Kyoka - photo © Alberti Novelli

Sometimes it seems that in order to be heard in the increasingly crowded field of electronic music, one needs – besides artistry and skills – superpowers. Apparently, Japanese musician/composer Kyoka has them; is (Is Superpowered) is her first full-length album, released on the well-established Berlin label Raster-Noton. The album’s twelve powerful, gratifyingly unpolished tracks are a daring fusion of rolling beats and organic, chopped-up vocals that don’t fit neatly into any genre category. In our interview Kyoka explains how she thinks and feels about her music and describes the techniques that went into the making of her album.

Your music sounds quite fresh and playful. How and when did you get started?

Pretty early. My father gave me my first piano lesson when I was about three or four and I persevered until I was 13. I didn’t become a gifted pianist but I did learn some music theory and how to read notation.

You say you “persevered”. Were piano lessons such an ordeal for you?

Yes, they were (laughs). I always wanted to improvise but I was never allowed to. These classical lessons were too narrow for me, too constrained by rules. I absolutely wanted to make music, but with more freedom.

How did you find this freedom?

My first experiment was my parents’ tape recorder; when it stopped working one day I was allowed to have it. I took it apart right away but I wasn’t able to repair it. I did manage to manually turn the reels however and this produced some pretty strange sounds. I was fascinated.

But you couldn’t record this without a second tape recorder...

Exactly. Eventually, I even had three tape recorders. I would record on two of them simultaneously, then play them both back and record on a third machine. When the players were approximately at the same speed this would produce phasing effects. But one could also offset them rhythmically to get echo effects. That’s how I started making music at the age of seven or so, with these endless ping-pong recording sessions.

Did you study music later on?

I wanted to but my parents didn’t allow it. I studied economics for which I moved to Tokyo. I bought a Roland MC-505 Groovebox and learned beat programming and step sequencing. I recorded some demos and eventually I got mail from the Onpa label where I released my first EPs.

When did you start working with music software?

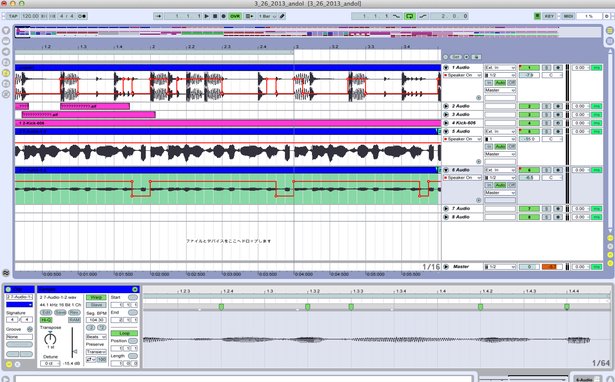

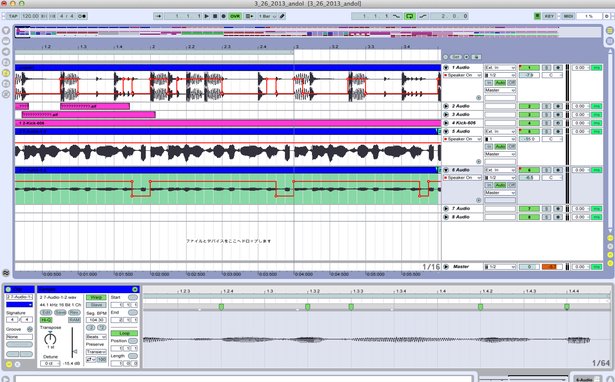

In the last year of my studies there was no compulsory attendance so I travelled a lot – to Spain, Paris, London, the States. I met a lot of musicians who were just starting off with Cakewalk Sonar on PCs. So I did that too. In 2006, in the course of a particular project, I got to know Ableton Live and started using it more and more. Now, Live has long since become my creative tool; I start every track there because I just find it inspiring. Up until about a year ago I used to often mix in Apple Logic, but now my productions are made completely in Live, including the final mix.

A lot of your sounds sound like field recordings – not only the textures but also many of the elements in your beats.

Yes, it’s true, I love field recordings. A self-recorded sound is always unique, always special. Besides, field recordings always bring their own spatiality. A kick drum taken from a sound library is always right in the middle of the stereo field. But when I record a sound in stereo that I end up using as a kick drum, I find that the kick sits better in space, it sounds three-dimensional and tangible.

How and where do you make your field recordings?

I already have a large collection, but I still record sounds when I travel and actually, just about everywhere. A few years ago, around 2008, I got very serious about it. I bought an expensive recorder and recorded everything in 96 kHz. I wanted to have the best possible audio quality for my recordings. More recently, I’ve come back to using smaller field recorders from Roland/Edirol or Zoom because I can always have them on me. I have realized that the magic of a good sound cannot be forced. It’s a matter of chance. You don’t need the most expensive device, you just need to be in the right place at the right time to press the record button.

Are there any specific microphones or techniques that you like to use?

I use simple piezo microphones that I attach to a table or an object. I knock on the object or touch the piezos directly with my fingers and then send that signal through effects. I do this not only on stage but also when I’m producing in the studio. For instance, that’s how the track “Piezo Version Vision” from the album came about.

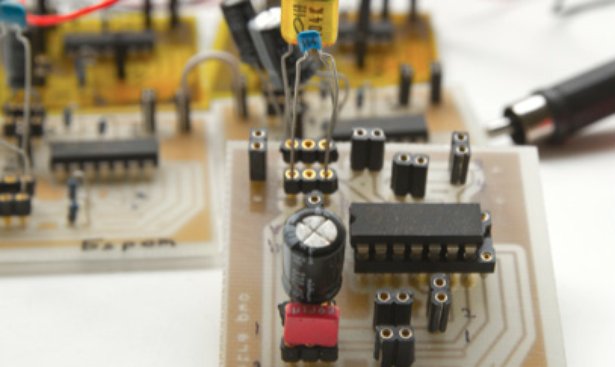

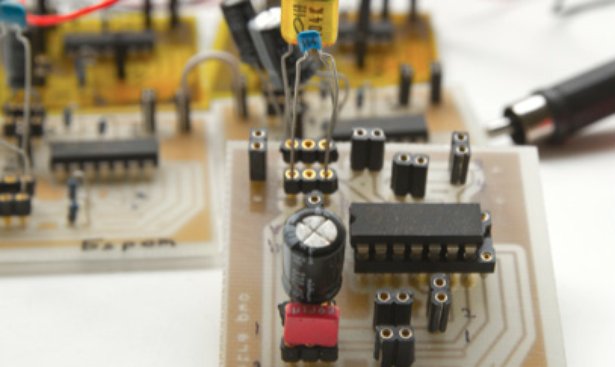

Kyoka’s ingredients for the raw drum sounds in “Piezo Version Vision”: a piezo microphone with hardware effects such as Akai Head Rush and Oto Biscuit.

How do you get the sounds you’ve recorded into your Ableton Live arrangement?

I used to drop the sounds directly into audio tracks and edit them there. Nowadays, I often put them into Live’s Sampler. I loop the sounds, maybe apply a little EQ, but usually no more than that. I want to retain the inherent magic that the field recordings have.

What kinds of synth sounds do you use?

It varies, but I definitely do love pulse waves. A friend of mine built a pulse wave oscillator for me, actually two of them. They’re hand-soldered circuit boards with batteries. I can connect them in such a way that they modulate each other. Basically, it’s a modular synthesizer, but maybe the smallest in the world! (laughs)

You definitely seem to be a fan of individualized sound tools.

Oh yes, definitely. They’re better for my adrenalin levels. When something is too straightforward, too predictable, I get bored very quickly and lose my concentration. “Proper” synthesizers are therefore not really my thing. I need more raw, unprocessed tools. I use the small pulse wave circuit boards on stage, they have no presets but instead they produce new, unpredictable sounds every time. In performance, I’m forced to react to the sounds they make and I really like this challenge.

Unconventional audio tools: hand-soldered pulse wave oscillators that can be interconnected – built by Akitoshi Honda.

Speaking of software synths and effects, the analogy to your hand-made oscillators would be something like custom-made Max for Live devices.

Exactly. Naturally, I use standard software effects such as Live’s internal EQs and dynamics effects, but in the track “Lined Up” for example, you can hear a Max patch that my friend Hisaki Ito built: a simple pulse wave synthesizer.

Your vocals play a central role in your music although they never appear as conventional singing, but are always chopped up in different ways. How do the vocals come about?

When the basic arrangement of a track is finished, I sing over it and record. I don’t write lyrics when I do this, instead I do a kind of Dada singing; whatever words and syllables come to me in the moment. This way I can improvise more freely and come up with new musical ideas for the track. I don’t like pathos and I want my music to be as pure and unemotional as possible. That’s why I never leave the vocals untouched but instead cut them up into segments, move them around, reorder and loop them.

Do you use Live’s Sampler to improvise with these cut-up segments of vocals?

No, I cut up, rearrange and copy the vocal tracks directly in the Arrangement View. This aspect of my work is more about precision than about spontaneity. At this stage I want to make conscious decisions and prefer to work step-by-step with the mouse rather than in real time.

Do you treat the vocal slices with effects?

I often apply different EQ settings to each vocal slice, but usually no more than that. However, what I really like doing is copying identical vocals slices onto two tracks and then transposing one of them in Live’s Clip View. Transposing a whole octave up or down sound pretty weird – I like that. Transposition of a half-step produces a chorus effect, which shifts over time. I usually prefer this over a normal chorus effect.

Kyoka likes to copy her vocals onto two tracks in order to transpose one of them. The chorus-like vocal sound in the track “Meander” is a good example of this technique.

Do you sing when you are on stage? You could chop up your vocals live.

No, not yet. My label and my producers think I should but I don’t know yet if that’s really going to happen. I don’t like singing women on stage, for me, that’s just too much of a cliché. But who knows, maybe one day I’ll strap a contact mic to my throat and do something interesting with that...

Kyoka during the making of IS with producers Robert Lippok (left) and Frank Bretschnieder (right). (Photo: © Sylvia Steinhäuser)