Sidechain Compression: Part 2 – Common and Uncommon Uses

Now that we’ve learned about sidechain compression and its origins in part 1 of this series, it’s time to get our hands dirty. In this piece, David Abravanel provides some examples of sidechaining applications in Live 10 – from recreating classic pumping house chords to head-spinning experimental trigger networks.

The almighty kick

Without question, the most popular application of sidechaining involves having other instruments fall in line behind the awesome power of the kick. In house, techno, or hip hop, sidechain can be the difference between a kick struggling to breathe in the mix and a strong, heavy thump.

It’s easy to get started sidechaining this way. First, put a Compressor device on every track that you want to duck the kick. Where you put the Compressor is up to you – traditionally it goes at the end of the effects chain, but you might find that you like the sound of, say, reverb after the ducking.

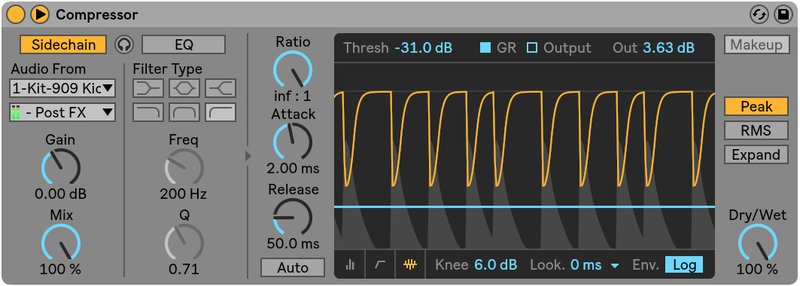

A Compressor set up for a track to duck a 909 kick drum in Live 10

Enable “sidechain” on the Compressor, then select the track that you want to use as a source signal. Note that there’s a second selection box for choosing pre-/post-FX or post-mixer – useful if, say, you’ve slapped a heavy distortion on the kick but you want the more transient original signal to be the sidechain source. If you’re using a Drum Rack as a ducking source, this second box is also where you select whether you’d like to use the entire Rack as a source or just one part.

Select ratio to taste (in the example above it’s a limiter for the heaviest effect), and play around with attack/release/knee until you’ve got just the right pump and snap. Once you’ve put a sidechain on a track, you might try increasing the output gain, for an even more dramatic “rise” at the tail end of the pump.

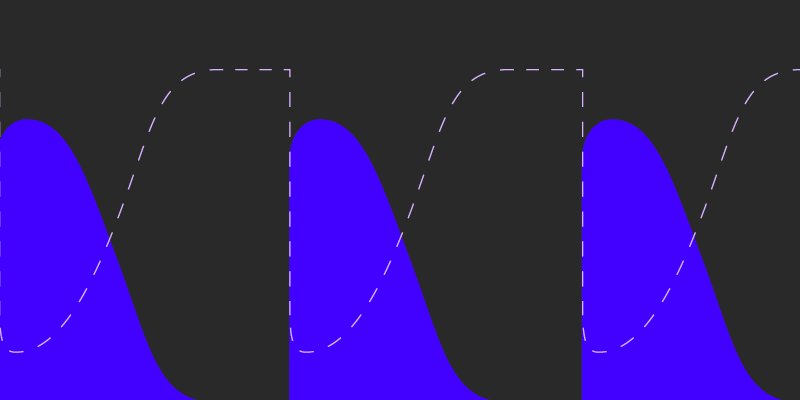

In the example above, I’ve recreated the iconic French House pump of Daft Punk’s “Indo Silver Club”, an example we heard in the last article. Note how the ducking shapes the track – and also how the kick becomes noticeably fuller partway through. In this case, I started with a high-pass filter on the kick, then removed it to bring in a heavier sound – an old trick that you’ll hear in many house and techno intro sections.

Bump it

In hip-hop, sidechaining helps to accentuate the “bump” sound that you get with a heavy kick. We’ve previously heard examples of this in tracks from J Dilla, Madlib, and Flying Lotus. Below, check out an ambient, Boards of Canada-style hip-hop beat with no sidechaining:

It’s a nice enough loop, but do the drums really grab you? Now let’s turn on sidechaining for the chords, lead, and bass:

Now there’s a serious kick. In addition to making room for the drums, sidechaining here also provides the track with a kind of bond – it feels like the whole is more than just the sum of its parts.

The long tail

In techno – especially the modern, dark variants – it’s common to hear larger-than-life noises and pads with reverb tails that stretch far out into the horizon. In this case, we’ve got a distorted 909 (using the 909 from Drum Machines and the new Pedal device in Live 10), an acid line, and a pitched-down speech sample with an enormous reverb tail. Left totally naked, these parts can make a real muddy mess:

Between the reverb cloud and the acid line, things just get murky. The drums seem to be swallowed up, and it feels like the parts are fighting with each other.

In this case, I’ve used the entire drum kit as a source for the sidechain on the other parts. The smack of the kick and snare cuts through, without sacrificing the overwhelming, claustrophobic feel that I want from the synth and reverb cloud. When you’re working with heavier tracks, you may want to duck things with more than just the kick.

Elbow room

In the last example, we heard some parts fighting each other. Truthfully, this is often easier to manage working with software instruments. Things get more difficult, however, when you bring external instruments into the mix. In the example below, I’ve got a pop rock tune – listen to what happens at around 0:20, and again at 0:40:

I like the tone that I’m getting from the chords that come in at 0:20 (again, thanks to Pedal), but they completely smother the rest of the piece. The lead guitar that comes in at 0:40 is barely audible! In this case, I don’t want as dramatic a pumping effect, but I definitely need to stop those chords from hogging so much space.

I've again used the whole kit (which here mainly means the kick and snare, as the compressor is in peak mode and those two parts "punch" the strongest). The results here are subtler – this is sidechain compression as a utility, not an effect – but no less essential. The mix still isn’t perfect (that lead is still kind of buried), but the drums have much more life and the track has a better balance. Also, I was able to beef up the bass a bit by having it sidechained by the kick, to avoid the two low-end parts fighting for space.

Beyond compression

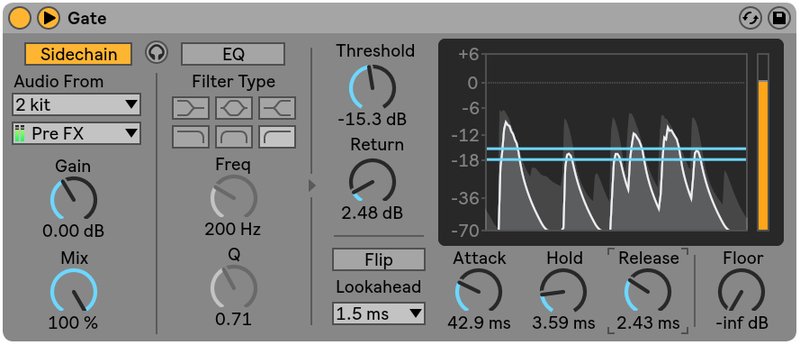

Thus far, we’ve looked only at compression. But Live includes sidechain sections in other devices, too – namely Gate, Multiband Dynamics, and Auto Filter. A brief primer on gating: it’s like a flipped limiter. Instead of making loud sounds quieter, it makes quiet sounds quieter.

Gate in Live 10, with a sidechain signal

In Live 10, the Gate device attenuates every signal below a threshold – the attenuation level is set with the “Floor” control, with “-inf DB” being a true gate (otherwise, what we have is technically an expander, but we won’t tell if you won’t). A basic way to think about sidechain gating is: the affected sound only plays with the trigger sound does.

In the example above, we’ve got a basic techno loop with a lush pad going through a delay (Echo, the new delay in Live 10). It’s nice, but it could be more animated. Now listen to what happens when we put a sidechained gate between the pad and Echo:

Instant dub techno rhythms! In this case, placement is key – gating the sound gives it a nice animation, while keeping the echo intact leaves the track feeling filled in.

It’s not hard to make anything fall in line using a sidechained gate – observe:

The track above started with random triggers of a series of jungle vocal samples. It sounded cool, but, paired with the house beat and bassline, it was just one big clash. One kick-triggered gate later, and we’ve got a hastily-assembled piece of microhouse.

It’s gonna get weird

So far, we’ve heard a number of ways in which you can use sidechaining for relatively “normal” effects and mix fixes. But like anything to do with audio, there’s a more experimental side that also deserves your attention. Going back several years, Eventide’s Omnipressor (1972) is remembered for inventing look-ahead in compression by delaying the compressed signal from the sidechain, but also introduced the thoroughly weird “dynamic reverser” mode. Inverting a compressed signal on the sidechain, it resulted in something that changes a drum kit into percussion gasping for breath. It’s one of the effects that you can hear below:

So…what’s going on here? A lot, to say the least – there are sidechains coming from tracks which have been themselves sidechained, loops of sidechaining that traverse multiple parts, sidechains on filters, compression, and gating, and who knows what those backwards sucking noises are. The point is: this was a track made to try out new sounds. There was no sound in mind – it was all about creating a kind of ecosystem of sidechaining to bring life to a set of sounds and have them play off one another.

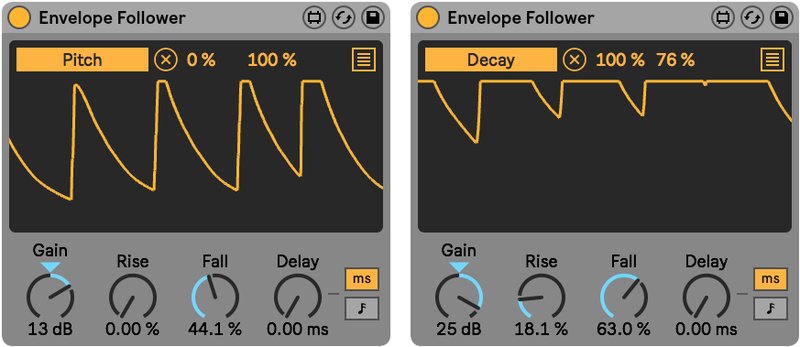

The possibilities with sidechaining are truly infinite. In the example above, two Envelope Follower Max for Live devices are used to map the signal of a kick drum to the decay of a Resonator and the pitch of a Grain Delay. There’s nothing to stop you from mapping any signal to any parameter.

Max for Live Envelope Followers in Live 10

From its humble beginnings as a fix for Hollywood sound recording to its current ubiquity across dance music and hip hop, sidechaining is quite a versatile tool.