Sirintip: Carbon Captured in Sound

Climate change is an inescapable part of our current moment, and it’s no surprise artists are engaging with the subject on an ever-increasing scale. There are of course many ways to approach such a broad and complex topic, from conceptual studies and site-specific projects through to urgent expressions of anxiety or impassioned calls to action. For Thai-Swedish singer and producer Sirintip, the challenge she set herself on her 2022 album Carbon was to find a constructive way to communicate with people about the environment in the most sustainable way possible.

Her concern for the environment stems from her childhood memories of swimming amongst vibrant coral reefs teeming with aquatic life off the coast of Thailand. Returning to these same places in her 20s, the fish were gone and the coral was bleached, driving home the deterioration of an ecosystem in tangible, shocking terms. At the same time, she was already engaged with the idea of music with a message. When she was in high school in Sweden, she was asked to write a song for a fundraising event in response to the 2010 Haitian earthquake. After hearing the song, someone in the audience admitted to Sirintip they had switched off from what had happened in Haiti when it appeared on the television, but that the song moved them to understand the situation and do more to help.

“That was my first experience of using the power of music to make an impact and say something,” Sirintip says as she speaks from her apartment in New York. “After that, I continued to write songs about issues I cared about, but then I would run into audiences coming to me saying things like, ‘Why can't you just focus on music? Why do you need to talk about so many dark things and be so political?’”

It might be that Sirintip’s message-loaded songs were surprising to people because of the broad appeal of the music. As well as playing with Thai instruments and singing for fun when she was younger, she progressed to classical violin and piano aged 9 and then joined a choir school when she moved to Sweden before progressing to more developed jazz singing through high school. Although she never studied composition formally, by the time she was writing and performing songs in her teens she already possessed a musicality which seemed to speak to people as much as the words she was singing.

This talent didn’t go unnoticed — she was approached by EMI who suggested a deal when she was in a band in college, but turned it down when faced with leaving her bandmates behind. While she had focused on her singing and been immersed in the jazz world, a pivotal point came when she connected with Sven Johansson, a producer and sound engineer based in Stockholm who let her use his studio for a whole summer, giving her time and space to explore creative approaches to sound with outboard equipment and signal processing. It was around this time she also connected with Snarky Puppy’s Michael League, the Grammy-winning producer who signed her to his GroundUP Music label and produced and recorded her first album, 2018’s Tribus.

Johansson’s appetite for sonic exploration and League’s inventive approach to jazz and pop had a major impact on the development of Sirintip as a solo artist, occupying a space wholly distinct from her more traditional musical background. But the crux of Sirintip’s craft remains her songwriting, and her enduring concern about the environment became a focal point as she started to think towards her second album, which would become Carbon. On Tribus she had tried an abstract approach to delivering her message, conscious of her past experiences with resistant audiences, but in the end it wasn’t clear enough what she was trying to say.

“In 2019 there were big fires in the Amazon, California and Australia and with the Greta Thunberg movement and everything, climate change was just at the forefront of my mind every day,” she explains, “and I felt like I really needed to do something. I can't just do music for music’s sake, it's not me. Something clicked in my brain, and I was like, ‘what if I don't put it in the lyrics? What if I find other ways of building these concepts into the songs? What if I can find a way to make people curious?’ Not telling people what to do, but by introducing them to something they haven't heard before, that can be the gateway for them to want to learn more by themselves.”

Lockdown provided the perfect opportunity for Sirintip to begin her journey towards making Carbon, spending her days researching different topics related to climate change and thinking about ways to translate that into music. The driving motivation was to encourage conversations and let inspiration and curiosity steer her work rather than fear. Compared to her past songwriting experience which might have started with a set of chords or a lyrical theme, this time around the creative process required much more preparation before she could proceed with the actual music-making.

One significant moment in Sirintip’s initial research was discovering the MCC Carbon Clock, which tracks how much time is left until we reach the threshold of carbon dioxide emissions that will increase the average global temperature by 1.5 degrees celsius. It’s a startling deadline, but Sirintip found a way to channel this concerning data into a musical idea. Her research led her to NASA diagrams and charts tracking records of global temperatures which were also available as XML files. She imagined converting this data in musical pitches and came across the process of data sonification.

“The diagram shows how it's pretty much been the same temperature for a long time,” she explains, “and in the past few decades, it's gone up exponentially. So musically, it sounds like a note rising sharply at the end. It didn't sound inspiring to me and I didn't want to make a piece that just sounded like data, so I was thinking, ‘what if I chose years that were significant to me, or years that were significant to our shared history?’ I ended up with different, un-chronological patterns and different years because of that, and then I put them all together.”

Similarly, when she turned her attention to air pollution in Thailand it made more musical sense to focus her source data on specific parameters such as when the air pollution is worse in winter. The reliance on data to shape the musical direction of a piece meant fine tuning the ranges and rules until something satisfactory emerged from the process.

“Because it was a smaller set of data compared to the rise in global temperature I came up with my own systems,” she says, “like, ‘what if the worse the air pollution is, the more dissonant the interval is, and the better it is, the more harmonious? What if the worse the temperature is, the faster the rhythm is?’ I just made a bunch of different things and what ended up on the record is a song called ‘aqi’, which stands for Air Quality Index. I have so many more versions of that song on my computer that just sound bad, because they were different ways of translating the data that I needed to try and I had no idea how they would sound until I hit play.”

In the case of ‘1.5’ — Carbon’s instrumental track which took its cues from rising global temperatures — the initial piano piece felt out of step with the developing sound of the album. Michael League worked as a consultant (and bassist) on Carbon, and his suggestion was to apply the data sonification-sourced notes to Sirintip’s voice instead of a piano. With her choral background, singing the melodies would have been straightforward, but in pursuit of a sound which evoked the data behind the track she decided it would be more fitting to sample her voice and trigger it with the notes she had gathered.

This electronic approach to acoustic sounds also helped Sirintip express her ideas about plastic pollution. She’d already had experience of sampling traditional Thai musicians on Tribus, but for the track ‘it’s alright’ she took things one step further by seeing what kinds of sounds she could elicit from the plastic around her apartment.

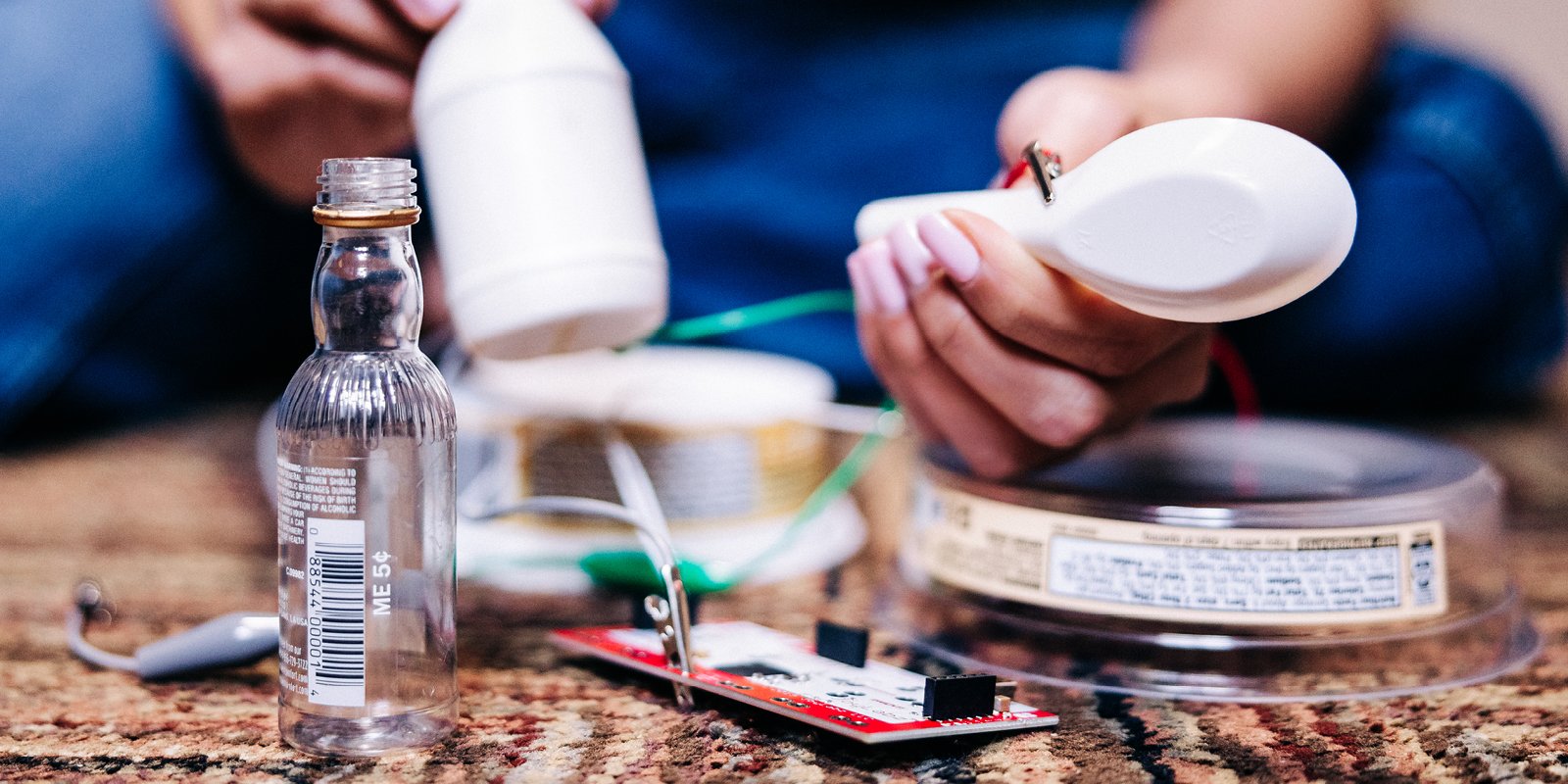

Sirintip and some of the plastic objects she used as sound sources

“I asked myself, ‘I'm writing a song about plastic pollution — how do I make that inspiring?’” she reveals. “I found it very liberating. I went into my kitchen, found some different things and sampled them on my little recorder. I got a water bottle and tried doing different things to it — filling it with water all the way, filling it halfway, stomping on it. I made a shaker by sliding a lid around on the counter, a bass sound from a bottle of spray detergent. I got so many fun sounds and loaded them into Live, and once I had a drum rack of all these sounds, in some ways it was less restricting than the process of ‘1.5’ or ‘aqi’ because I just needed to make a groove like I would with any other drum set.”

As well as building a fundamental beat for one track, Sirintip also sprinkled some of these plastic-sourced sounds elsewhere on the album. ‘Stranger of the Sea’ was initially inspired by watching a film about the nautilus — an ancient marine mollusc which has existed on earth for hundreds of millions of years. “I was so fascinated about how these creatures have lived through history for so long, like, what's their secret?”

Creating an aquatic sound world referencing the nautilus naturally led Sirintip to contemplating the persistent issue of plastic pollution in our oceans, and so it felt appropriate to use some of her found-percussion — a bottle cap doused in reverb, in this instance — to punctuate the sonic environment. “It felt very metaphorical to have the plastic water bottle being the only percussion sound in that song,” she says.

Sirintip and some of her percussion objects and contact microphones

Beyond the research which fed into the songwriting, Sirintip also applied her environmental concern to the wider process of making Carbon. This led her to discover Manifold Recording, a high-end, carbon-neutral studio built by Michael Tiemann in North Carolina, where she ended up recording her album over the course of nine days.

“It's in the middle of the woods, there's no phone service and it's 20 minutes away from the closest gas station or anything,” Sirintip explains. “It's really remote. The studio is powered by the solar farm next-door. Nic Hard, the recording engineer and co-producer for Carbon, has worked in so many studios around the world, and even he was saying it was one of the best studios he’s ever worked in. It was built to be a studio, so acoustically the space is better than when someone builds a studio inside of a building.”

When it came to manufacturing her album, Sirintip was initially considering not creating a vinyl edition given the format’s reliance on toxic processes and PVC materials. Then she heard about Evolution Music, a company in the UK pioneering bioplastic vinyl and minimising harmful processes in vinyl production. As well as being made from an industrially-compostable material, the company’s so-called Evovinyl also requires lower temperatures for pressing, making the record production process less energy intensive.

Sirintip’s US-based label, Ropedope, reached out to Evolution Music and secured Carbon’s position as one of the first LPs to complete their run on the company’s bioplastic ahead of the wider production runs beginning in earnest in Spring 2024. It’s not lost on artist or label that the records still need to be shipped from the UK back to the US before continuing their onward journey to shops and customers, but while global options for bioplastic vinyl pressing are only available at Evolution vinyl, it felt more urgent to embrace a bold new manufacturing initiative.

“It was about people being aware that bioplastic is an option,” Sirintip points out. “Oftentimes, especially in the music industry, there's so many things that are unsustainable, and no one is even asking the questions of how can we make them more sustainable?”

Sirintip isn’t under any illusions about the environmental impact of recording and manufacturing her album. She commissioned a carbon calculator to examine the emissions related to the making of Carbon, and the largest portion in fact came from the two and a half years she spent writing the record and then finalizing it in her New York apartment. What this points to is the systemic, structural issues which face humanity as a whole rather than the changes to very specific parts of any process. While she tries to make conscious decisions about her lifestyle, the reality of living in modern society brings inescapable environmental impacts that cannot be changed by individual choice alone. One area she is able to work on is her approach to touring.

“I've been trying to not do one-off shows,” she explains, “and if I'm going somewhere far, I try to be there for a longer amount of time to reduce my travel and be more effective. At this point, that's all that I can do. I've been thinking, ‘should I only do performances in VR, so I don't need to travel anywhere?’ But that is a conflict because I do also think, with everything going on in the world we need personal connection and to meet in groups, more than ever.”

Two years on from the release of Carbon, Sirintip is already working earnestly on her next project. During the previous research process, she found the two main challenges were being confronted with complex scientific information beyond her immediate understanding, and the prevalence of misinformation she would encounter. To that end, she successfully applied for an artistic residency on a research ship studying plankton in the North Pacific Ocean.

“My role on the ship was to write music based on the plankton scientist’s research,” she says, “and that interaction of experiencing science as it happens firsthand and being able to ask the scientists questions really changed everything for me.”

Following that initial trip she expanded the project to include another composer — Danny Jonokuchi — and visual designer Nitcha Tothong, working with the same scientists as well as additional mycologists studying fungi. The overarching theme sees the inter-connected, vital but invisible role of these microorganisms as a metaphor for the unseen, unheard but equally vital people which help a society function. With direct access to the science, Sirintip hopes to avoid the pitfall of repeating inaccurate facts.

“I think it's important for artists to take responsibility and try to make sure that we're not spreading misinformation,” she says. “When I was on the research vessel, there was an article that came out stating 90% of plankton were gone. It went viral, and a lot of people were sending this to me, asking, ‘is this true?’ I asked one of the scientists and they said, ‘no, they are cherry picking their facts and manipulating the data.’ The scary part was one of the outlets that shared it was a massive documentary. It’s so important for artists to make sure we're not accidentally being a part of that. When there's a politician saying something, society tends to question them. But because artists can connect to the heart, people tend to trust them more.”

At a time when the urgency of the message of climate change needs to be balanced against an audience’s receptiveness (or resistance) to the topic, artists like Sirintip are learning all the time how to better reach people with the burning issues.

“Compared to when I started 14 years ago, I feel like I’ve had more positive interactions and consequences approaching my music from this angle,” she summarizes. “I love working with experts, and I love the research. Earth is beautiful and inspiring. The more we can connect with it, understand it, the more we’ll all prioritise to take care of it. Right now, that needs to be our focus before we reach the 1.5 C scenario in just five years.”

This interview is part of a series of collaborative articles that explore the relationship between music-making and environmentalism, made together with Magnetic Magazine.

Read their version of the article

Follow Sirintip on her website, Bandcamp and Instagram

Text and interview: Oli Warwick

Photos: AgAu Photography