F.X.Randomiz: Stockhausen, Push and the Cybernetic Code

The aura that surrounds Karlheinz Stockhausen is tempered in roughly equal measure by admiration and misunderstanding. However controversial he may have been at times, Stockhausen’s groundbreaking electronic compositions, gigantic opera cycles, orchestral, choral and instrumental works, as well as his contributions to the theoretical understanding of electronic music, spatialization of sound, and aleatoric composition have all had some direct or indirect influence on both ‘avant-garde’ and popular music music in the second half of the 20th century.

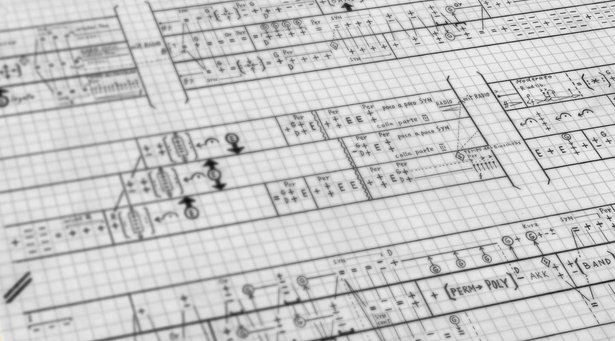

Stockhausen’s vast and varied oeuvre contains works that are performed relatively frequently, others which depend on the availability of helicopters, and others which are deemed to be so technically demanding as to be practically unplayable. One such piece – “Expo für 3” – was only performed in its entirety forty-three years after it was written. The challenge of transforming the dense, graphically notated ‘cybernetic’ score of “Expo für 3” into engaging music was taken up by sound artist and longtime Mouse on Mars associate F.X.Randomiz, vocalist Natascha Nikeprelevic and vocalist and Stockhausen compatriot Michael Vetter. The trio rehearsed and fine-tuned their approach to “Expo für 3” for a full two years before premiering and subsequently recording the work for the official Stockhausen-Verlag record label.

We talked to F.X.Randomiz about how he used Push and Live to realize “Expo für 3” and how the three musicians managed to calibrate the interplay between electronic and organic elements, and balance extreme forms of improvisation with faithfulness to Stockhausen’s score.

What is it exactly about the composition “Expo für 3” that makes it so difficult to play?

Since it was written in 1970, “Expo für 3” has never been performed in its entirety – it was considered to be unplayable on account of the highly unusual way it was notated. This notation is what can be called a ‘cybernetic score’: that means that instead of fixed tones, durations, melodies and rhythms, the score only tells the player in which direction to proceed. The piece is conceived for players who are capable of reacting to a musical flow that is constantly changing – not least of all because the random shortwave radio signals which are periodically introduced into the piece force the players into new directions. So, probably because of this special combination of improvisation on the one hand and strict adherence to a score on the other, nobody has attempted this high-wire act for the past forty years.

So how did the idea for you to try to perform “Expo für 3” come about?

That I was able to take part in the world premiere, and subsequent recording of a work for which the score looks more like hieroglyphics than music is due to the fact that Michael Vetter was a member of our trio. He’d worked with Stockhausen since the 1960s as a musician and performer, and he was considered the absolute authority on the so-called cybernetic scores. Essentially, Stockhausen and Michael Vetter (later on also Natascha Nikeprelevic) were the only people who knew how to read them. Michael played the world premiere of the solo piece “Spiral” in 1970 at the World’s Fair in Osaka and recorded it for CD in 1996 under the supervision of Stockhausen himself. Then he and Natascha Nikeprelevic performed the duo piece “Pole” for the first time in 2008 and recorded the CD for the Stockhausen Verlag in 2012. It was natural to try to complete the trilogy of cybernetic compositions with the trio piece “Expo”. And in this case the two vocalists wanted to expand their sound palette with electronics.

Did you have any musical training that prepared you for this project?

I’d say that my self-taught knowledge of electronic instruments and sound processing was more useful here than my classical piano training. It probably didn’t hurt that I’ve read a score or two, and had some experience in the world of so-called ‘art music’ – often as a listener and occasionally as a performer. For “Expo für 3”, I specifically wanted to work with an instrument that would require me to play in new ways and help me avoid relying on techniques and habits that I had internalized over the years.

Can you explain some of the symbols in the cybernetic score for “Expo für 3”?

What you see first are the plus and minus symbols, a maximum of four of these per time-event. The plus and minus symbols are assigned to the parameters of intensity (loudness), register (pitch), length (duration) and segmentation (number of rhythmic divisions). Which of these four parameters the plus or minus applies to is only indicated in a few places. This means that if just one plus or minus symbol is notated, then I am free to choose which parameter to apply it to. But I also have to be aware of the consequences my decision will have, both for myself and for the other players, otherwise we can quickly find ourselves in pretty extreme territories that are hard to get out of.

Along with many others, there are special signs that indicate expansion or compression: either an expansion in two directions from a central point, or compression of two extremes down to a median value. Perhaps the easiest way to understand this is with the example of pitch: with compression, high pitches are lowered and simultaneously low pitches are raised. Now, this same principle must be applied to all the other parameters. At the same time as the pitches converge in the middle, quiet tones have to become louder, long tones have to become shorter, multi-segmented tones have to become condensed, etc. Internalizing this way of playing demands extreme concentration and above all lots of practice – there is no time to think about what the symbols mean when you are improvising and reacting to the other players and to radio signals.

There are other symbols that denote even more abstract instructions, for example: “Play the figure repeatedly until exhaustion”. There are also a number of symbols that instruct how one is to react to the other players at certain points.

In the studio with the “Expo für 3” score, Push and a shortwave radio.

As the non-vocalist of the trio, how did you approach this piece from a technical standpoint and how did you end up using Live and Push?

Because the score provides directions but no absolute values, it seemed to make sense to give over some of the interpretive work to a computer – specifically a Max/MSP patch that could be used to follow the structure of the score. However, it quickly became clear that this sort of system was much too rigid and inflexible to use for improvising with the two vocalists. Another thing I tried was to use only strongly modified vocal samples, believing that in this way I could somehow connect the vocal and electronic elements of the piece. This quickly revealed itself to be too dogmatic an approach.

What became obvious during the rehearsal process was that, for every single sound event that the piece calls for, I needed to prepare sounds that contained parameters which could be precisely adjusted to that event’s specific character and requirements. And because I wanted to experiment with loops and sequences along with single sounds, it became clear that Live was the best solution for the task. Using Instrument Racks with Macro Controls that can have multiple assignments and individually fine-tunable parameter ranges turned out to be the ideal way for me to take control of the complex sound changes that the piece requires.

But of course the whole thing also had to be playable in real time, and I had decided early on not to use a conventional keyboard – the risk of falling back on learned patterns of playing was too high. When we began rehearsing, Push hadn’t been released yet and I initially had a setup that was made up of a Launchpad, APC-40 and QuNeo. Then when I heard about Push it seemed to have everything I needed to perform “Expo für 3” and I wanted to try it out right away. And as soon as I got my hand on a Push I had the feeling that I was playing an instrument. Plus, I could do with Push what I needed three controllers to do previously. The best thing though, was that I could completely change the entire status of my instrument at the push of a button – not only the sounds themselves, but also in how the sounds could be played, as with the various assignable scales.

My Live Set for “Expo für 3” is such that each event or group of events in the score has its own track in Session View, with its own sound source, effects and, as needed, MIDI data. All I need to do is use the arrow keys to move to the next track and everything is right there, ready to be played. The visual feedback via the display is very useful for knowing exactly where I am in the score. I can forego using the computer’s screen entirely, and can leave the computer on the side, or even behind, the stage.

Was it always your intention to have the voices pure and untreated? When one thinks of "Gesang der Junglinge" it would seem that Stockhausen would not be opposed to manipulating the voice electronically – seeing as he was among the first composers to do so.

It’s true that the score doesn’t forbid altering the voices, and it would have seemed an obvious choice to do so. But once you’ve experienced the congenial way Michael Vetter and Natascha Nikeprelevic play together and heard the unbelievable spectrum of sounds they are capable of producing with their voices, it becomes clear that any kind of electronic treatment of their voices would be tantamount to sacrilege.

When Stockhausen produced "Gesang der Jünglinge" in the 1950s, bringing together voices and electronics was absolutely revolutionary. Today, manipulated voices are pretty much par for the course, across all genres of music: in a way, the voice has been adapted to its electronic environment.

That’s exactly why it was interesting to go in the opposite direction and try to infuse the electronically generated sounds and sequences with a voice-like organic quality. For “Expo für 3”, it was important to us that we interact with one another as musical equals. Besides, the score provides for plenty of interaction on many levels.

The same principle goes for Fu Acune – Natascha’s and my experimental pop project. In our performances I have no control over her voice, not even over the volume. If I think she’s too quiet then I have to reduce my own volume – this produces a whole different kind of dynamic. For the studio production on the other hand it was extremely complicated to edit my sounds in such a way that they too would have a similar degree of vitality and lightness of the vocal parts.

Hear and see more from Fu Acune and F.X.Randomiz and Natascha Nikeprelevic and follow the artists on Facebook. Listen to more excerpts from “Expo für 3” and many other recorded works of Karlheinz Stockhausen.