Unheard Brazil

With the eyes of the world turning to Brazil for the 2014 World Cup, we thought we’d take the opportunity to shed some light on the country’s musical landscape past and present. Of course, with a populace so diverse, spread across a territory so vast, Brazil’s musical heritage is not just one, but a multitude of streams that continue to flow and feed into the country’s present-day music scenes. Over the course of three articles we’ll be sharing some of our favorite innovative Brazilian music from the past, talking to renowned veteran producer Dudu Marote, and surveying the current crop of artists bubbling up from the Brazilian underground.

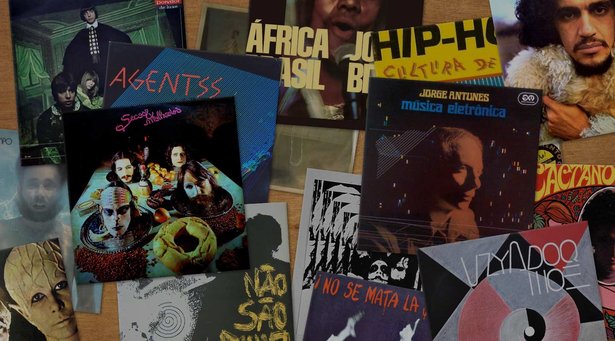

Let’s start with a refresher course of sorts. We’re all familiar with samba and bossa nova (at least as drum machine presets), and in more recent years the sounds of modern baile funk and vintage tropicalia have found their way onto dance floors and into tastemaker playlists across the global North. Since you’re reading this here, we’re assuming that you are interested in a) electronic music b) interesting studio techniques c) stylistic innovation, or all of the above. With that in mind, we’ve selected a sampling of our favorite Brazilian tracks from the 60s, 70s and 80s – all of which defy narrow expectations of what Brazilian music ‘should’ sound like.

We begin with a pioneer of electronic music in Brazil, Jorge Antunes. In 1961, at the age of 19, he attended a concert by electronic music pioneer Karlheinz Stockhausen and Gottfried Michael Koenig, and was duly inspired to set up a studio in his parents’ house with a couple of reel-to-reel tape recorders and a self-built sawtooth wave generator. By the middle of the decade Antunes was splicing tape and had begun incorporating cardboard boxes, plastic containers, drums, theremin, tape echo and reverb along with piano and sound effects records into his compositions.

His remarkable 1969 piece “Auto-Retrato Sobre Paisaje Porteño” reads like a musique concrète history of Brazil itself. Beginning with what sounds like the din of the jungle, we soon find ourselves among cut-up loops of antique piano recordings. Gradually, these patterns merge with jaunty electronic rhythms, somehow reminiscent of both techno and polka. And that’s just the first three minutes.

By the late 1960s, the mixing of popular and avant-garde forms in music (as spearheaded by The Beatles) had found its Brazilian counterpart in the Tropicália movement. Among the best proponents of the movement’s eclecticism was the São Paulo band Os Mutantes (The Mutants) whose records blended rock instrumentation, vocal harmony, and studio effects all within unusual arrangements.

The video below shows Os Mutantes playing the song “Panis et Circenses” written by Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil – two leading figures of Tropicália. And although the version here is not as full-on psychedelic as the studio recording, this performance has all the hallmarks of a ‘60s classic (including one very fuzzy guitar and one very fuzzy vest).

Ever wonder where Kiss got the idea for their look? A persistent rumour has it that it was stolen wholesale from a full-page ad in Billboard magazine for the band Secos E Molhados. In 1973, they had just sold 1 million copies of their debut album in their native Brazil and were looking to break into the lucrative US market. Sadly, this was not to be, and although Secos E Molhados were (and lead singer Ney Matogrosso still is) huge in Brazil, the band remained largely unknown outside of South America.

Check out Secos E Malhados on Brazilian TV in 1973 lip-synching their way through the lovely “Sangue Latino”. The clip features Ney Matogrosso’s incomparable voice and the make-up that (perhaps) so inspired Gene Simmons and co.

Marcos Valle’s career began in the mid-1960s as a sought-after songwriter and singer. Having penned “Samba de Verão” – perhaps the definitive bossa nova tune – Valle went on to make a series of increasingly adventurous albums in the early 1970s. Previsão do Tempo from 1973 was particularly notable for its jazz-fusion feel and featured Fender Rhodes piano and Hammond organ prominently. Valle’s backing band on this record was Azymuth, whose keyboardist Jose Roberto Bertrami introduced liberal doses of Minimoog and ARP Soloist into the arrangements. Check out how the synths, floating gently over the melody make “Mais do Que Valsa” more than just a waltz.

After a fertile period of musical innovation in the 1960s and ‘70s, Brazil’s increasingly repressive military government had, by the early 1980s, squeezed much of the vitality out of Brazilian culture. The gradual return to civilian rule in the 1980s brought with it a reawakening of the country's musical life, but the sounds emerging now were increasingly urgent and angry – a far cry from the leisurely melancholy of “Girl From Ipanema”.

Whether by incorporating recordings of TV football announcers or just through a distinctive rhythmic sensibility, some of the most interesting Brazilian post-punk and new wave acts strategically deployed a certain refracted “Brazilian-ness”. Enjoy these two standout tracks from the 1980s São Paulo underground and see if you don’t think that Vzyadoq Moe’s dubbed-out “Redenção” sounds exactly like what would happen if Bauhaus played a samba parade.

Hip-hop, after breaking through to the mainstream in the US, quickly became a global phenomenon – with countless local and regional variations on the basic concept of rhymes over beats. Brazil was no exception and from the mid-1980s hip-hop crews in all of the country’s major cities began making themselves heard via mixtapes and compilations.

“Loucura” by Código 13, from 1988 is notable for being an early Brazilian hip-hop production by a certain Eduardo “Dudu” Marote – a musician and producer who went on to become something of an omnipresent figure in Brazilian music. Stay tuned for an in-depth interview with Marote next week. “Loucura” is also noteworthy for being a rare non-English language specimen of that short-lived, fast paced strain of hip-hop known as “hip house”. Check it while Código 13 wreck it:

World Cup Bonus Track:

Our vote for funkiest football anthem ever goes to Jorge Ben’s “Ponta de Lança Africano (Umbabarauma)”. Not about a particular team or even a real player, this infectious call-and-response groove beautifully encapsulates the idea of football as a communal experience.