Aho Ssan: Sound from inside the Rhizome

Community is a fluffy word. It sounds welcoming and brings to mind groups of people supporting one another with smiles, pats on the back and encouraging words. The reality can be quite different. As much as you may want to be part of a community, sometimes there’s no easy way in. It takes time and effort and French producer Niamké Désiré, AKA Aho Ssan, knows this.

His route into the underground electronic music scene has been an unconventional and determined one. He came across Max for Live while he was studying MPI (Mathematics, Physics and Computer Science) at l’Université d’Orsay. At the time, he had no aspirations to become a producer, focussing his attention to film instead. But Désiré soon realized that making films would be tricky to do alone. “You need a bunch of people [to make films]. You can't do it by yourself,” he tells me over Zoom from his flat in Paris. “With music, it’s really easy to do your own thing.”

Désiré is no recluse, he just didn’t know anyone who worked in music production. “I was lonely in my reality,” he says. “Being a black artist doing experimental music in France, I didn't have a lot of other black artists to look to.” It wasn’t until he read Simulacra and Simulation by French philosopher Jean Baudrillard that he considered going it alone. In that book, Baudrillard argues that, with the rise of technology and mass media, we have become so far removed from objective reality that any notion of reality is redundant. What is real to you might not be real to me, for example. If this is the case then each person’s reality is as malleable as they want it to be. So in one reality, Désiré is an outsider to the world of music production, alone, and with no support network to help him, but in another, with tools like Max for Live, he is an experimental electronic music producer with enough tools to make his own orchestra. “I’m not a musician but the computer helped me to be a musician in a different way,” he admits.

In 2019, Désiré released his debut album Simulacrum on James Ginzburg’s Subtext Recordings label. It’s the first example of Désiré’s unique composition style – seemingly built on electromagnetic tendrils that spread across each track like moss across a forest floor. This musical fabric is inherently frayed: it quivers under the slightest quake of sub bass and dissipates no sooner than it’s made. It’s almost as though a sense of imposter syndrome comes through in the composition’s loose texture. In spite of these threadbare foundations, there are some obvious musical elements in there, if you listen out for them. In the haze of “Intro” and “Outro”, gently blinking brass toys tentatively with major key notes as though moving towards something bolder and more hopeful. To get this imitation of brass-playing, Désiré used Max for Live to imitate the musicianship of his grandfather, Mensah Antony, who was a trumpeter in a Ghanaian jazz band in the 1950s. Désiré never knew his grandfather, but from speaking with family members he heard of peculiar stories that would inform the patches he made on Max. One story involved family members claiming where they’d seen Antony’s trumpet, some joking that it was last seen in a cave. This, along with his grandad’s love of American space-jazz bandleader Sun Ra, evolves to give the brass an ethereal presence on the LP, one that both reflects Désiré’s distant relationship with his grandad as well as aptly represents the piecemeal memories of him that live on.

Simulacrum is a triumph of imagination and resourcefulness, proving what one person can accomplish with just a computer and a few devices. In many ways, though, it wasn’t a lone venture. Besides looking to Baudrillard’s philosophy for inspiration, Désiré credits a lot of his artistic ideas to the everyday conversations he has with people. He explains: “I feel like the conversations I'm having with people is something you can't imitate with a computer. I’m talking about conversations before making music – like when I was working at the Louvre Museum, I was not talking about music with the people working there. I was talking about a bunch of things – just life. And that's something I can't do with a computer.”

In the wake of Simulacrum and the pandemic, Désiré toured his project around the world and met other like minded musicians. After one show at Donaufestival in Austria, the festival promoters asked him to return the following year with something along the theme of cultural appropriation. “And I was like, that's really crazy because I'm reading an amazing book right now (sort of) about it – Glissant's [commentary] on rhizomes.” Edouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation delves deeper into the topic of rhizomes established by French philosopher Gilles Deleuze’s and French psychoanalyst Felix Guattari. A rhizome is an “enmeshed root system, a network spreading either in the ground or in the air, with no predatory rootstock taking over permanently. The notion of the rhizome maintains, therefore, the idea of rootedness but challenges that of a totalitarian root.” It’s the opposite to a hierarchical (arboreal) root that has a bottom and a top and which Glissant likens to a Western colonial root that spreads across the globe and imposes its way of being and thinking onto foreign countries and cultures. He calls that “arrow-like nomadism”, and contrasts it with a rhizomatic approach, a “circular nomadism” – an errantry – which “conceives of totality but willingly renounces any claims to sum it up or to possess it.” Imagine this personified as someone who, as well as being curious to connect with places and people different to themselves, knows and accepts that they may never fully understand the other and so never attempts to generalize or force their presence upon them.

With Glissant’s rhetoric in mind, he approached Chilean-American composer Nicolas Jaar – who he had recently put together Weavings – a project with similar rhizomatic themes – and asked him if he would be interested in supporting this new project; Jaar agreed. Désiré’s second album, Rhizomes, came out last year and features artists who he met either through Jaar or on his travels touring Simulacrum. The record is a direct development of Simulacrum since Désiré no longer has to mimic musicians. But rather than simply rely on his collaborators and call that rhizomatic, Désiré embraces the concept like a method actor. He tells me about his collaboration with Blackhaine, for example, which begins as you’d expect: producer sends instrumental to vocalist, vocalist records over the top and sends it back for the producer to finish. But when Désiré returns his finished piece to Blackhaine, Blackhaine decides to start all over again. "I had to be OK to lose the control in order to be really into this rhizomatic thing and I was really happy to do so because I love what all the artists do,” he explains.

In fact, the more you delve into Rhizomes the more it becomes about the other artists than it does Désiré. The physical record comes with a book which features lyrics to the tracks alongside curious line drawings by illustrator Kim Grano that bring to mind the alien language of the heptapods in the film Arrival where whole sentences are contained in one circular brush stroke. There’s also QR codes lurking inside the book’s pages that lead to bonus tracks for the album as well as solo tracks made by some of Désiré’s previous collaborators, like KMRU. And the physical release even invites listeners to get involved in the rhizome by providing a pack of samples (made by Désiré) which they can use in their own music production. Where he may have relinquished some control working with Blackhaine, with the sample pack Désiré lets go completely.

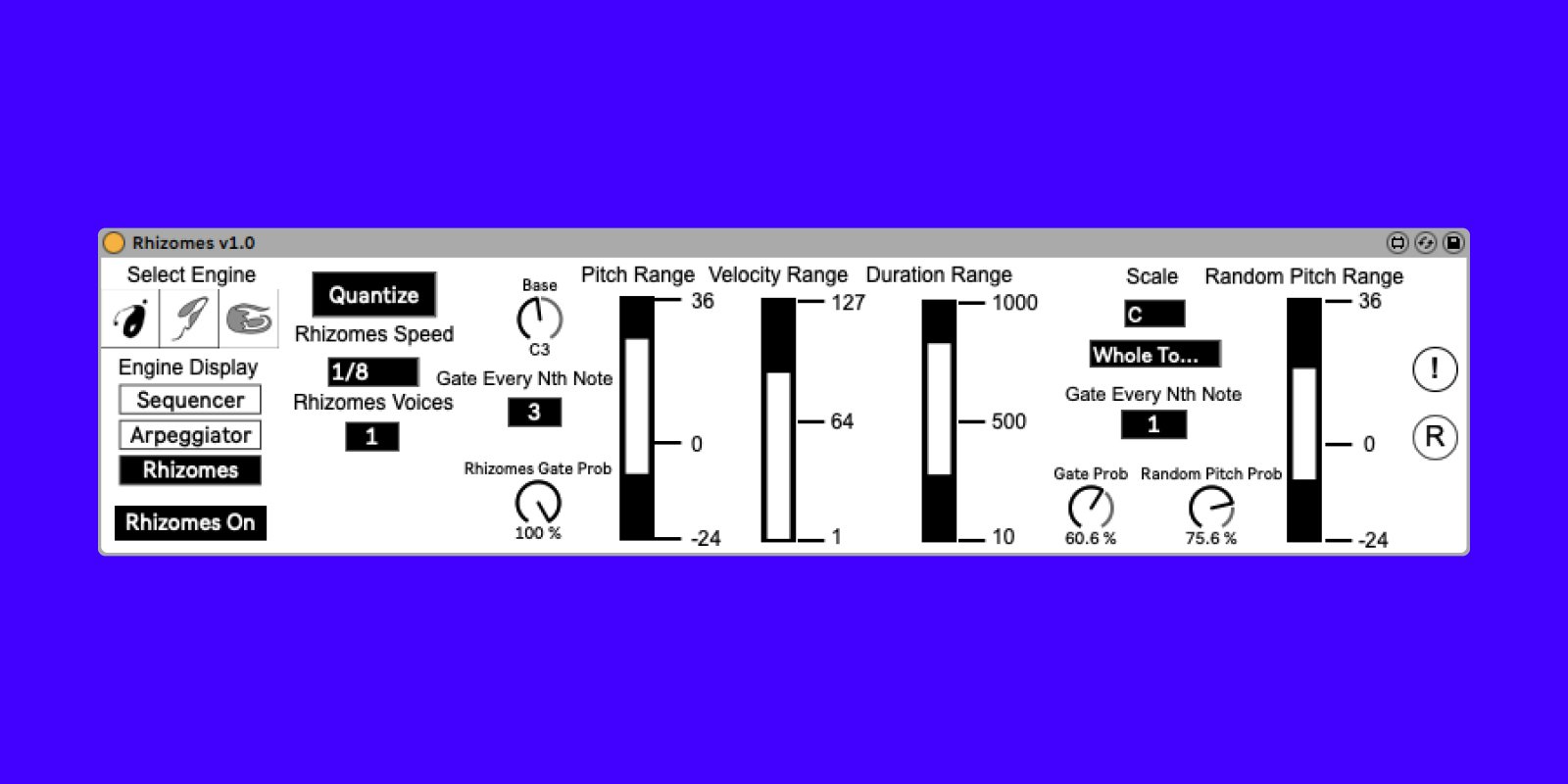

And he continues to do so. He kindly agreed to create a Max for Live patch exclusively for this article with the help of his friend Michalis. Loss of control and randomness plays a huge part in the function of the device which has three features: sequencer, arpeggiator and rhizome. The rhizome, as Désiré explains to me in a tutorial video, works much like a root, playing random notes around the set of notes you generated either with the sequencer or the arpeggiator. And while he admits that this may not seem very musical at first, you can then record a section of the rhizome device’s random notes in search of a pattern or set of notes that you could use to forge something musical. And this is what Désiré and Michalis want to encourage users to do – to listen closely to what the device is doing rather than blindly follow a set of rules to get quick results. “It’s a device where, if you're curious and you want to do something less grounded, it's perfect,” he says.

Download Rhizomes 1.0 device

Requires Live 11 Suite or higher. Upon loading the Rhizomes device in Live, click the “!” button for info and use instructions.

Follow Aho Ssan on Bandcamp and Instagram

Text and interview by Joseph Francis

Photos by Marvin Jouglineu

Rhizomes device by Voim Ateri & Aho Ssan