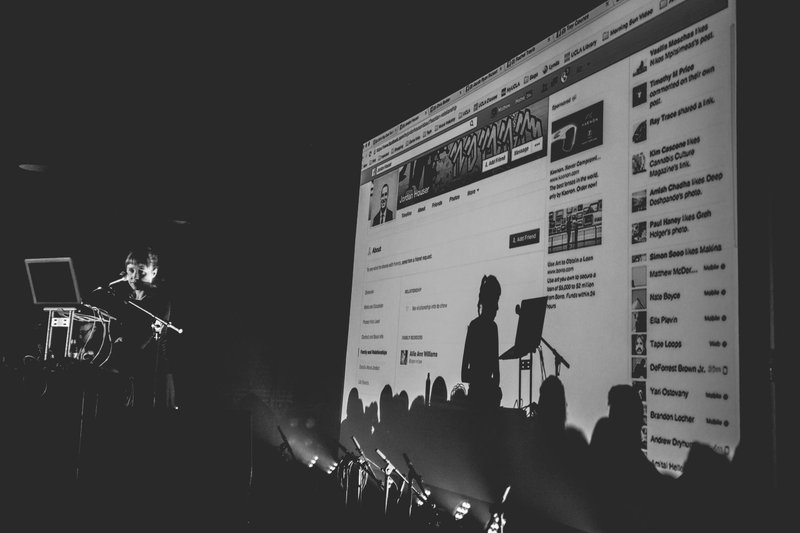

Mat Dryhurst is best known through his work and relationship with Holly Herndon, where the two regularly embed a message in the music, often overlapping with technology. While they regularly spoke out in plain terms for the release of whistleblower Chelsea Manning, Dryhurst’s practice as a multi-disciplinary artist has addressed similar concerns in less direct ways. For instance, as he explains over email, “I’ve done a lot of data mining works. Initially, I would use advance knowledge of [concert] attendees to tailor performances to who was going to be in the room – the most apparent function being a means of confronting people with an invisible reality of data tracking. Is congratulating people on their new job on the walls of Berghain appropriate? There are all sorts of new questions around data and how we interact with each other; on the most basic level we have all experienced meeting someone for the first time who we know a lot about from going deep online, and the parameters for what is appropriate or inappropriate in those scenarios are unclear and worthy of experimentation. I think those performances initially worked well when there was an element of surprise, but then stopped doing them when they became an expectation, as I don’t want it to be a party trick.

Mat Dryhurst used audience data mining as part of Holly Herndon’s live performances

“I have also made a couple of audio plays, with the idea being that I would data-mine the audience in advance, and write the narrative to subtly reference things from their lives. I did a piece for a small group, called MINE, that worked really well for this. I would incorporate traces of the Chinese restaurant next to the high school someone went to, or a famous local event from around the time someone was growing up, in order to see how this form of subtle manipulation affected their experience of the story. I later did one of these plays, MUSTER, with a large data set of listeners from Deutschland Radio Kultur, and had to abstract the themes a lot more to factor in a larger group of listeners. This was tougher, but still rewarding.

“With companies like Netflix as harbingers, personal data driven culture is here to stay. My fear is that it’ll be hard for people on the margins to compete unless we figure out our relationship and boundaries toward the concept.

While his data mining works address the topic of digital privacy in a playful way, Dryhurst also launched a project called Saga, which deals with the cut/paste/copy/reblog nature of the web. As he describes it, “Saga is a publishing system that offers an artist control of every individual instance of their work online. This opens up a bunch of options for what I call website specific performance, where you can basically take over any space in which your work is hosted – take it down, alter it, respond to its environment – without affecting the other versions of the work online. I had initially been approached to make a record, and then in asking myself what ideally that might look like, I came up with this idea of wanting the ability to communicate through my work to individual people, which was consistent with the data pieces I’d been doing. That technology didn’t exist, so I had to put it together.

“I want the things that I do to be alive somehow. This also seems of some political value, as Saga means that a piece of work can talk back to its environment, and not be misused. I’ve had people approach me to say that academics ought to use it as a way to correct articles where their research is being misinterpreted, for example. Once you understand the logic, it’s quite powerful.

Saga allows artists to track where their work ends up online and make alterations, such as the text overlay above.

“Take, for example, this interview scenario, which is hosted by Ableton. My assertion is that my gestures online ought to have the same agency as I have in person. If you were to post a Saga embed here, I would have that space to do whatever I wanted on their page. Some people are really uncomfortable with that, which I understand, but we learn from those tensions. In another context, for example, is it possible to sell ads next to a piece of music that might make fun of them? What would happen to ad-driven media if we all decided to publish this way?” While Saga has yet to reach its full potential, given the existence of a web annotation service like Genius, it feels like a necessary counterweight to preserve a creator’s intent.

NRSB-11

In 2013, DJ Stingray and Gerald Donald (of Drexciya, Dopplereffekt, Arpanet, Japanese Telekom, etc.) released their collaborative album as NRSB-11. While the two electro masters and old friends from Detroit had released a self-titled EP the year before, Commodified’s album title and succinct track titles – such as “Consumer Programming”, “Living Wage”, and “Market Forces” – made a strong statement about capitalist consumerism.

As Stingray (aka Sherard Ingram) tells me via email: “The music was started first then the concept developed. We exchanged short musical ideas, enhancing and expanding on some while discarding others. We would have regular discussions and critiques, suggestions. etc.”

While Ingram is wary of the term “protest music,” he readily admits that there’s more to the project than your average techno record. “I try not to stand on a soapbox or do armchair activism,” he cautions, before revealing another layer to the music. “I just [try to] provoke a little thought, and add depth to my projects with the goal being to move electronic dance and experimental music in a direction that serves as inspiration, possibly a catalyst, or soundtrack for progressive paradigms. We should strive to be a serious part of people’s musical lives.”

Chino Amobi

As the co-founder of NON, the collective of African diasporic artists with a fiercely political mission statement, Chino Amobi has created an entire framework around his music in protest of existing power structures. Fittingly, we see this kind of holistic vision as it applies to his work in this clip from Loop, where he describes the processes behind his track “Milan”, from the album Airport Music for Black Folk. As he explains, the entire album consists of sonic representations of specific airports through the experience of a person of color.

Elysia Crampton

Like Ziúr, Elysia Crampton’s mere existence is political, and the complexity of her music is an indication of the depth of her themes. Speaking about her track “Petrichrist”, she explained at Loop that it first represented a journey, but then became a reconciliation of two notions of her relationship with God/god-ness. More intriguingly, she prefaces the explanation by pointing out that much of what musicians may be writing ‘about’ can’t be expressed fully in another way, meaning that sound and music are legitimate, and necessary, registers of the political. Whether or not music contains lyrics or a vocal narrative, artists will always find ways to give voice to grievances, concerns and critiques – most powerfully in the space where the political becomes personal.

Text and interviews with Lotic, Mat Dryhurst, Ziúr, and DJ Stingray conducted by Lisa Blanning