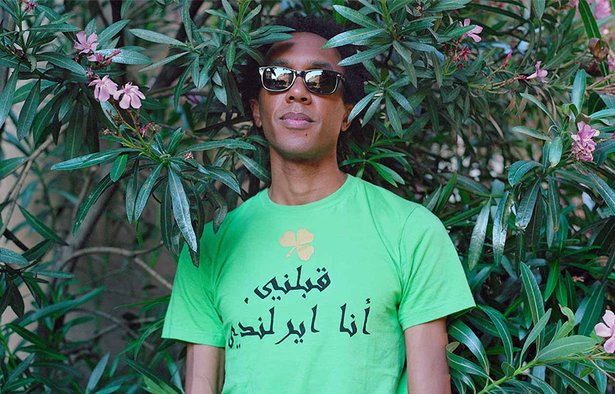

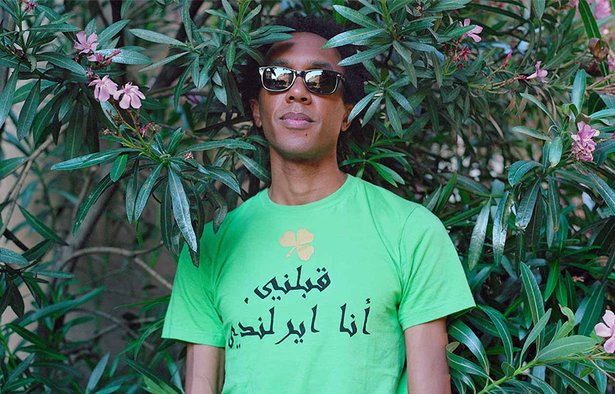

Jace Clayton, also known as DJ /rupture, is an eclectic, ambitious musician with ears tuned to the workings of sounds in their native habitats. His output is extraordinarily worldly, inclined toward unorthodox mixtures of sounds he first enlisted on Gold Teeth Thief, a DJ mix he made and released online in 2001. The playlist proved a prescient sign of the times, with hybridized, genre-mashing combinations of Missy Elliott, Middle Eastern music, spastic drum ’n’ bass, reggae, and more – often all spun at the same time. Before such stylistic interplay was the norm and online DJ mixes became routine, Gold Teeth Thief was a jolt whose after-effects are still being felt.

Clayton has continued his work as DJ /rupture ever since while also working in other modes. He has found success as a writer, for magazines and journals as well as a book to be published next year. He has worked with a live band called Nettle and, under his birth name, made an album in tribute to the radical avant-garde composer Julius Eastman. He also created software for a mindful project called Sufi Plug-Ins, which offers plug-ins with unusual sounds for free download online.

Here, from his home in upper Manhattan in New York, Clayton talks about his diverse body of work and ways it all becomes interconnected.

At the beginning, when you made Gold Teeth Thief, what was your process like compared to how you might make a mix like that today?

It’s funny because the technical process isn’t so different. The nuts-and-bolts of it is just recording mixes live. I did that in two takes, recorded to MiniDisc. That was before Serato and all that stuff, so it was just vinyl and a few tracks on CD. Culturally, I feel like so much has changed. The type of mixing I was doing then was very new to most people – that’s why I’m here, in a way, because it spread so quickly. Making those kinds of connections and leaps and superimpositions has almost become a mainstream approach to DJing. It also made more sense to do a mix back then – there weren’t many DJ mixes online. So many people downloaded Gold Teeth Thief as this crazy word-of-mouth thing, but I was living in Madrid and just wanted my friends to hear it. So I made a CD and sent it to a friend and asked if he could rip it and stick it somewhere on the web for me.

Do you think some of the charge of such stylistic promiscuity has diminished since then, with open access to everything and so many genre lines now blurred?

I do. It has changed, and it’s hard to tell how. For various reasons, people are used to ‘like and unlike’ occupying the same space now. It’s interesting: when people sit down to start working, I wonder what is going through their minds and how they are positioning themselves, what they are thinking. When everything is there, what’s the next step?

What is the nature of the book you’re working on? It’s been described very basically as about “21st century music and global digital culture.”

I don’t have a title for it yet, and I’m reluctant to talk too much about this thing that has no title, but it will be published in July 2016. It’s thinking about the last 15-20 years and all these technological changes – mp3s, inexpensive laptops, networked listening – and people who are taking advantage of the new conditions to create and experience and share music in unprecedented ways. I’m drawing on myself and my travels. I’m very interested in grassroots technology, and it has a global grassroots perspective in it. It’s not an academic book – I want it to read something like literature, where you get to go to a place and zoom out and think about what it all might mean. One of the things I reflect on is spending time in a Palestinian refugee camp in Beirut. It wasn’t in a political context – I was in Beirut for a gig. That’s the kind of approach throughout the book: to wonder what these changes feel like, and not just from a technological perspective. So much writing about this kind of stuff is industry-focused, like Where is the money going? And what about streaming? So of much of those debates I find incredibly boring and uninteresting.

Your Sufi Plug-Ins project is interesting for how it has wandered extensively around the world. How did that project start?

I was living in Spain for six years and working a lot with this Moroccan violinist named Abdel Rahal. He was in this band project of mine called Nettle. It was very interesting for me because I’ve been a fan of Moroccan music for ages, but then I realized, living in Spain, I could actually work with Moroccan musicians and take it a step further. In our initial sessions I realized the differences in scales. He was comfortable with all sorts of Arabic quarter-tone scales and could go in directions that synths and gear didn’t readily go. And of course there was all these beautiful, supple polyrhythms in Moroccan music, and computer sequencers are not about polyrhythms – they’re meant to be 4/4, 6/8, a very square approach to time. It all also worked on the flipside. I remember playing Abdel a hip-hop beat that I was working on and, when I asked him to play on top of it, he was hearing it in a completely different way. He was hearing a complexity that wasn’t there and riffing off that. I was like Wow, these are interestingly different universes.

How did you conceive the Sufi Plug-Ins to address that?

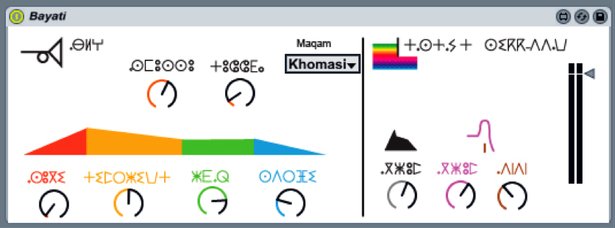

It would create a friction to work with Abdel and to try to get acoustic and electronic sounds more closely intertwined. We realized how few tools there are that come from a non-Western perspective. In the beginning, it was just to make some things we could use in performance. But it’s always interesting to give something away for free. When you buy something, you ask What is this? What am I getting? What is the customer support? But I realized if we gave it away it could be like an art piece. I could create an interesting interface with a beautiful old Berber script – it’s 2,000 years old – and put in all this weird poetry and not explain it. I could have it be this real experience that people engage with.

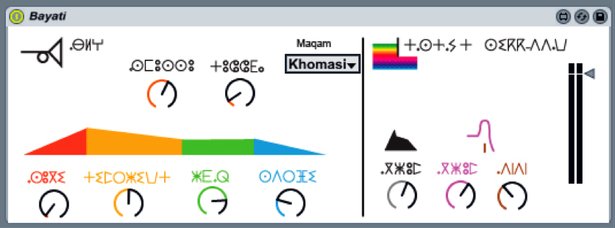

The Maqam synthesizer Bayati

The interface includes bits of Sufi poetry where simple instructions or labels might otherwise go. How did you collect those?

I was collecting poetic fragments. There’s an enormous legacy of Sufi poetry. In the plug-ins, everything you can hover over [with a cursor] has a pop-up bit of poetry. Software is so literal and so square: it’s all grey boxes, everything is rectilinear, you hover over the volume fader and it says “VOLUME.” I thought: let’s have it say something else. It’s a random assemblage from poetry books and some online research. Rumi is the most famous Sufi poet, so some are the same two lines from him but through 400 years of translation into English. Some of them rhyme, in some of them there’s god, others are totally secular. It’s wild to see the variations from Persian to English.

The Palmas clapping drum machine

The Sufi Plug-Ins work in a variety of software environments. Did you have Live in mind while making them?

It’s interesting: I didn’t actually start the project until MaxMSP was put inside Live with Max for Live. Max is a very interesting programming environment. I’ve done some plug-ins that get real-time data from the stock market and translate that into specific musical information. That’s the sort of thing you can do in Max relatively easily. You need to be a programmer, but it’s very good for doing just really weird stuff like manipulating data into sounds in interesting ways. But it’s also very unwieldy. You open it up and it’s just boxes and lines—it’s not user-friendly. So when they made that able to go inside Live, all of these people coding weird objects in Max could have a container for it and it became a more user-friendly program.

How do you use Live otherwise?

I have used Live for production, as a production environment. In my band Nettle, it’s my main live tool. When I do the Julius Eastman Memorial Dinner [the performance incarnation of his album The Julius Eastman Memory Depot, in tribute to the late New York-based avant-garde composer] I use Live to do the live processing.

You’ve talked in the past about how most music software is made in the U.S. or Germany.

So much software use is informal, with people getting cracks. But spend time in Egypt or Bolivia and you see kids who can’t read a word of English watching videos for how to make a beat in Fruity Loops and trying to figure out their way around software that is kind of totally hostile to their language environment.

You’ve described the Sufi Plug-Ins as an antidote to that, to bring new, culturally relevant sounds to the Middle East and Africa. Do you also want to steer those sounds elsewhere?

It’s music software as art, so it’s a very specific experience urging the user in very specific ways. But I like the idea of it circulating as widely as possible. It’s a space of possibility. Software doesn’t have to be this thing that comes from up high and is handed down to you and you figure out how to make whatever you want to do fit into it. Of course there are worlds of creativity within that, and we all love that, but I would love to see a world in which creative digital tools have a sliver or a fraction of the wildly localized aspects of actual tools. With musical instruments, everywhere you go, people use different instruments in different ways. And then in software there are just like a half-dozen platforms. It’s a huge amount of creative energy and modes of expression that are being funneled through a tiny little spigot. People like the plug-ins because they’re so out-there and unlike everything else available. Hopefully they take that as inspiration.

Jace Clayton aka DJ /rupture is among the participants at this year’s Loop, Ableton's Summit for Music Makers.

Keep up with Jace Clayton via his blog and download the free Sufi Plug-Ins.

Photos by Xabi Tudela and Erez Avissar