Robert Henke: Lumière

One of the original developers of Ableton Live, internationally acclaimed artist and more recently, sound studies lecturer, Robert Henke has always operated at the intersection of art and technology. His most recent undertaking is Lumière – an ambitious audio-visual spectacle which sees Henke playing and controlling a bank of lasers in precise synchrony with his own beat-driven electronic score.

After several performances in Europe and Japan, Lumière is set to be one of the highlights of the upcoming MUTEK festival in Montreal, Canada. While there, Robert Henke will also take part in a conversation with festival founder Alain Mongeau at the Ableton Lounge. We caught up with Robert shortly after he performed Lumière as the closing concert of this year’s CTM festival in Berlin.

Excerpt from Robert Henke's Lumière

The nexus of technology and art are a constant in your work and you also have a reputation as someone who builds his own tools of artistic expression. When you started working with lasers for the Lumière project were you reminded of an earlier phase in your life when you were figuring out how synthesizers work or how to program software?

Not for Lumière, because Lumière is the second project I’ve done with lasers. The first project was an installation called Fragile Territories and when I was working on that I really started with nothing but theoretical knowledge about how it works. So my first steps in the world of laser graphics were figuring out how much of what I have theoretically in my head, works out practically. To my great satisfaction, all my initial concepts turned out to be true.

However, the discrepancies that came up at a later stage were so massive that it completely changed my idea of what I wanted to do. Because one of the things I learned – and this is, in a way, very typical of learning instruments – is that the beauty is on the edges, the beauty is when you hit certain limits, when you reach a point where the inherent behaviour of the instrument/medium/machine starts playing a role. So as long as you just play notes, like MIDI notes and it doesn’t matter how the instrument sounds, you’re not working with the instrument, you’re just working with your conceptual idea. If you try to play the piano really loud or very softly, then you actually feel the details of the instrument.

For me, the experience with working with the lasers was exactly the same: What happens if I run them at the lowest possible level of brightness before the lasers stop working? How does the colour change, how does the perception of light change if I play with them very 'quietly' in a musical sense? What happens if I drive them really hard? What happens if I turn them on and off 96,000 times a second, do I really get a sharp edge? What happens when I draw something extremely fast, do I get what I put in and if not, what do the artefacts look like? This is the point where you really start to engage with your own instrument and where I personally get the most satisfaction out of it because I feel I’m operating it in a playful way. I put something in, I get something out and I react to it.

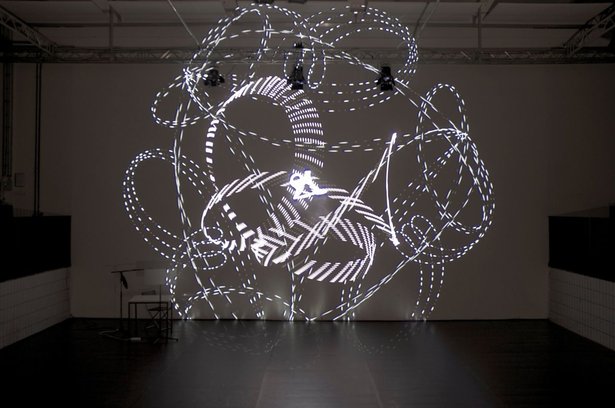

From a rehearsal for Lumière

You’ve described Lumière as an instrument, so obviously you are thinking of it as a unity of the visual and audio component as one synaesthetic instrument. That means you are playing and controlling the music and the lasers simultaneously?

The initial intention was much less straightforward. I wanted to do some beat-driven electronic music and a visual component created with lasers and I wanted to be able to control both in an improvised way. So the aspect of improvisation, both on the visual and on the sonic side was an essential part from the very beginning, but the interaction between the visual and the sonic side changed a lot.

I use the Session view in Live to drive MIDI tracks to sequence drums, but I also use a MIDI track which controls a Max for Live device that sends control data to the laser computers. Those control signals are actually analog voltages which drive the laser diodes and the movements of the mirrors. They are not meant to be audio but technically they are the same and I feed them back in my audio path to add a layer of glitchy digital noise that is in a strange and interesting way completely in sync with the visual patterns.

One of Robert's Max for Live devices for Lumière

One problem I had to solve was that the lasers are controlled by Max patches located on two separate computers close to the lasers, and the sound comes from a third laptop and the communication between those machines is ethernet via Max for Live, and there is some latency and some jitter.

I solved it by basically recreating a simplified laser control software as a Max for Live device within Live. There are now two versions of the laser generator: one is actually driving the lasers on the remote machines and one laser generator is just used for sound creation. But they’re both fed with the same control signals, which means that I send a command like 'circle' and then a few description tags like 'size 5', 'speed 7' and then a few more attributes. This is interpreted by the laser computers as shapes and at the same time within Max for Live on my audio computer as sound. And this works beautifully.

That’s quite a simple, elegant solution to the problem.

From a conceptual perspective, it is indeed a simple solution. But practically, it’s a huge piece of software, because the laser shape generators I wrote are quite non-trivial. This earned me a lot of respect from the laser company because I did certain things with their lasers that would be impossible to do with their own software.

So, if this whole music thing doesn’t work out for you, you can start working at the laser company…

I would enjoy this as a matter of fact. I have a really intense relationship with these machines and I more and more understand the technical side of all this, including the hardware. We had a failure of a scanning unit (the things that are moving the laser beams are called scanners) and I learned how to replace a scanner in such a machine, simply because it had to be done and I thought: Okay, if I’m working with this medium, I want to understand it.

I’m a very extreme case in this regard because I write my own software, I build my own hardware etc. and the opposite model, which is equally valid and has also lots of pros and cons is: you are the artistic director, you’ve entirely focused on the conceptual idea, and you have people drawing the shapes, designing the software, designing the hardware. For me this was never an option because I simply like developing software, it is part of what I feel comfortable with, but also the results I get are in many ways connected to the knowledge I gain by doing things by myself.

Robert prepares to perform Lumière

Were you also concerned with the way in which an audience that has little or no knowledge of the technical constraints and problems and solutions involved, how they would perceive Lumière?

The funny contradiction I always experience, and maybe it isn’t even a contradiction, is that nerds/technically informed observers of my work are much, much more forgiving than an uninformed audience. Because the nerds always share the childlike experience of “oh wow, fast-moving laser beams! Wow, he creates white out of blue and yellow, that’s tricky! What kind of driver software do you use?”

But if people have no clue about the complexity, even if people don’t have a clue about the comparable art or music or audio-visual things… the more uninformed people are, in my experience, the more precisely they find the weak spots. They say things like: “That last part was too long” or “I didn’t understand why you had to put in this shape while you’re doing that shape” or “it was just too much at some point” or “I liked the quiet parts more, why didn’t you make them longer?”

The question for me is: what do I want to show people? What is the thing I want to expose? Is it a showcase of technical excellence? Is it a novelty show or is it something which operates on a different level?

So, what is the answer?

Of course the latter, because I strongly believe that… well it sounds a bit strange but I’m not looking for the short-term excitement of “the new”. The music or the movies or whatever artistic expression I like most are things that have a certain timeless component to them. Timelessness is the opposite of being on top of technological development. Whilst I enjoy the technological side and whilst it’s really great that I can work with these lasers which are much, much more precise than what was available a few years ago, whilst I’m benefiting extremely from advances in technology, I still want to do work which if you watch and listen to it in 20 years, still stands up. This is something that must be fed from a different source than the megahertz, milliseconds or other parameters. There must be something that transcends resolution.

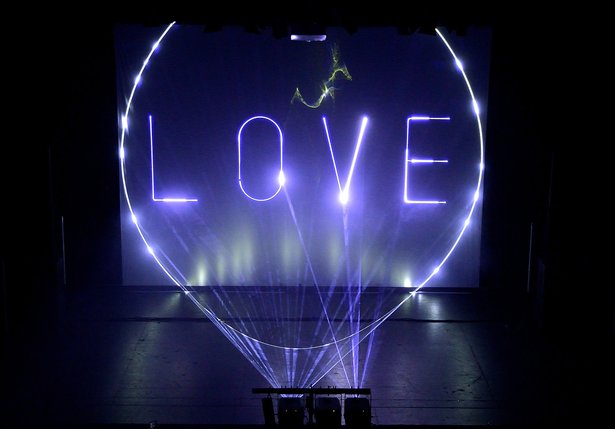

"Love" from Lumière

And within Lumière there is something like a progression of forms: the first part features abstract shapes and lines and then at some point numbers are introduced and eventually there is text. It’s two words and…

... it’s the two words “Love” and “Code” and it is of course a reference to all the other artworks that deal with the graphic nature of the word “Love”. Adding the word "Code" just happened and I liked it. Despite all the abstractness and the mathematical aspects of the word and its connotations of accuracy and technology, what finally drives me, is of course deeply emotional. For me, love is a perfect symbol of all this, it’s about being emotional, doing something not because there is a necessity, but because I love to do it, and my relationship to code is also driven by the desire to create something that touches people. So “Love/Code” for me is a strong combination.

Each word is both a noun and verb.

Yeah, I didn’t notice but you’re right! Interesting, cool. So it was a mix of playing with the meaning, also embracing the audience in that way, because I end the piece with “Love”: forget about the abstract part, let’s remind ourselves of why we are here in the first place, because we want to experience something beautiful.

And the section of Lumière with all the numbers: those are all the unlock codes ever generated for Ableton Live, is that correct?

[Laughs] No, but I like the idea! I never thought of it like that. That would of course be fun to transmit a lot of hidden information which would be only helpful if someone knew what it means. It would of course be a nice internet meme, that one of those numbers could unlock your Live forever. A golden ticket for a lifetime license of Live… Well, it’s actually random digits, as a matter of fact. So who knows, one of them might work!

Find out more about Robert Henke and Lumière