Nosaj Thing: A Visual and Musical History

When the beat scene first percolated from the Los Angeles underground, it was decidedly all about the music. A diverse array of talent, from early key figures like Daddy Kev and Ras G to high profile artists like Flying Lotus, Daedalus, and others practically pre-ordained that the music would be full of cross-pollinated recombinations. Hip hop, jazz, electronic and any other number of genres and styles emanated from DJ decks and laptops alike. Visuals weren’t on any musician’s radar. Yet.

This began to change when the beat scene found international acclaim around 2009. Since then, many of the artists associated with the LA scene have built strong visual identities. FlyLo is known for cinematic music videos, which he often directs himself, and has explored holographic 3D live visuals. The Glitch Mob, of course, have their futuristic, multimedia stage environment “The Blade,” while Daedalus has practically cornered the market on performing in sartorial dandy fashion.

Fog – a track from Nosaj Thing’s debut album “Drift”

As far back as his 2009 debut LP Drift, Beat producer Nosaj Thing (aka, Jason Chung) knew he wanted dynamic visuals for his live music. Chung tells Ableton that while he grew up DJing, following the DJ battles held by Disco Mix Club (DMC) and The International Turntablist Federation (ITF), he’d originally planned to be a graphic designer. So it was only natural that he would drift into the borderlands where sound meets vision.

“[My whole career] has been a research and study of how to make an electronic music project a live experience with visuals,” says Chung. “A lot of people can relate to this. A lot of up-and-coming producers who want to perform and have visuals don’t know where to start. It’s a way of thinking: do you want visuals, or do you want to create a whole new world? You can work with different mediums, light, projections, objects, scents.”

“The most important thing is the concept and the direction instead of just making something look interesting.”

Drift: A Visual Genesis

After Chung released Drift, he and fellow beat scene artists quickly realized people were taking notice. And it wasn’t just regional and national interest. Venues in countries across the globe wanted Nosaj Thing, Flying Lotus, and others to play shows to fans clamoring for their music in a live setting.

Chung, who had just toured with and remixed The xx, felt it was time to do his own show. Wanting to enhance the live Nosaj Thing experience with visuals, he researched light installations and video projections by other musicians and artists. Chung looked to these and YouTube videos to take his first steps into live visual research.

“At the same time I started doing this research, my roommate at the time, Adam Guzman, was studying media deign and he just wanted to get involved and help me develop it,” says Chung. “I think the first time we performed it might have been at this movie theater called The Independent in downtown LA [in 2009], and it was kind of a one-off night that Brainfeeder put together. I performed in front of the movie theater’s screen kind of in silhouette like the beginning of Disney’s Fantasia.”

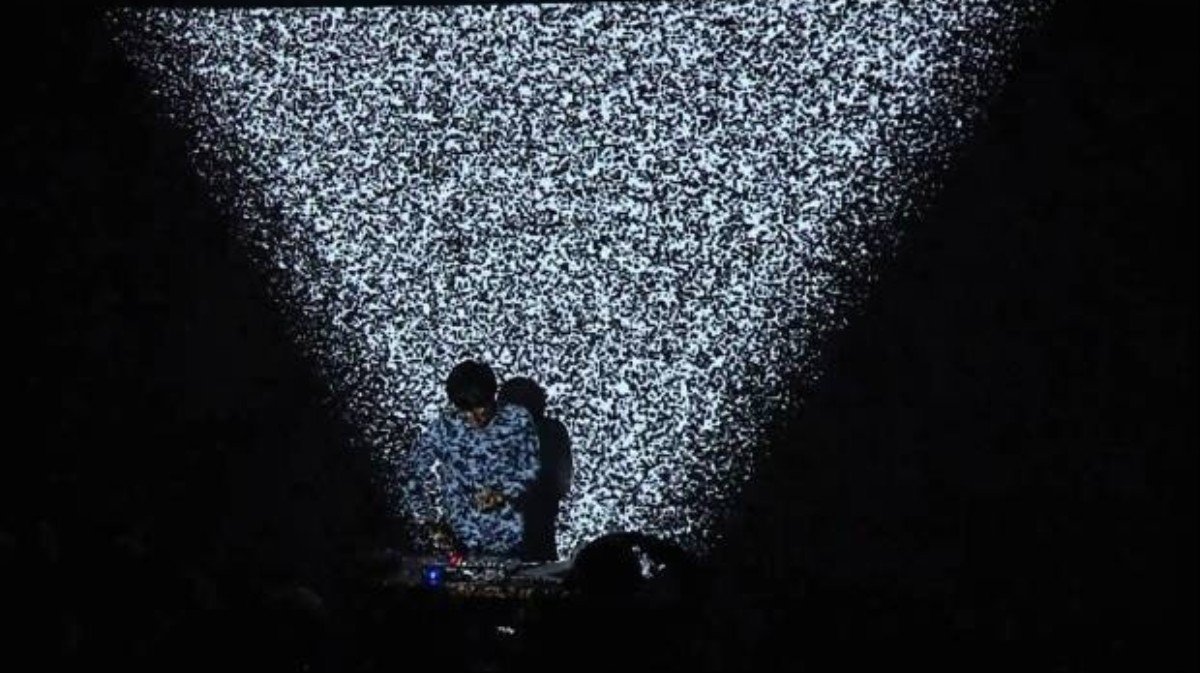

Nosaj Thing performing in LA in 2009

“Something about that visual struck me because performing as a bedroom producer, we’re not really used to being in the spotlight, and we're not like playing guitar or singing or anything,” he adds. “But then I still found that the body movements and something about the silhouette were really interesting and powerful.”

Taking inspiration from Fantasia, Chung and Guzman conceived of projected animated visuals that would be a study in color. For each song, they chose a color with simple animations to bring the performance to life. As Chung recalls, Guzman triggered the clips with Modul8 software.

“Another reference that we kept on watching was the film Stop Making Sense by the Talking Heads, which was more like performance art.” says Chung. In that film’s intro, David Byrne famously walks on stage, hits play on a cassette deck that triggers the “Psycho Killer” beat, then proceeds to play along to it with an acoustic guitar.

“Adam already knew about all this stuff,” says Chung. “He studied graphic design and media design. In that way, it was a great collaboration because I had originally wanted to go to school for graphic design and I chose music instead. So, it meant a lot to me to bring back this interest with my performances.”

Alternate Realities with Daito Manabe

After the Drift tour, Chung entered the next phase of his career—a highly productive and equally experimental time. Musically, he shifted gears to production work for hip hop stars Kid Cudi, Kendrick Lamar, and Chance the Rapper, amongst others. And, once again, the collaborative impulse extended to visual realms.

In 2012, while doing live visual research for Home (2013), Chung’s follow-up to Drift, he came across the work of Japanese artist Daito Manabe. A programmer, interaction designer, and VJ, Manabe had recently garnered critical and social media attention for Electric Stimulus to Face, a performance that used sound to generate facial expressions. Manabe did this by attaching myoelectric sensors to face muscles, which then twitched according to specific tonal outputs. Manabe uploaded several of these tests to his YouTube channel, which is where Chung originally came across his work.

“I was like, oh, this is so crazy… I just need to contact this guy,” says Chung. “At that time, Twitter was hella new—it was like 2010 or 11 or whatever, so I found him on there and sent him a little message on DM.”

Manabe quickly replied, saying that he knew Nosaj Thing and had been following the wider LA Beat scene. Chung soon discovered that Manabe was a like-minded music head, proud owner of doubles of every J Dilla record, and even knew how to scratch. The two agreed to collaborate on what would become an ongoing creative partnership.

“I’d never gone online to work with someone before, so I just sent him some stuff that I was working on, and somehow he was just like, yo, let's make a music video,” says Chung. The track that served as the foundation for the pair’s collaborative video was “Eclipse/Blue,” a track from Nosaj Thing’s 2013 album Home, which featured the vocals of Kazu Makino from Blonde Redhead.

“Vice’s Creators Project, who already had a relationship with Daito, said they could help make the video happen,” Chung says. “And it made the rounds after it came out because it was a really new experimental technology that Daito was working on.”

To make the video, Daito’s team tracked the choreographed movements of two dancers – one in front of a screen, the other behind it. Then, in real time, Daito’s programmed animations were projected onto the dancers’ bodies. The result is a mesmerizing and psychedelic fusion of bodily and computer-animated movement.

After the success of Eclipse/Blue, Chung and Manabe realized they could actually perform with this technology. They wanted to tour it, but budget and logistics (it would require a full team) presented immediate challenges. A live iteration would have to wait.

Following the release of Nosaj Thing’s 2013 album, Home, Chung did various visual experimentations for live shows. One particular idea he explored was rear projecting light onto fog drifting through three-dimensional space. In that way, the visual schema mirrored Home’s sonic palette—landscapes of light matched by the album’s deep layers of ambience, punctured by minimalistic beat programming. Just as often, live shows on the Home tour might not have any visuals at all, apart from basic lighting.

Image from a Home-era Nosaj Thing performance

“It was a time for me to just focus on improving the music side of the live set,” says Chung. “I didn’t have many resources and budget to do the shows I had in my head.”

Nosaj Thing’s lo-fi DIY approach to live visuals continued with the release of his 2015 record, Fated. While doing a run of shows, misfortune struck: thieves broke into Chung’s tour van and stole everything, including the hard drives containing the stems of his next project—the No Reality EP, which would coincide with a tour with Manabe.

“It was just such a shock because that was the first time where I lost all of my work because I had all of my hard drives with me,” says Chung. “My backups were stolen too, so it was a really hard pill to swallow. The only thing I could do is really see it as an opportunity to reset, refine, and make better work.”

After remaking the No Reality EP from the ground up, Chung and Manabe finally got the accompanying No Reality tour off the ground. Conceptually, it was an evolution of the Eclipse/Blue audiovisual blueprint. Debuting at the Taico Club Festival in Japan, as part of a music festival, it consisted of three X-Box Kinect cameras that triangulated the duo’s audiovisual setup, as well as live video shot by a person moving around the stage. This visual stew created a parallel between the real figures of Chung and Manabe and the unreal—their virtual avatars, warped with the programmed visuals in real time.

A brief look at Nosaj Thing and Daito Manabe's No Reality

“It’s called No Reality because on stage you're able to see everything that’s happening live with us right in front of you, but also an alternate reality through the camera screens,” Chung explains. “That was all happening live in parallel, so it was like being able to generate a parallel reality live, where you’re able to change the camera’s perspective like in a video game.”

“Everything was happening in perfect sync,” says Chung. “Daito had all the MIDI information and audio information feeding out from my laptop into his system and the 3D rendering and processing were happening live. I was also wearing a motion capture suit that was connected to his system too, and there was a camera on my head to switch from first person to third person—it was really fucking cool.”

Chung and Manabe toured No Reality hard for several years, bringing it to Coachella as well as several Sónar festivals. But, as one might expect from the pair, it was an ever-evolving audiovisual affair. Over time, Manabe made the setup more lean and efficient, with more advanced 3D capture technology.

“Visually, I got more involved with the way it looked,” says Chung. “I flew out to Japan and we just really refined it. I got more involved in the color palettes and in reviewing every clip, whereas at first Daito was just doing everything with this team.”

Light and Fog

When Chung was in Japan debuting No Reality at Taico Club Festival, he had the pleasure of seeing Autechre perform. Seeing the iconic electronic duo is a bit of a misnomer, though. Over the years, Sean Booth and Rob Brown have become known for performing in absolute pitch black rooms. The idea being that the darkness is the void or canvas upon which their sounds build a sort of three-dimensional quality for the audience.

“That Autechre show definitely inspired me,” Chung recalls. “What I really loved about it is that it reminded me that there are no rules to this. And it's more about creating the experience that you want your audience to hear and see. I feel like for Autechre it makes total sense because a lot of their music has so much detail and intricate programming.”

“I also saw Dean Blunt perform as Babyfather, and he filled the entire room with fog and just lit the entire space with really bright white flood lights so that it was super bright,” Chung says. “You couldn't see anything. I couldn't even see my hand in front of my face, it was crazy. It was the opposite of Autechre and it gave me a totally different feeling: I felt like I was in the afterlife or something.”

So when it came time to perform live in support of his 2017 album Parallels, Chung had his concept: it would be about space and light. He wanted to return to the atmospheric palette of light and fog he’d used for some of the live shows he played in support of Home.

For this tour, he wanted to perform this one on his own. To do this, Chung enlisted the help of a lighting designer friend Matt TK. Using MIDI, he was able to control the powerful Clubman 3000 laser and a strobe light to fashion mesmerizing textural and optical effects on the fog drifting through the room.

Nosaj Thing performing with his strobe and laser trio.

“I was able to trigger these elements with Ableton,” says Chung. “I drew MIDI clips kind of like how you program drums. I also imagined performing as a band, so I was stage left, the strobe light was in the middle on a 10-foot stand, and the laser was on the right. The strobe was kind of like the singer, which was programmed with the main phrases of the song, while the laser set each atmosphere, filling the entire space of the venue.”

“I was trying to slow down the movements of the laser too because I’ve never really seen lasers programmed like that,” he adds. “I was trying to really explore and push that as far as possible. I’d love to take it to the next step and have more lasers involved, and maybe even use mirrors.”

A Study of Surveillance

After Chung took light and fog to the limits of his current setup, he switched visual gears yet again. Much like his introduction to Manabe, his next visual collaboration would begin online when Ben Wegscheider, the man behind the boutique design studio Bureau Cool, reached out via email.

“I’d never heard of Bureau Cool,” Chung recalls. “The email’s subject said something like ‘your website could be better’ or something. [Laughs] And the email contained a link to his website and I’d never seen anything like it.”

“We met in Germany that summer [2016] and just hit it off like we were already friends,” says Chung. “He's a programmer that grew up skating but he's also a graffiti artist. We just started talking about ideas and he did the web experiences for my last few releases.”

Nosaj Thing performing live with Bureau Cool handling visuals

To create these interactive web experiences, Wegscheider used a browser-based toolkit that allowed users to play with the style, motion, and type of the No Reality EP in real time. The two collaborated again for an animated website linked to Nosaj Thing’s Parallels tour website. By scrolling around the website, visitors could set the static album art in motion and manipulate it. After these early visual collaborations, Chung and Wegscheider began developing ideas for Nosaj Thing live shows.

“I’d gone so hi-fi and clean for a while that we wanted to see what we could do with just kind of lo-fi and cheap equipment,” says Chung. To that end, Chung and Wegscheider obtained several cheap, wi-fi-enabled night vision security cameras to give the visuals a “CCTV look.” For each live show, they wanted to explore the space, so they played a lot with camera placement, which changed at each venue.

“With Daito, it made sense for us to be front and center, but this time around it was more of a study of surveillance, so it didn’t make sense for Ben and I to be in the center,” Chung says. “Instead, we were on the far ends of the stage facing each other so that you could still see our silhouettes but in profile.”

“We actually didn't perform it enough to fully realize it,” Chung says. “I just also feel like every show that I've done has been an ongoing experimentation, so I feel like that's why none of it was really properly documented. It’s still an ongoing experiment.”

Back to the Beginning

By the end of the Parallels tour, Chung had been touring for most of the last 10 years. In retrospect, he realizes it was a many-splendored blessing. He got to see much of the world and connect with audiences along the way, but also watch many of his favorite artists perform. But for Chung, this life was a double-edged sword.

“That energy is something I’ll take with me the rest of my life, and it will inspire me for sure,” says Chung. “But I didn't really get to focus and really think about what I was doing.”

The Covid-19 pandemic changed all of this for Chung. Suddenly he had all the time in the world. It was a feeling he hadn’t had since his days spent recording his debut LP Drift.

“It’s a feeling that I’m going to take with me from now on—that quiet, that pause that greatly affected the way I work,” says Chung. “Before, I always felt the pressure of being rushed. While you’re working on the record, it was always like, ‘hey, we’ve got to schedule the tour already,’ and that’s not healthy for creativity.”

“Also, I was touring so much that my music was changing to the context of the energy of a live show,” Chung says. “Instead of making downtempo beats or happier tracks, which I was still making, I wanted to make tracks with more energy for the dancefloor. Now I’m making the album that I've always wanted to make. It's more of a continuation of my first record but evolved.”

Chung also hopes the pandemic downtime will help him refocus on one of his other original ambitions: producing tracks for other artists. For him, this new album is a bridge to that type of work.

“When I first started making beats I was in high school, and that's what I wanted to do,” says Chung. “I wanted to be like Neptunes, Timbaland or Dre. I always wanted to be in that producing lane. Now I want to produce the way Ryuichi Sakamato [Yellow Magic Orchestra] or Brian Eno have done it over the years. Maybe it’s just the age I’m at right now.”

This isn’t to say that Chung won’t tour. He will. But when Chung starts playing live again, he wants to be sure he does it the right way. And the right way is still an open question. All he knows is that the entire live performance will be more considered and, ideally, never rushed.

“Festivals are starting to pop back up and I definitely want to see how the next show will evolve but I'm not in a rush,” Chung says. “There's a sense of like, oh, we’ve got to get back to doing this, and maybe instead of taking all this time to think about how it might unfold, they're just sort of rushing headlong into it.”

“I think a more measured approach where you're sort of giving it some extra thought is a good thing. Now... now's a great time to take that time.”

Keep up with Nosaj Thing on his website, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and Soundcloud

Text and interview: DJ Pangburn