Matmos Present More Sounds from the Polish Radio Experimental Studio

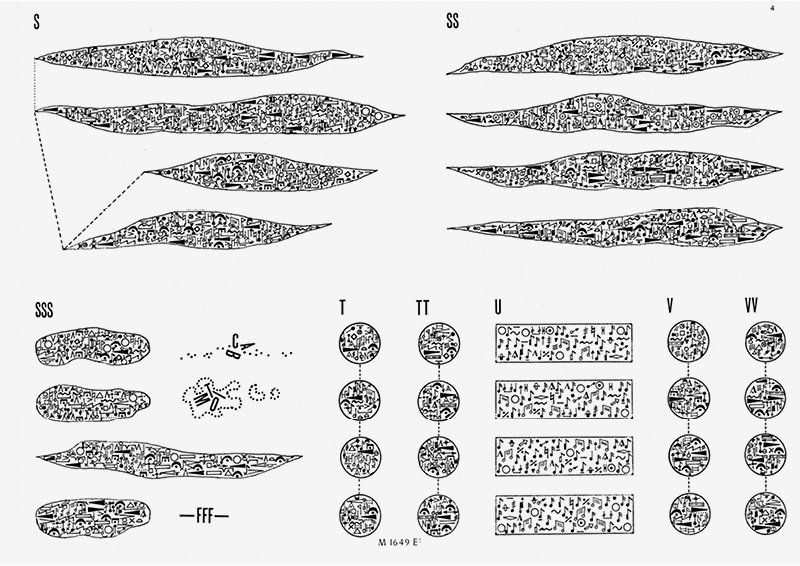

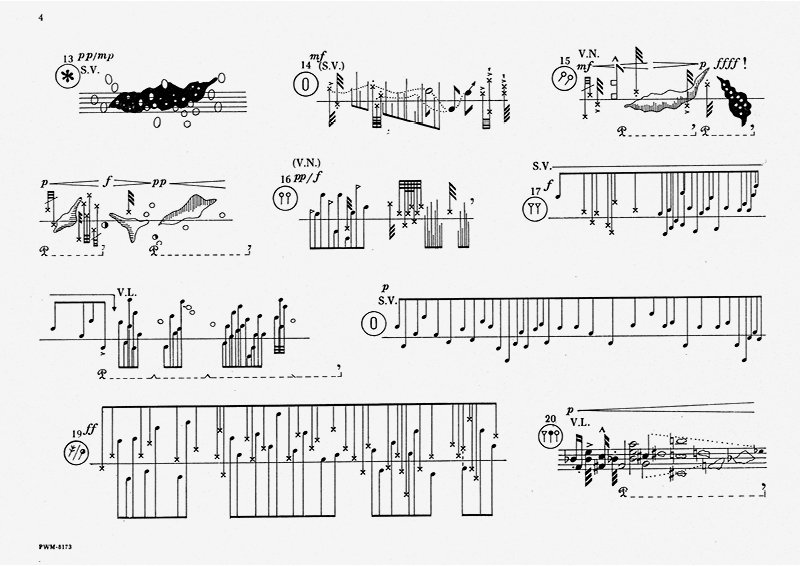

An example of Bogusław Schaeffer’s experimental notation. Bogusław Schaeffer / Copyright: Aurea Porta

The Polish Radio Experimental Studio is not a household name in the history of electronic music, but its legacy is rich with 20th Century musical innovation. This overlooked but important European musical institution was the subject of a unique sample pack pulled together in 2018 to help bring a new life to sounds created in a specific way in a specific moment in time. You can learn more about the history of PRES and access the original sample pack here. Now, we’re returning once more to Warsaw in the 1960s and 70s to explore the visionary palette of a composer as overlooked as the studio he did some of his most important work in.

Of the artists, scientists and experimenters attached to PRES, Bogusław Schaeffer is one of the most significant. A prolific, polymath composer who straddled classical tradition and avant-garde experimentation in parallel, Schaeffer did some of his most groundbreaking work at PRES during the 1970s before moving on to other studios due to the old-world analogue limitations of the equipment. In the legacy of Polish classical and experimental music, Schaeffer is eclipsed by the more notorious and name-checked Krzysztof Penderecki and Henryk Górecki. Michal Mendyk from Adam Mickiewicz Institute, who has helped co-ordinate the access to the PRES archives, suggests part of the challenge facing Schaeffer’s legacy is rooted in his attitude towards creativity.

“[Schaeffer] was, on one hand, as productive and systematic as Stockhausen,” explains Mendyk. “Technically, he produced between 400 up to 800 works. He just wrote down every idea he had. On the other hand, he was very experimental, open for improvisation and chance actions.”

Download includes a folder of audio WAV files and an Ableton Live Project. Please note: Live 10 Suite is required to make full use of the devices included in the Live Project

The sample pack is based exclusively on recordings of Bogusław Schaeffer's electroacoustic pieces created at the Polish Radio Experimental Studio

Adam Mickiewicz Institute gives general authorization to anyone who would like to use the samples in any manner, including their unlimited processing or adaptation

With access granted to Schaeffer’s archive of sounds recorded at PRES, who better to extract a sample pack from such a voluminous and idiosyncratic body of work than Matmos? Drew Daniel and Martin Schmidt have spent more than 20 years charting an imperial course through concepts and sonic processes with surgical fervour, no more so than on 2001’s A Chance to Cut Is a Chance to Cure, on which they crafted a full album of material out of samples of medical procedures. Surprising at every turn, prolific and arguably polymaths with their sidelines in performance art and higher education, Matmos are the perfect explorers for Schaeffer’s seemingly impenetrable oeuvre.

“Any time we hear about work that combines electronics and [musique] concréte and acoustic instruments, for us that's often a touchstone,” says Daniel. “Compositions from that period with that technique, that are very labor intensive; they're often highly wrought, highly abstract, and they have an otherworldly sonic quality to them because of the combination of how they were made, and when they were made.”

“I have the tendency to try to reverse engineer technique from listening,” admits Schmidt. “We’ve spent time at the GRM poking around in their basement where they keep the old gear. There was an old vocoder, an EMS, I think, that was this monstrous, desk-sized machine. And it gave me this very real experience of old tech, and what people had to go through to get the sounds they got. Listening to [Schaeffer’s] stuff I go, ‘Okay, so it's backwards speech going into a pulsing reverb with, maybe, a vocoder, or is it just filtering?’ for every sound. Those recordings are this amazing tour of techniques.”

Schaeffer’s relationship with PRES began in the 1960s. At that time, the radio station was the only place in Soviet-controlled Poland where you could efficiently produce electronic music. Even artists from further afield, such as Norwegian composer Arne Nordheim, travelled behind the iron curtain to Warsaw in order to work at PRES. Schaeffer was one of the most productive composers to work at PRES through the 60s and 70s, but as his career developed alongside the technology, he found himself travelling internationally and spending less time in Poland.

“As he started to travel a lot around Europe, [Schaeffer] started to create works in different parts using different equipment,” explains Mendyk. “For example, in Belgrade Radio there was a unique EMS Synthi 100 synthesizer which could produce sounds he couldn't in Warsaw. So, he had to travel there, record sounds and come back to make a mix here. But also Schaeffer developed technologically. He went into computer music, algorithmic music, which Polish Radio Experimental Studio never did. So in a way he went farther in this linear development and they stayed old school. He and PRES went in different directions around the late 70s.”

An excerpt of Bogusław Schaeffer’s “Monodram” – produced in 1968 at the PRES

Schaeffer’s musical legacy is many-sided. Even during his peak period of work at PRES, there was never one particular area he focused his creative energy in. From musique concréte made with his own custom instruments to electronic symphonies for performers to apply their own sounds to, electronic mass and a remarkably prescient jazz-sampling piece called ‘Blues’, he displayed a restless curiosity about sonic experimentation.

“That's a cool thing about [Schaeffer],” says Mendyk. “There was no style. Every piece was a separate world. Young artists were in a very good position in Poland in the 60s and 70s. The arts were strongly supported by the communist regime as a kind of propaganda, so he had time and possibilities to spend two months in the studio doing a six-minute piece.”

As well as the curious qualities of the sounds he worked with, Schaeffer could also embrace themes and concepts in his compositions – something which naturally appealed to Matmos when it came to searching for sampling material.

“The poetics of Bogusław Schaeffer's pieces seem to go even farther back [than the archaic technology],” says Daniel. “The piece I immediately liked the most was called ‘Heraclitiana’, which seems to be an attempt to evoke the philosophical world of [Ancient Greek philosopher] Heraclitus, who's famous for saying that existence itself is fire, and that you can never step in the same river twice. It's a vision of history as endless change. It was really cool to hear someone try to make a really open-ended philosophical statement into a specific piece of music. ‘Heraclitiana’ is full of absolutely insane, punctual, violent sonic events – lots of percussive strikes and strange combinations. There's a lot of ringing from high triangles attached to different percussive attacks. So that was the most fun immediately to start sampling because it's so internally different. I feel like we could have just made 200 samples of ‘Heraclitiana’.”

This is the first time Matmos have put together a sample pack. It’s a natural extension of their own craft, which has often taken an experimental attitude towards sample-based composition and production. Given their respect for Schaeffer’s music and the techniques behind it, the divisive specter of sample culture is detectable behind the work Daniel and Schmidt have carried out.

“I certainly hope people give a listen to [Schaeffer’s] work the way it was meant to be heard before opening this box of bone fragments,” says Schmidt. “What we've done is a sort of convenience.”

“Like when mom cuts the crust off your sandwich,” adds Daniel. “I would like us to be ambassadors here, rather than to have it be this sort of sonic MSG powder that makes your music sound, “weird”. I think part of what's sad about sample packs is if they are used as a sort of substitute for the process of finding one's own sounds.”

“What I think is valid is that this returns people to a moment when different microphones, preamps and studio rooms and a different approach to composition created textures that can never be repeated. It's a weird form of cultural memory to put these samples and sounds into the bloodstream, and to let people change them. I think that's positive. I'd like to think that Bogusław Schaeffer could be this ghost who starts to show up more because of these 200 samples.”

Daniel nods to the fact he and Schmidt sampled ‘Artikulation’ by Ligeti on the first Matmos album, re-contextualizing the Hungarian composer’s late 50s electronic experiment amongst the tropes of 90s drum & bass.

“It's about the choices creative people make with these components,” he argues. “We loved what Ligeti got out of that moment in technology. It has a very particular historic moment imprinted into it. When you sample from an earlier era, you're still doing it with where you are in time in mind.”

Even with their considered approach to the ethics of sampling, the process of dissecting Schaeffer’s work was not entirely straightforward, given its experimental and often tonally complex nature.

“The metaphor that always comes to mind is like trying to cut wet Kleenex,” says Schmidt. “It falls apart as soon as you start cutting it, and you're like, ‘Oh, no, I should have cut a little further in!’ Like, where does this sound start? Where should it end? There's a weird thing with samples, where it tries to reduce the entire universe to drums. It feels dirty to reduce someone's composition to drum kits…”

“Or stabs…” continues Daniel. “That's why we had categories like Noise and Texture, where there would be longer samples. A vocal sample that's just one singer singing the note C is the most useful sample in the world, because the creator can stack whatever chord they want. But this is not a sample of choir. This is a sample of Bogusław Schaeffer's choral music, which means it needs to take pictures of the kinds of chords or clouds of information that he created. That means it's going to be less flexible for the end user because it has a lot of his personality in it. That's a weird trade off when you're making samples, but we wanted the samples to retain as much of Bogusław's aesthetic as we could, given the weird, brief snippet framework of sample kits.”

Examples of Schaeffer’s graphic score notation. Bogusław Schaeffer / Copyright: Aurea Porta

It’s easy to imagine a self-serious tone around pioneering neo-classical and electro-acoustic music and its attendant sampled material, but both Schaeffer and Matmos preserve a sense of humour within their work. The restlessly prolific Schaeffer was as happy scriptwriting comedies as he was creating forbidding electronic pieces. It’s no surprise to hear slithers of mischievous sound tucked away in the sample pack.

“You can hear a section where this woman is laughing over and over,” says Schmidt, “and it's this very theatrical, ‘mwahaha, ahahaha, ahahaha!’ Listening to recordings of people laughing on purpose, that is just funny shit.”

Another particular sound that stands out in the sample pack is the ‘Honk’, which sounds as though it punctuates a slapstick gag at the expense of a hapless clown.

“We're making a record out of Bogusław Schaeffer and so far, we've literally only used the sample pack,” reveals Schmidt. “Like, ‘Okay motherfuckers, you chose these samples, now go ahead and make a bunch of music with the samples you made.’”

“And that one honk you're talking about is the core riff of a song we're working on whose working title is, I believe, ‘Snort Trot’,” adds Daniel.

The first results of Matmos’ work with the Bogusław Schaeffer sample pack

When we speak, Matmos are midway through the process of making the Schaeffer-sourced album, as designated by the chart on their wall. The album will no doubt be a self-contained musical universe much like the rest of the Matmos discography, and Schaeffer’s own tangled body of work. Now, the intrigue lies in what other unexpected results might arise from Schaeffer’s sounds being shared with the modern music-making community. That part is up to you.

Text and interviews: Oli Warwick

Watch an exploration video of the sample pack by Andri Søren

Download includes a folder of audio WAV files and an Ableton Live Project. Please note: Live 10 Suite is required to make full use of the devices included in the Live Project

The sample pack is based exclusively on recordings of Bogusław Schaeffer's electroacoustic pieces created at the Polish Radio Experimental Studio

Adam Mickiewicz Institute gives general authorization to anyone who would like to use the samples in any manner, including their unlimited processing or adaptation

The project is organised by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute as part of the international cultural programme accompanying the centenary of Poland regaining independence. Co-financed by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage of the Republic of Poland as part of the multi-annual programme NIEPODLEGŁA 2017–2022

Special thanks to the Aurea Porta Foundation for permission to use original Bogusław Schaeffer works