A Brief History of The Studio As An Instrument: Part 2 - Tomorrow Never Knows

In Part 1 of our History of The Studio As An Instrument, we looked at the earliest pioneers of composing with recorded sound and traced some of the forerunners of modern sampling, looping and creative recording techniques. The story continues below with ground-breaking producers’ work finding its way onto television screens, commercials and to the top of the pop charts.

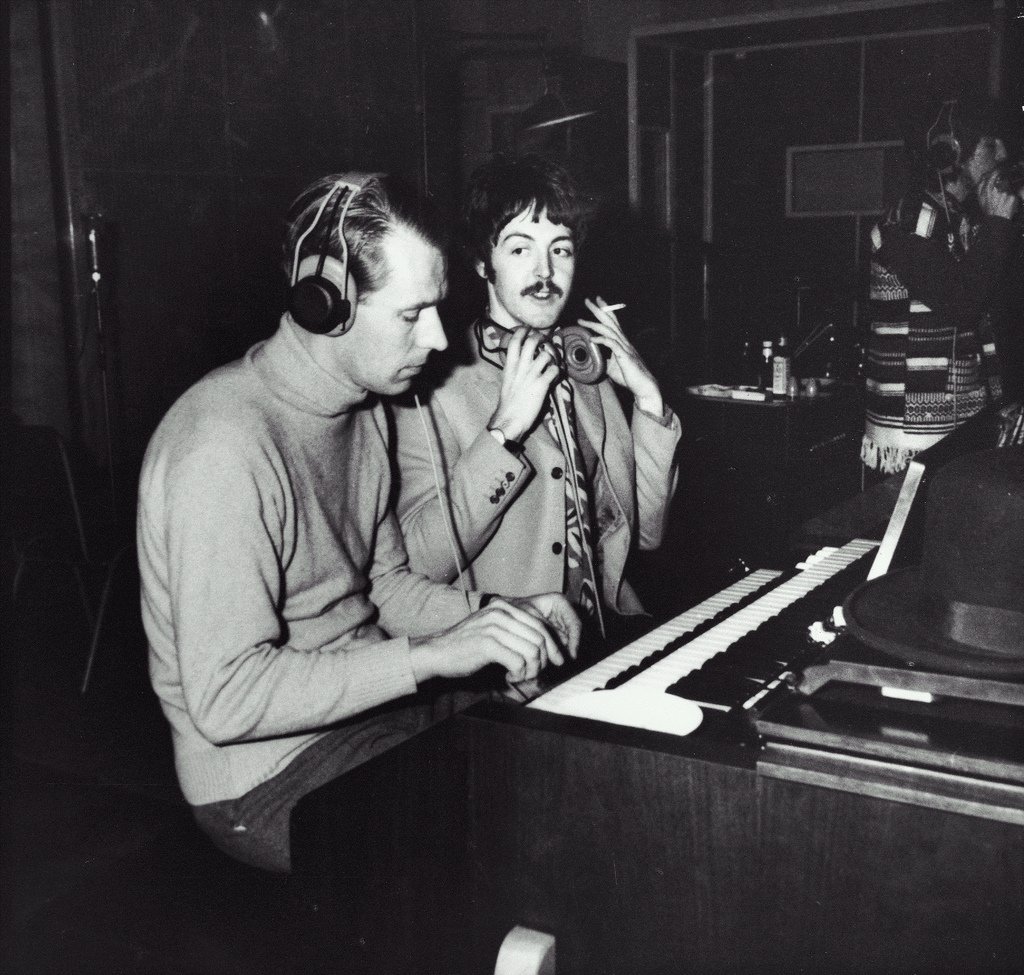

George Martin and The Beatles

George Martin at the EMI Abbey Road studios

It almost goes without saying that The Beatles are one of modern music's most influential groups. And this is not just due to the band's immense commercial success; the Liverpool quartet ushered in the British Invasion, brought psychedelic music to the masses, transformed pop music from a singles market to an album-based one, and completely eschewed every music business rule when they decided to no longer perform live, and only exist as a recording project. Perhaps then it should come as little surprise too that within the realm of studio and recording innovations The Beatles are also considered one of the most influential groups, in large part due to the visionary producer who matched the band's artistic visions with technical ability and inventiveness: George Martin.

Considered the fifth Beatle, Martin (who passed away early in 2016 at the age of 90) began working with the group in 1962 after having been a house producer for the Parlophone label working on jazz, skiffle, classical and comedy records throughout the late 1950s and early 60s. Soon into their partnership, Martin recognized that one of The Beatles’ strengths was their desire to constantly push themselves creatively, and so under his guidance the studio became a tool to express their ever more ambitious compositions. In particular, Martin began to see the multi-track tape machine as the best tool to achieve the sounds the group was looking for; much like the musique concrète pioneers, Martin understood that the tape machine was not just a static device for storing audio, but something that could be actively manipulated in the creation of compositions. An early example of this is the harpsichord-like solo that appears in the middle of "In My Life" – played by Martin himself, the solo was actually originally played on piano to a half speed recording of the song, but when sped up to match the rest of the song, the solo was imbued with a new tonal quality that made it sound much like a baroque harpsichord.

Producer George Martin occasionally played instrumental parts on Beatles Songs

Working closely with Martin, a growing awareness of the studio’s creative possibilities was took hold of The Beatles. On 1966's "Rain," Martin again played with tape speeds, recording the instrumental portion of the song at a faster than usual speed, and then slowing it down for playback to achieve a somewhat slurred, sludgy sound befitting of the stoned, meandering lyrics of the song. Martin also did the exact opposite with John Lennon's vocals, which were recorded at a slightly slower speed and then sped up for the final product. In addition, the song marked the first time that Martin and The Beatles employed reverse-played tape in one of their compositions. Martin later told the BBC that, "From that moment they wanted to do everything backwards. They wanted guitars backwards and drums backwards, and everything backwards, until it became a bore." Still, the group effectively used backwards-tape elements in some of its more painstakingly produced songs such as the dreamy guitar of “I’m Only Sleeping" or Ringo Starr's cymbals in "Strawberry Fields."

"Tomorrow Never Knows" is another great example of Martin's brew of production techniques. Thick, heavily compressed drums pump and breathe beneath distorted guitar lines; frantic tape loops rip through stereo image between Lennon's warbly, unsettling vocals, which themselves were run through a Leslie speaker cabinet (a rotary speaker usually used in concert with B3 Hammond organ) before they were recorded to tape.

Though they were not exactly the first to manipulate tape machines or to use studio equipment in unconventional ways in an effort to create the sounds they had before only dreamed of, The Beatles and Martin nonetheless brought these techniques to the forefront of popular music. In the process, they once and for all changed the relationship between the artist and the studio: it had now become a place for experimentation and composition, and the aim of recording was no longer to merely capture a performance for playback. As a result, for The Beatles and countless others who followed in their wake, the album became more than just a collection of songs; it was now the canvas for ever more ambitious and personal artistic statements, within which the quality and inventiveness of the production became a marker of artistic merit.

Delia Derbyshire and the Science of Music

Delia Derbyshire at the BBC in the mid-1960s

In 1962, four years after Daphne Oram co-founded BBC's Radiophonic Workshop, Delia Derbyshire would also join the ranks of the sound effects laboratory. Armed with a degree in both music and mathematics, Derbyshire had an uncanny ability for understanding and constructing audio, which Workshop co-founder Desmond Briscoe once put simply as, "The mathematics of sound came naturally to her." Though she was responsible for well over 200 pieces throughout her 11 years at the Radiophonic Workshop, Derbyshire's best known work for the BBC remains the 1963 score for the Dr. Who series. Originally written by Ron Grainer, Derbyshire was tasked with realizing the score, which called for sounds such as "wind," "bubbles," and "clouds." Without the synthesizers which would become available a few years later and with multi-track tape still in its infancy, Derbyshire went about creating these sounds using raw recordings of real-world sounds and simple sine and square-wave oscillators. Molding the crude material using the limited tools available at the Workshop, Derbyshire filtered, combined and recorded (to single-track tape), filtered again, re-recorded, and tweaked some more until the theme's sounds matched the otherworldly atmosphere of the sci-fi show. When she had completed the score and presented it to its original composer, Granier, he asked her, "Did I really write that?" To which Derbyshire reportedly replied, "Most of It."

While the Dr. Who theme brought both Derbyshire and the Radiophonic Workshop much acclaim, many consider her most profound accomplishments to be those she pursued outside of the normal jingle work for the BBC. Her collaborative works with the poet and dramatist Barry Bermange are of particular note. Her accompanying sound creations for Bermange's Dreams (a collage of people describing their dreams) and Amor Dei (a piece which focused on people's experiences of God and the devil) were as haunting as they were ambitious; often the results of intense, week-long sessions in which Derbyshire would manipulate raw oscillator tones, recorded sounds, and even snippets of her own voice – the resulting audio pieces were some of the most innovative and immersive sound collages of the time.

In addition, in the mid-'60s Derbyshire worked with fellow Workshop artist Brian Hodgson and composer and synthesis pioneer Peter Zinovieff as Unit Delta Plus; later Derbyshire, Hodgson, and David Vorhaus set up an independent studio where they collectively worked on an album, Electric Storm, which was released under the name White Noise in 1968 and is today considered a classic of electronic pop music. The album also is notable for its use of the first British synthesizer, the EMS Synthi VCS3.

Love Without Sound by White Noise (Delia Derbyshire, Brian Hodgson, and David Vorhaus)

In his 2001 obituary for Derbyshire, collaborator Brian Hodgson points to the visionary artist's compositions for the BBC documentary series The World About Us as a perfect summation of Derbyshire's creativity and technical abilities. In one particular episode, on the Tuareg people of the Sahara, Derbyshire used snippets of her own voice to serve as the sound of camel hooves, and "a thin, high electronic sound using virtually all the filters and oscillators in the workshop." Describing the process behind the piece herself, Derbyshire recalled "My most beautiful sound at the time was a tatty green BBC lampshade. It was the wrong colour, but it had a beautiful ringing sound to it. I hit the lampshade, recorded that, faded it up into the ringing part without the percussive start. I analysed the sound into all of its partials and frequencies, and took the 12 strongest, and reconstructed the sound on the workshop's famous 12 oscillators to give a whooshing sound. So the camels rode off into the sunset with my voice in their hooves and a green lampshade on their backs."

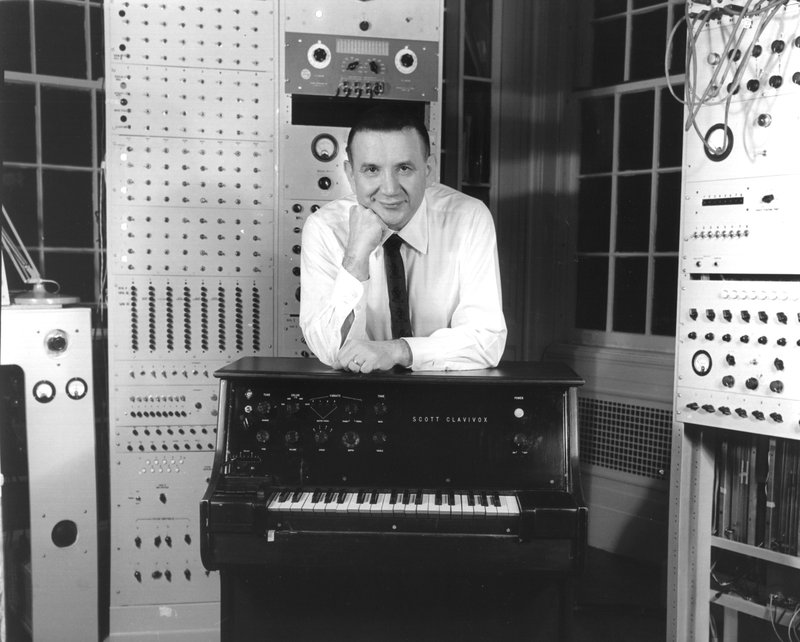

Raymond Scott and His Machines

Raymond Scott at his Manhattan Research Inc. studio in the late 1950s

Here's an unexpected fact: The man responsible for much of the music heard in the classic Looney Tunes cartoons is also credited with building the first-ever music sequencer. That man is Raymond Scott (actually Harry Warnow, "Raymond Scott" was his pseudonym).

As leader of the Raymond Scott Quintette (which actually counted six members), Scott wrote zany compositions that – though not by design – proved a natural fit for the slapstick calamities and over-the-top adventures that Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Porky Pig and co. found themselves in. Scott himself was not much of a fan of cartoons, in fact, the American musician and composer was known as an exacting bandleader who expected his musicians to memorize the music exactly as he had written, often working them for long hours and fuelling much resentment towards him. To that point, Scott dreamed of a way to make music where he was not reliant on fallible human beings to achieve his ideas. "In the music of the future, the composer will sit alone on the concert stage and merely think his idealized conception of his music," he wrote in 1949. "His brain waves will be picked up by mechanical equipment and channelled directly into the minds of his hearers, thus allowing no room for distortion of the original idea. Instead of recordings of actual music sound, recordings will carry the brain waves of the composer directly to the mind of the listener."

Scott would pursue this dream for most of his life, designing and building music machines in his own home studio, “Manhattan Research Inc”. It was here, as part of his work producing jingles for radio and television in the 1950s and 60s that Scott built what he called a "Wall of Dazzle," a 30 foot long machine with hundreds of lights and switches that allowed him to control electronically generated sounds. By today's standards he could only control the basic parameters; pitch, volume and playback speed, but for the late 1950s, this was on the leading edge of musical technology. Other custom Scott creations included the Videola (a piano that made it possible for him to play and record movie scores in real time), the Clavivox (an early version of an electronic keyboard), the Karloff, a massive sound-effects generator that was actually Scott's first electronic music creator and the Rhythm Modulator, a very basic early pattern generator.

Raymond Scott’s Electronium

Scott's most ambitious machine was the Electronium, begun in 1959, he reportedly spent close to a million dollars on improving the machine over the course of a decade (Scott later built a second version for Motown Records founder Berry Gordy). The Electronium was his attempt to build a machine which could compose and play music simultaneously; generating and performing musical ideas based on the the parameters Scott had set, making it one of the first instances in which artificial intelligence was used for musical creation.

Scott's specific musical achievements are perhaps not as well remembered as his foresight into the technological music revolution to come and the fearlessness with which he pursued ideas which must have seemed quite absurd, if not downright crazy at the time. However, it seems Scott's appropriately titled 1964 Soothing Sounds for Baby record series bucks that trend. A three-volume set intended to provide pacifying electronic sounds to comfort newborn children (at various stages of development), the unlikely series is considered one of the first longform electronic compositions intended to be used for a specific purpose and within a particular setting; in other words, it is one of the first records of electronic ambient music. Perhaps another unintended consequence of a man who dreamed bigger than most.

Read part 3 of The Studio As An Instrument, featuring King Tubby, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, Conny Plank, Patrick Cowley and others.