Los Guaqueros: 100 Years of Sampling

In a previous edition of our Sounds in Context series we met The Meridian Brothers, a project that combines tradition and modernity in the fertile underground music scene of Bogotá, Colombia. Active within the same network of artists, producers, DJs, and diggers are Mario Galeano Toro and Mateo Rivano, both of whom have been active uncovering dusty vinyl gems and Colombia’s forgotten musical roots and reintroducing their rhythms and styles into the country's contemporary music scene.

The dizzying array of projects Mario Galeano Toro and Mateo Rivano are involved in, together and solo, includes the jazzy Caribbean-Afrobeat mélange of Ondatropica:

Frente Cumbiero’s electronically augmented vinyl archaeology:

And even the angular surf punk of Los Pirañas:

Most recently, working together as Los Guaqueros (literally, “The Looters”), Galeano Toro and Rivano were commissioned to present a new project for the Pop 16 festival – a celebration of 100 years of recorded sound, and the birth of popular culture. But how does one condense that much musical history and evolution into a single work? The format Los Guaqueros settled on was a hallucinatory audio-visual representation of the development of different styles and traits within Colombian music, framed by the social and political context of the early 1900s.

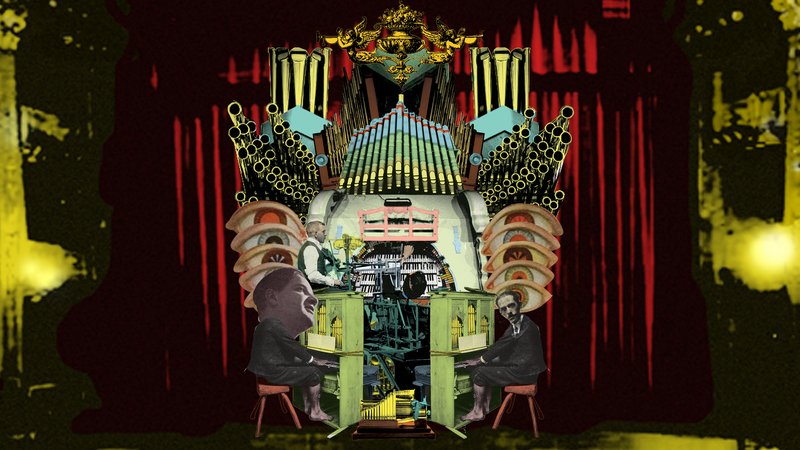

The 45 minute piece called “La Tragedia Rustica” combines samples of various early recordings from Bogotá, alongside ethnomusicological field recordings, all woven together in real time in Ableton Live and accompanied by an animated sequence, manipulated live by Rivano (himself a celebrated street artist in Colombia). A bewildering, kaleidoscopic collage of sounds, photographs, film, and animated graphics that range from Monty Pythonesque playfulness to stark archival imagery, Los Guaqueros’ “La Tragedia Rustica” is a highly artistic investigation into Colombia's musical history.

The trailer for “La Tragedia Rustica”

100 years is quite a long span of time to cover. What approaches did you consider for this project?

Mario: Both Mateo and I have been digging for records for many years, but records from 100 years ago are super hard to find, so we had to start really researching and investigating when things were recorded, who was recording them and so on – trying to uncover some examples of the music that we could put in the piece. When you go look for a sample in the national libraries it’s not well catalogued and it’s hard to get information. Eventually I got in touch with a guy whose speciality is that time period, and he was really helpful in supplying some of the samples we used.

Mateo: We didn’t know anything about that period. Colombia is difficult in that sense because there is no documentation at all. For the visual part, I had to look in the libraries for old papers and news from that time, and the quality of those photos are not good because they are photocopies of the original papers. In the end I had to incorporate that aspect, and it became the aesthetic of the work.

Did you manage to get your hands on original shellacs or 78s?

Mario: For the music, I couldn’t get hold of anything pre-1930s. The records from the 10s and 20s are just too scarce. Therefore I had to use whatever had already been digitized – most of which was converted really badly. I found it really interesting from the historical perspective to see who were the people making the recordings, what was the process, and how the equipment got to Colombia.

The first recordings were via Colombian composers who went to Camden in New Jersey to record there. They were called the International Orchestra, and they played compositions from all over the Americas. Later, there was a portable machine that was brought to Bogotá in 1913, and we found out that with this machine 60 songs were recorded. We could only get hold of five or six of them, the rest are completely lost. We only know there are 60 because of the catalogues from Brunswick and Victor, compiled in the 1970s and 80s. And what Colombian composers were recording at the time were basically styles from the interior of the country such as bambuco or pasillo from Bogotá and Medellin – there were not too many coastal sounds.

The composers who went to New York were recording popular music – bambucos, pasillo styles and their own compositions but played in an orchestral setting, arranged for violins and clarinets. These were very controlled ensembles, so not really folky, but more classical sounding, but keeping a rhythmical and melodic folkloric style.

Mateo: In that time in Colombia (as elsewhere) there was a big divide between the popular music and academic music; academic music was perceived as being sophisticate, and the folk music was seen as something for poor people. In Bogotá they wanted to take this folk music and reinterpret it in a way that would appeal to the elites.

How far back into the past did the research actually take you?

Mario: As we started researching we realized you keep having to going back - we thought it was all about the 20s, but realised we had to go back 40 years earlier, and we ended up finding things from the independence of Colombia. Of course no recorded music, but how the folk styles became important for the nation building concept. For example, the bambuco, once the national style, actually originated in the black communities of the south of the country, and was related to the independence guerrillas and the fight between the Spanish and the Creoles. The Creoles in Colombia are the descendants of Spanish but who five generations later don’t consider themselves Spanish anymore. So when they were fighting the music that was accompanying those battles on the Creole side was bambuco – it was a kind of resistance music.

The battles were won and slowly this music went up country, and settled in Bogotá, the new capitol, becoming the music of the new government. It became this institutionalized, elitist thing, yet it has those roots. We found some articles from around 1900 about people being shocked to find that researchers were saying this music went back to African roots, because this was already 100 years later and the music was very elegant and listened to in polite society which didn't want to acknowledge the true origins of the music.

Mateo: At the same time there was a group of people interested in popular music, but the way the saw the popular music was in a very exoticsied way. They couldn't travel to the Amazon river to see what the Indians were playing, so they imagined how it was there and invented something from that.

Do you see a parallel there in the way music is recontextualised with some of your projects?

Mario: It’s a good way to relate it to the present; now we are using this kind of European technology – computers and software – so it’s always been for us a conceptual fight between local and global, and that's something that has happened for the last three, four hundred years. And sometimes we tend to forget that it goes way back.

100 years ago it was about using violins and clarinets to give the music that sophistication, and we are trying to give it a new take – not necessarily sophistication in the sense of validating the style – but using the tools that would not have been possible then.

Mateo: I was really interested in the graphic style of the time, and how they used the instruments to create them. I found this jounal from 1907, the first cultural magazine from Bogotá called Colombia Artistica, and the graphics are beautiful, all done by wood carving, etching with bright colors etc. I wanted to recreate that in a modern way with my computer.

For us, with Frente Cumbiero and Ondatropica, these are more like tropical styles, for people to dance to, so we are always used to being in the party and making people dance. For this project we had to take a different approach, and focus on other things; we don't need to make people dance, but have a context for the sounds and visuals to mix. What we learned is that some of these styles do have a lot of potential to be reinterpreted in a dance-orientated way, so maybe we can take that a step further.

Did you feel an obligation to accurately document the results of your research, or was it purely an artistic endeavour?

Mario: It was kind of an open interpretation; we didn't try to be 100% historically accurate. Music wise, I was doing some mixing of things that didn't happen in real life, mixing time signatures and mixing instruments as well, like the bambuco from Bogotá and Medellin became very much a string ensemble, with the guitar and bandola to which I added a cello.

There weren’t really any ensembles of percussions, like African drums recorded with other instruments, so I mixed those things together to create a false folklore. In this case I took the clave pattern as the rhythmic template, and added sounds to create a style that wasn't actually recorded at the time.

As the idea with the piece centered on sounds from the 1910s and 20s, some sources came from 100 year old 78rpm shellac records. This lo-fi quality of the samples was something we had to work with. The recordings were super noisy, full of crackling and static and digitized in all sorts of ways, from high quality transfers made at collectors’ houses to terrible MP3s dug up from the internet. All of them had naturally a lot of cracks, pops, and hiss. So the use of EQs was the first stage in trying to bring out the best of the sound spectrum. I used the EQ Eight, manually setting all parameters to achieve the best result. Sometimes the idea mutated completely after the new EQ revealed a new aspect of the sample. Also, the recordings were in mono, recorded with one mic for the whole band, so we often chose to use just the beginning of the song, or the part in the middle where they stop and then start again.

About rhythm: In Colombian music there is a widespread use of 6/8 meter. Some of the early songs from 1910s lacked strong percussion since the music was mainly played by plucked string ensembles. Therefore, I used later samples from the 60s to reinforce the rhythmic structure, adapting from styles which, because of racial and social divides, weren’t recorded in the early decades of the 20th century.

Mateo: For the visuals, it was very hard to find material; there was only one film production in Colombia during that time, and they do some movies and some documentaries about Bogotá. The main work was a collage of photographs, animating these photographs, drawings and film, and I mixed everything.

It seems there’s a generation of young musicians and artists interested in exploring their cultural heritage in Latin America right now.

Mario: For us it has to do with this new musical scene in Bogotá, which groups like Meridian Brothers, are part of – a circle of maybe 100 musicians, 20 different bands on the underground scene reinterpreting the folkloric sounds, and trying to find new approaches into cumbia, courau, porro, bambuco, pasillo and a whole bunch of styles that were overlooked for some generations - at least by the generation before us who were only into rock. And coming from a kind of rock background ourselves, we have been trying to develop a new sound that has become known outside of Bogotá and in the world, thanks to the internet.

It’s nice to see how being on the alternative side of the music business gives you much more space to connect with other times and other people. I think that what we do is totally related to what happened 50 years ago, and what will happen in 50 years from now. But now that we are in touch with what was happening 100 years ago through this project, we can see that it's also related to us, it’s just that we have been out of touch with that kind of history. It’s all about history!