At his 2015 Loop talk, Matthew Herbert presented his manifesto for making music. As he explained, the set of rules – including the prohibition of synths, drum machines, presets, and sampling other music, for example – have guided his practice since 2005, serving to upend assumptions and help him avoid entrenched practices. He also encourages the inclusion and development of accidents – his label is called Accidental Records, after all – for a new kind of compositional liberation found within a non-traditional musical system.

Historically, self-imposed constraints have been used to shake things up in Western music since at least the 18th century’s musical dice games – the most famous of which was attributed to Mozart – in which composers literally rolled the dice to choose a predetermined option for a given measure. More recently, John Cage’s work with indeterminate music in the early 1950s – especially his chance-controlled compositions written using the ancient Chinese divination text, the I Ching – sought to remove his own taste from the music.

One of Eno and Schmidt’s Oblique Strategies cards

Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt’s 1975 Oblique Strategies were both an artist edition card set and a deck of printed commands designed to help circumvent creative blocks – appropriate for a self-professed “non-musician” who foregrounded theory over practice. Eno was also responsible for the term “generative music” which has become both more technical and refined, but started as several different tracks, with all of their various properties, looped and mixing together to create endless variations. Concept records, game pieces, even YouTube search terms can help focus an artist’s practice.

In an era where technology – freed of the conventions of tonal scale and instrumentation – makes so much sound possible, it’s easy to see how a few self-imposed constraints could help clear the way to a unique path. We spoke with five other electronic musicians to learn about their ideas and conclusions about making music according to their own rules.

Stefan Goldmann

For Industry, Stefan Goldmann used "failed sounds from obsolete synths"

With 2014’s Industry—the accompaniment to his book on presets—the German techno producer created an album not only entirely from presets, but specifically, “obscure factory presets from three obsolete 1990s Japanese workstation synths. All effects are presets, all notes are quantized and most panning is purely accidental (laid out in the presets themselves). Industry doesn’t rely on successful presets but on failed sounds of now obsolete synths – industrial assumption of where culture will go, but chose not to.” As he further explained via email: “At the time of recording the project, I wasn't able to use presets on everything. For instance, automatic mixing and mastering weren't available yet. This way, setting levels and pan positions on the mixer became the only points of individualized input. One other constraint was that I didn't compose any new material, but did preset versions of existing tracks.”

If, like Cage, Industry intended to shed personalization, there was another point Goldmann was making: “I remember a time when people were really aggressive about presets and idolized what was considered to be very individual because of the sources used or the extent of effort invested. They'd slag Avicii or David Guetta because somebody could identify the presets they used. On the other hand people would worship anybody showing off modular synth patches, field recordings, complex Max-MSP patches. Once I got hold of the synths I used in the project, I found that by using three or four presets you could get results pretty much identical to a lot of typical IDM-fare, considered to be the pinnacle of sophisticated programming. That's the thing: this is how electronic music history has always been written. The sounds of the 808, 303, M1 or DX100 were up for grabs. The first one who got a record out riding those presets or near-presets to death owned that sound in the minds of the people.

“There is an entire industry trying to tell people they need to spend money on this or that, otherwise they can't do music. Most of this doesn't hold up under close scrutiny. Culturally and socially, we are still obsessed with identifying and adoring genius as if we were in the 19th century. We are biased in giving too little credit to chance, random events, readymade finds that play a crucial role in almost any culturally relevant event. House and techno came into the world due to chance events—somebody tweaking two knobs on a 303, somebody hacking a few patterns into an interface, pushing knobs at random, until something interesting stuck.”

Benge

Benge, the British musician and synth enthusiast used his vast collection of hardware as the launching point for a 2008 concept album, 20 Systems. Using 20 different synths—each dating from a different year over a 20-year span (1968-87)—he made one track on each, explaining, “I saw it as a collaboration between me and each synth, and I really wanted the character of each one to come out.” To do that, he used only the “the specific instrument, not contaminat[ing] the sound in any way with outboard effects or processing,” although he did allow for overdubs during the recording process.

Asked about the inspiration for the project—aside from the extent of instruments at hand—he replied, “I had been making lots of albums over the years where I pretty much threw everything onto each track and the result was a lot of very complex electronic music with a lot going on. So, I first wanted to deliberately limit what I was going to use on each track to one instrument and see what happened. I had been working on several ideas and it was really good fun doing them—very liberating in a way. One of the interesting things that happened after I had finished making the album was listening back to it as a whole 60 minute piece—you can hear the gradual development of the sound of electronic instruments changing over the years. It was a happy accident really, and it showed me that if you introduce some very strict limitations on your working methods, you can come up with some very interesting results.” In fact, Benge has since returned to idea of making entire records with only a single system or instrument.

Kara-Lis Coverdale

As a composer, Coverdale has spent some effort bridging the worlds of classical and electronic music, and her 2014 album A 480 is a good example of that, and also drawing in her history with sacred music. As the Canadian musician disclosed, “A 480 was sourced entirely from one choral library which contains vocal performances from 37 different singers. I wanted a way to focus the project so I could better expose or make audible the procedures I was using to manipulate the samples. Samples with multiple sound sources can sound very impressive, especially when layered texturally to create a dense and shape-shifting arrangement, because they are confusing, disorienting, beautiful collisions. However, for A 480 I was interested in making the technique of arrangement and production more transparent, so the solo sound-source approach was a good way of going about this. At the core, you could say there was an academic question I wanted to study and answer. I’m still working on the answer.” Unlike Goldmann and Benge, Coverdale made a point of altering the limited source material she was working with.

But exploring one idea is merely one step in a bigger journey for her, and while Coverdale is less interested in self-imposed rules, she acknowledges their usefulness: “I don’t seek out rules. When I make music I don’t find I need to enforce or invent rules; it’s rather a matter of locating or defining what rules already exist. Sometimes this objective is scientific and functional (ie. there is often a particular notch-out EQ treatment required to set a soprano vocal so it soars in a full mix—this ‘law’ is an acoustic one of frequencies and behaviors of energy, and in practice circumvents choice); or as in the case of A 480, it requires that I take a step back and ask myself what parameters of limitations or self-running programs (whether musical or cultural or practical or technical) are in place that allow for this thing I have made to work? Sometimes I have enforced a rule without knowing it, so it’s important to listen or look back upon the work critically from outside myself. When I ask myself these questions or apply/remove these ‘rules,’ the objective of the music (rather than my personal objective) reveals itself more clearly. The most powerful music is made when personal and musical objectives are completely aligned. This is the ultimate challenge of a music person. Awareness of determinations in your process can help you reach the holy unity.”

Andreas Tilliander/TM404

Although perhaps best known as Mokira (one of many different projects), Tilliander’s current incarnation as TM404 is particularly interesting in that it began with a one-take/no overdubs rule using only classic Roland machines from the ‘80s. The track titles for the first TM404 album detailed exactly which machines were in use, partly because he “really did not think of an audience or listeners at all. I know it’s been said in thousands of interviews, but I did record the first TM404 album for my own amusement. I had absolutely no plans other than to explore what I could do by minimizing my setup for a while.” Tilliander did use a laptop for the second TM404 album – mostly due to convenience while traveling – and notes that, “I love having rules while producing, but the actual sound is more important than any theory.

“What I learned the most was two things: The studio IS super important. From time to time, I hear people saying that a good track can be played on any instrument. Not the kind of music I’m interested in. The sound is everything. And by building a studio with various different echoes, multi FX, shitty digital synths, fantastic analog ones and so on, you will sound like nothing else. At least compared to producers who download the same sound packs for the same soft synths everyone else uses. The second thing I learned is that you really don’t have to have too many machines in your studio. It’s better to stick to a few pieces and master them to sound the way you prefer.”

While Tilliander is a self-professed gear-nerd, it’s interesting to note that accidents have a place in his work, too: “Another composer cliché I lean on is the randomness. Not completely knowing what I do and how to program various machines is my key feature. Just trying my way in the studio until I come up with a loop or two that I think is close to what I want to do.”

Mark Fell

British artist and musician Fell is known for his work in algorithmic and generative music, both as part of the duo SND with Mathew Steel and with his own solo output and installations. Examining his own career, he clarifies over Skype, “If you limit the choices you can make, the choices you do make become more interesting. ‘I have these elements, what do I do with them?’—I guess all my work is like that. I never think, ‘Oh, I’d like to have this sound,’ and just put it in. There's always a framework or structure that I work within. There were two elements in the SND sound palette, basically the rhythmic stuff and the chord-type stuff. And [the question] was, how do those two things interact? [Fell’s solo album] Multistability really is a different response to that set of ingredients. And even the weirder stuff I do, the sound installations, it tends to be very long drawn out chordal structures with rhythmic structures around it. So essentially it's the same two ingredients that I'm still dealing with. And that's grown into what I'm doing now, which is frequency structures that don't have any temporal variation and then rhythmic structures that don't have any melodic variation. [For a piece performed with FM synthesis pioneer John Chowning in Berlin,] there was a frequency structural bit, which was spatially organized but didn't really have much dynamic temporal change. Then there was a rhythmic thing that had no spatial distribution, it was from a single speaker on stage. So it was a hemisphere of spectral material and a point of temporal material, and it was really about that relationship between the two. And that is really what all my work has become about.”

As such, Fell has based not just one project but an entire career on a simple set of ideas and their interplay. It’s not only made for compelling art, it also helped to define a signature sound. But he’s been known to work with more specific restrictions for refinement. Take, for example, his set of rules, condensed below, for Multistability, which he details in an essay for the upcoming collection Oxford Handbook On Algorithmic Music(Oxford University Press USA):

“Guideline 1: Do not use the ‘pencil tool’ to enter notes into a grid

Guideline 2: No obvious or fixed tempo or meter

Guideline 3: Limited set of objects and keep patches ‘simple’

Guideline 4: Focus on velocity, speed and length of notes as compositional parameters

Guideline 5: Synchronic use of: ‘percussion’ and ‘chord’ layers

Guideline 6: Percussion sounds [derived from a Linn LM-1 drum machine]

Guideline 7: ‘Chord’ sounds [always 4 operator frequency modulation synthesis]”

In this particular case, Fell’s manifesto came after the album itself: “I didn't set them before I did it. I realized that after I'd done it, I had those rules. In one sense, it was quite formalized and I knew what I wanted to do. But in another sense, I'd break those parameters, if I wanted to. So there's one track on Multistability that clearly has a tempo that is fixed, and there's one track that uses the pencil tool, for example. So each of the guidelines, I actually transgressed, as well.” But even allowing for wiggle room, Fell admits, “For me, it wouldn't make any sense to make an aesthetic choice that was outside of this sphere of possibilities that I've set myself. It would just be like, ‘Why? Why is that there, why have I included that?’ But it's not like I'm some super nerd who has to have a logical justification for what he's doing. It is at the end of the day about pleasure and fun and enjoyment. It's just that that's the way I get it is by thinking about the way limited elements can be recombined and the relationship between the system and the outcome.”

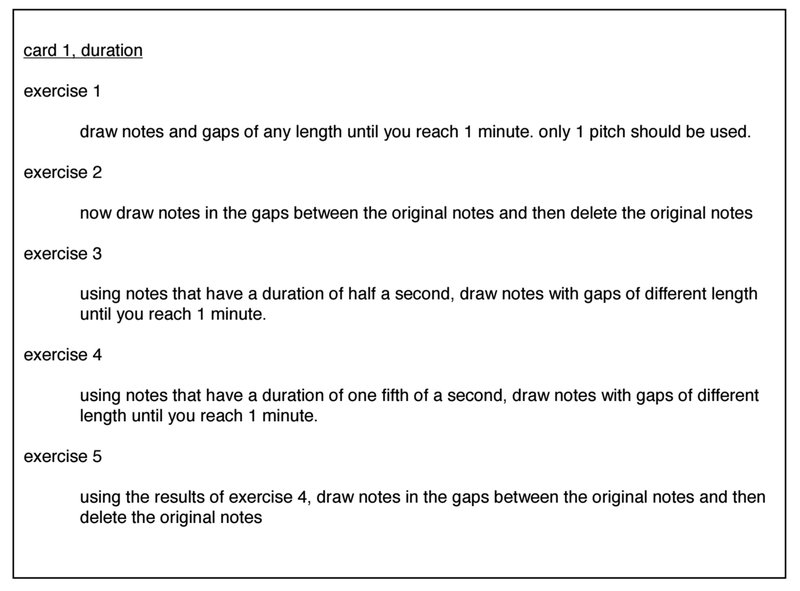

A card from Fell’s Reduced Aesthetic Workbook

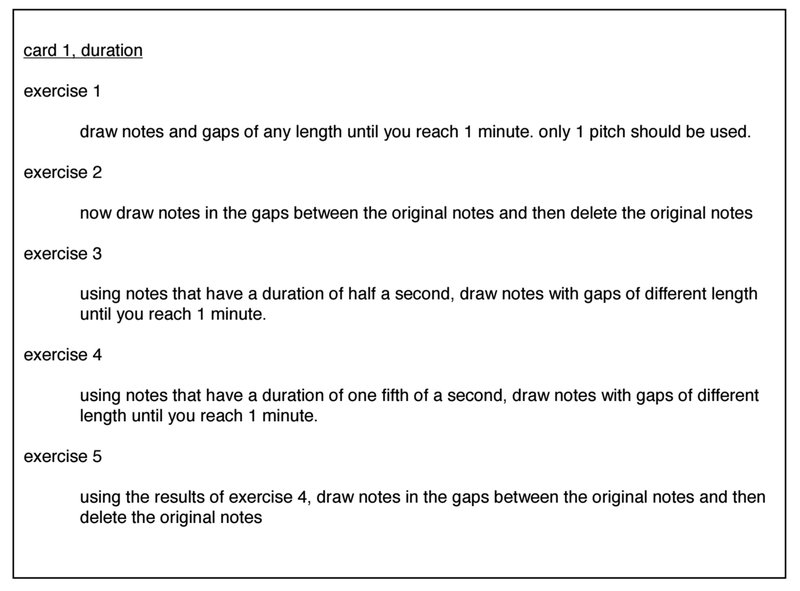

Fell continues to tinker with rules. He’s still at work at what he calls his Reduced Aesthetic Workbook. The unpublished manual consists of a set of cards – with titles such as “duration,” “velocity,” “density,” and so on – each with a list of exercises, and is specifically for computer musicians.

Words by Lisa Blanning. Read the artist interviews in full on her blog.